Top of the Pops

GM has announced that it’s investing another $7 billion to a total of $27 billion through 2025 into EVs and autonomous tech and plans to have 30 EV models by that year while shooting to make 40% of its fleet electric by that year. Brands matter a great deal. Tesla and its models came in last for consumer reliability when surveyed by Consumer Reports. The more firms spend big, the more those surveys matter. Now that state and city governments are starting to push forward to find private capital to invest into charging infrastructure — seems that even the Tennessee Valley Authority is stepping up to the plate — the next hurdle is going to be federal policy and budget support. The biggest problem rolling out electric vehicles for public transport and state procurements is that they cost a great deal more upfront to deploy, but then recoup that expense in reduced expenditures on fuel over their lifetime, differences for maintenance and repair, etc. Transitioning fuel sources entails greater sunk costs, which at least in business terms, raises the hurdle rate for the revenues that need to be realized in order to pay off financing and, eventually, turn a net profit on an acquisition. It could well be that fare hikes to support new public transit systems will be necessary in cities with less spending power, lower population density, and lower business density in city centers. There’s going to have to be a federal support facility of some kind offering ultra-low rates, grants, or something of the like to accelerate adoption outside of the biggest urban centers. Only by doing that can larger systems covering the national highway network be sustainable for any given driver’s needs.

What’s going on?

Despite numbers from the CBR showing that loans extended to SMEs picked up the pace for August-September, the sad fact is that SMEs make up only 8% of all borrowers as of the start of October even with a decline in loan refusals. SMEs already owe about 5.4 trillion rubles ($70.9 billion) in debt, but the credit impulse to save them isn’t reaching enough firms. I suspect it’s primarily about demand shock. Industrial output, for example, may be recovering, but it’s got a very weak growth trajectory to get back to pre-COVID levels and no evidence of dynamism. Russia’s 2Q overperformance compared to European peers disappeared in 3Q as any lift from external demand vanished and Russian support measures have failed to maintain income levels. Add that pensions are facing long-term decline to support an aging population, not only in its retirement, but in its ability to consume and potential drain on resources from family members to provide a basic quality of life and it’s a nasty brew for SMEs looking to last.

The latest report on the regions from AKRA shows a dire picture compared to the oil and sanctions shock in 2015. There are significantly more regions this time with industrial output levels down 15+% compared to pre-shock levels:

Worse still is that the number of unemployed Russians receiving benefits of some kind began to decline by the end of August. The number of unemployed people outnumber vacancies 2 to 1, and vacancies are on the rise too. National numbers put real income declines at 7.7% for 2Q during the worst of the crisis, but it was 12-17% in some regions. Consumer demand was still down over 12% year-on-year in September across regions. Regional inequality is going to be a significant pressure point politically and economically in 2021 and beyond.

The tax service is looking to wring water from a rock by digitizing tax record keeping and notation, aiming to save businesses as much as 3.5 trillion rubles ($46 billion) within a few years’ time. Estimates say that were the change to take effect today, it’d add 1.34% to GDP by 2024. The new system would make all records immediately transparent, lower administrative costs, and also strengthen federal authorities’ control over businesses. It’s a perfect administrative reform befitting Mishustin’s remit to save around the edges by improving state mechanisms to raise more capital for business investment. There’s more to the plan, but the meat of it lies in changing nothing structurally about the economy but mobilizing more money that the state doesn’t have to spend to improve output. It’s going to yield results, but if the business climate doesn’t get better and too few SMEs are left standing, where’s the money actually going to be invested?

The ongoing economic crisis in Russia has forced banks to accept that their margins are coming down, especially with the Central Bank holding the key rate lower, and they’re going to have to scrap for every customer. Thankfully, there aren’t any signs of liquidity stress or anything approaching the shock that triggered the banking crisis in 2015 ripping out from the oil shock. But because of inflation levels and the structure of Russia’s economic response to the crisis, it seems that the banking sector can’t turn that great a profit if the key rate heads lower. In other words, the rate level at which bank sector liquidity is threatened by the cheapness of credit is much higher, no doubt worsened by lost dollar and euro export revenues thanks to this year’s oil shock. That’s not news, but it’s telling that banks are now making sure the press know where they stand for 2021.

COVID Status Report

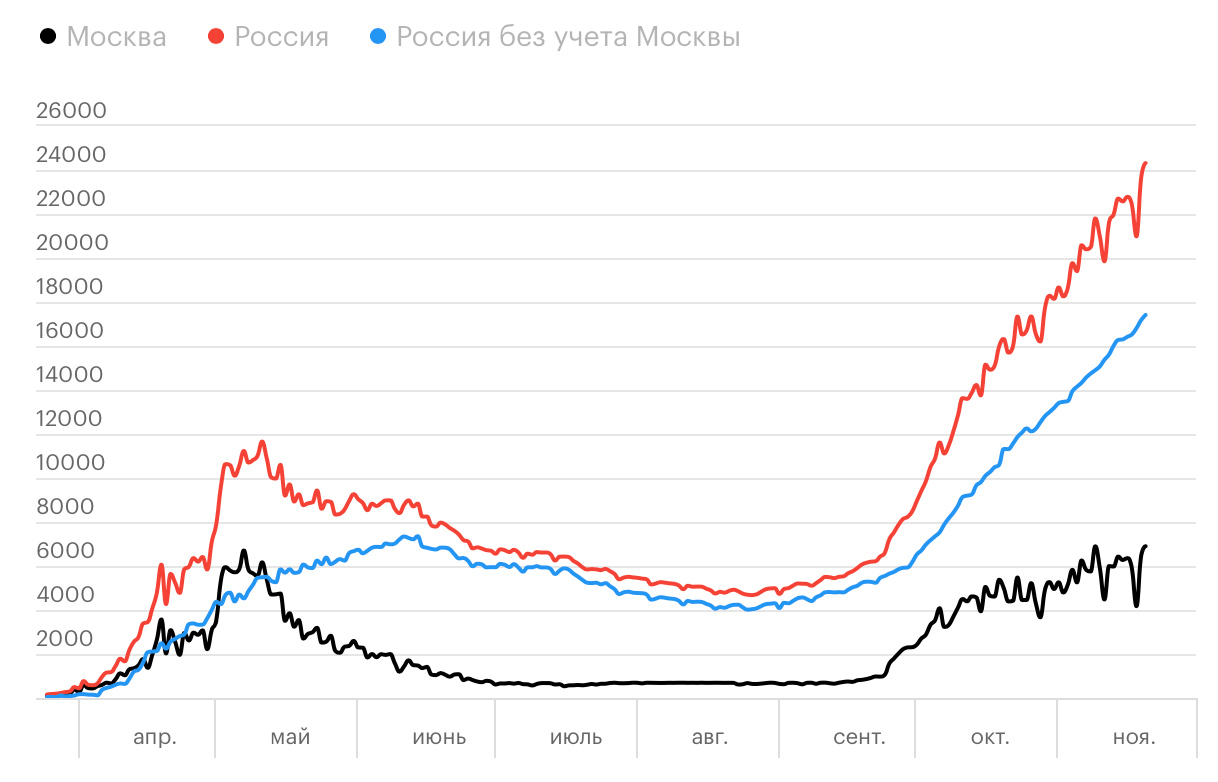

Daily cases are now above the 24,000 threshold as the recent dip in Moscow hasn’t stuck:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

Rospotrebnadzor’s Anna Popova admitted that things were worsening on TV yesterday evening, but noted that there’s been no explosion of cases in the regions. Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin is messaging to his constituents that “victory is near” and things are getting better, like being able to be seen for medical care closer to home. Seems that Perm’ and Voronezh are in the lead for worst infection rates among the 2nd and 3rd tier cities across the regions. Nothing approaching an all-of-government messaging strategy, let alone public healthy policy is evident trawling for headlines. Levada polling from early November founds that only 27% of respondents fully believe the official stats and 62% are worried, at some level, about getting infection. That’s higher than the one-third of respondents offering a worried response to VTsIOM in early October. The move towards a mask mandate is surely helping, but there seems to be more concern during this wave than the first, likely also a reflection of uncertainty over social support.

Impulse Control

The Central Bank’s most recent monitoring of financial flows provides some useful snapshots for the extent of the impact of the economic crisis on financial flows within the economy. The following is a graph depicting deviations from the “normal” 4-week moving average for financial flows from the oil & gas sector and non-oil & gas sectors based on gross value added. Purple is total gross value added and gray excludes oil & gas as well as state administration and spending:

Gross value added is a measure of how much of a firm or sector’s contribution to GDP since it’s calculated by taking a firm or sector’s gross output and subtracting intermediate consumption i.e. the things it consumes to make whatever it makes.

GVA = gross output - intermediate consumption

The chart above shows that the OPEC+ production cuts are impose a drag as large as -7% at points this year, but now only seem to be holding net financial flows of payments back about 2-3% as the economy stabilized to the new normal (within limits) and the 4-week moving average smoothed out and state spending is producing around a 1.1% bump for GVA if it’s included. In other words, the economy has only just come close to fully adapting to losses of payments from the cuts. But the fallout could be much worse than it may first appear here.

Breaking down sectors further, CBR reporting shows that activity for architectural and technical project development and management is still down 36-37% while the sectors showing growth are led by pharmaceuticals, medical care, and property. Businesses aren’t expanding or breaking ground while consumers scramble to sink their savings into a better vehicle than bank deposits or equities and make sure they get treated. The cuts and low gas prices are a bit more interesting to examine against past years when it comes to the pattern of incoming payments for the financial system. These are fixed against 100 as the normal level. Left is cash inflow, right is cash outflow for 7-day moving averages:

As you can see, oil & gas produce inflows of capital (in foreign currencies) that go in peaks and troughs. Neither oil nor gas are getting close to their normal peaks in while outflows kept relative pace, held down by cuts. The dead space for oil in August had a lagging effect whereby about 6 weeks later, banks faced a liquidity crunch that the Central Bank handled. The cyclical chart is useful, I think, for reflecting the problem oil & gas could well have going forward if prices remain lower. Even with some now auguring a return to a tight oil market by midyear 2021 as the contango spread for oil futures falls low enough to not cover the cost of transportation and storage, there’s the pricing problem since US shale hasn't gone up in smoke yet.

I’d need to run a real analysis on this, and should do at some point in the near future, but it’s my bet that these inflow cycles we see correlate heavily to concerns about foreign currency liquidity for banks on a few week lag, which by extension ripples out through borrowing rates in rubles for SMEs and larger firms since ruble reserves would be exchanged for foreign currency. That means that credit impulses meant to promote consumer demand face some constraints, if not significant ones, depending on how oil prices get next year with this bi-weekly cycle of cash in and cash out. But the relative cost of cutting production would appear to be higher than macro indicators elsewhere suggest given the relative strength of outflows from the sector vs. inflows.

The 1.1% of GDP figure from CBR calculations tracks with social transfers and the comparison between oil & gas revenues this year and budget obligations:

I still wonder, however, if that fully covers the ripple effects of procurements given that with planning on things like office and building construction apparently down while MinFin aimed to “stimulate” the economy by not cutting spending (a stupid trick), those procurement contracts have to be filled to spend the money appropriated. Money that’s been appropriated but goes unspent is criminal during a crisis like this. Metals and other extractives show steady performance this year against past years:

First metals:

Then ‘other’ resources:

That other category is fascinating, and could well be because of past investments into production that have now borne fruit. Either way, these graphs don’t show scale of volumes, but intensity of variation. To maintain the credit cycle as is in Russia without a change in macroeconomic policy from Russia’s main institutional players, there’ll have to be a rise in foreign currency earnings from these two sectors to help offset losses from oil & gas, and thus keep lending at Russian banks lower by maintaining foreign currency liquidity. The second axis is a bit wonky, but in a pinch, was the easiest way to include a % change visual pulled from the CBR overview of the external sector:

My wager is that oil price recovery, at best, returns the 2020 numbers to 2019 levels, which would ease things for credit expansion. But the more that net changes in reserve assets accumulate and aren’t used to underpin fiscal policy, the more drag there’ll be on lending since borrowers will face an economy unnecessarily starved of demand. Mind you that such a recovery assumes oil returning to an equilibrium around $60 a barrel. I think $50 a barrel is much likelier and more reasonable as a gut check and based on underlying supply and demand, which would mean recovering roughly half of the difference. That means more pressure on the current account, which based on the structure of the Russian economy, ends up being less demand and less growth unless the Central Bank is willing to jettison orthodox. The key rate’s just .25% above the inflation target and inflation doesn’t appear to be driven by monetary factors right now.

At the same time that you can trace credit impulses in Russia, if indirectly (and note that I’ve used stuff new and readily in hand, not necessarily the best proxies), credit cycles elsewhere weigh heavily on the price outlook for oil & gas, and therefore the relationship between Russia’s current account surplus and its banking sector’s liquidity and ability to sustain the current credit expansion. In the US, all signs point to an impending cliff since the knights of the working class in the Democratic Party couldn’t be bothered to at least agree to a skinny bill back in the September-October negotiating rounds and, one assumes, are still insisting on liability claims and worker protections related to COVID rather than focusing on the real protection from COVID: being able to afford not to work. Republicans, of course, are up to their usual “let them die” Marie Antoinette routine:

At the same time, markets have been spooked by recent bond defaults from state-backed firms in China. Presumably Chinese authorities might consider allowing defaults to rise in order to weed out the worst-performing firms, but doing so risks exposing just how much unsecured debt and false advertising and accounting are used to generate market trust in the country’s firms via politically-influenced ratings agencies. While not a default risk, it’s not like Beijing has a firm grasp on loose credit given that it turned to a credit expansion to back it supply-side response without spending as much money directly. When US consumers run out of money to buy Chinese exports, that’s going to ripple back into the sector that’s driven China’s recovery. And at the same time, the ECB’s Christine Lagarde is singing a song about the success of EU economic measures — a mixed bag, but certainly successful socially — while pleading for fiscal support and trying to lobby for a capital markets union. In the event that happens, well, consider even broader attempts at credit expansion while negative interest rates shred European bank profits. Russia’s credit markets are bound up in what net consumers elsewhere are doing to the price of commodities, and the current account squeeze to come is going to require a rapid deepening of domestic financial and insurance markets.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).