Top of the Pops

Oil prices are headed back to 1-year highs as OPEC+ assured the market that it’s sticking to its guns and confident that supply cuts are returning the oil market to balance. The demand scenarios they’re looking at internally are worth thinking more about:

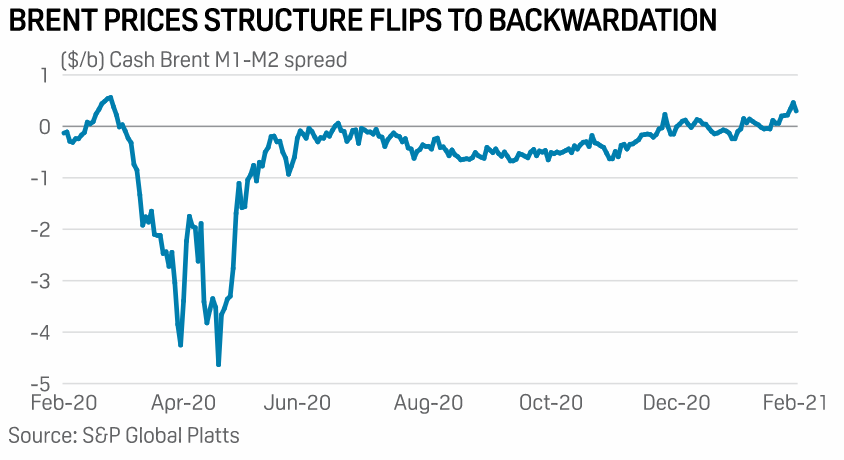

The issue isn’t demand recovery to pre-COVID levels sometime in early 2022, but rather where the supply/demand balance and prices fall. Here, the alternative scenario is really about non-OPEC+ supplies booting up, triggering market surpluses in April and December that will keep prices from breaking out of the $55-60 a barrel range for Brent crude. On the demand side, China bailed OPEC+ out last year, but rising oil prices make it less attractive for Chinese importers and refiners to fatten crude stocks at bargain deals. Brent futures contracts are also now trading in backwardation:

Basically, the market expects that the futures prices for contracts that reach maturity down the road will be cheaper than the expected future spot price. That means that the current price increases will stick and, in gradual fashion, continue based on the price curve. But there’s good reason to believe US shale supply will come back with the current price levels in a few months’ time if that keeps happening. Drilled but uncompleted wells (DUCs) are a mainstay for shale producers who preemptively drill so they can quickly ramp up (or down) production in response to short-term price fluctuations — remember that a fracked well produces most of its crude in a few weeks’ time. DUCs are now back towards pre-COVID levels as firms position themselves with the current price rally. The question is timing. If demand hasn’t recovered enough, OPEC+ has to gut out some more months of deeper cuts. If not, then it won’t, but prices will probably stick lower. Either way, any short-term relief higher prices give Russia and its budget will be just that: short-term. The structure of the oil market hasn’t changed, nor the structure of the problems facing OPEC+ and supply side management.

What’s going on?

Agricultural firms are reportedly asking that the state stop its price control policies which are cutting into profit margins and instead use subsidies to offset higher costs. Exporters are arguing that the current export duty system and price controls may ruin the national goal of $45 billion in agro-exports by 2030, threatening investment levels, long-term competitiveness, and price and production instability whenever the most direct controls are lifted. The losses are also unevenly distributed. Export controls aren’t as bad for the bottom lines of firms growing in Black Earth regions and around the Kuban’ with ready access to Black Sea ports. But attempts to expand production in the Far East and improve its own food self-sufficiency to reduce the logistical strain on the Trans-Siberian railway and trucking industries and lower consumer costs are much more seriously affected by marginal losses in profit from higher prices since their operating margins are slimmer due to worse quality land and worse infrastructure. The current process puts pressure on persistent policy aims of cultivating more land outside of European Russia.

For the first time since September, weekly data showed no inflation on a week-on-week basis. The main culprits were weak demand and a strengthening ruble:

Title: Inflation expected and observed by the population (%)

Black = annual inflation Orange = observed inflation Green = expected inflation

Part of the shift in observed and expected inflation come from a changing structure of spending. More money’s going into food — its share of consumer spending rose by 1.2% — while the share of spending on others goods and services fell 0.2% and 1% respectively. There’s evidence of deflation for prices of manufactured goods against still rising or higher food prices. Domestically-made cars got a little cheaper, for instance. But none of this is directly attributable to government price regulation polices. It’s rather a reflection of the better macro environment as import compression from 2020 has helped prop up the ruble as oil prices have risen and consumer demand is not recovering since real incomes are still down over the last year and the economy hasn’t fully re-opened. Weak demand is generally the cause of lower inflation in the Russian economy at the best of times (not sound money), and needless to say these aren’t the best of times.

A relatively minor customs declarations change reportedly only affecting about 5% of the goods crossing the border led to a flurry of problems and disruptions on Feb. 1. The short version of the declarations change is that certain types of cargoes, transport, and areas where said customs crossing is registered automatically distribute the customs declaration to appropriate authorities based on the specific good in question, its final destination, and EAEU reporting requirements. The Federal Tax Service swears that it’s just a small part of trade affected, the market’s known about the change a long time, and recent improvements in customs clearance times have made any changes feel more “sensitive". There’s just one problem, then: those changes have encouraged Russian firms to expand the use of just-in-time inventory management techniques and the Customs Service can’t really seem to justify the new system or its purpose aside from expanding surveillance of economic activity. Publicly available information was only put out at the end of December and quite lacking, it seems. Logistical holdups end up raising prices/costs, so watch this, even if it’s a relatively small part of trade affected.

VTB estimates that thanks to state anti-crisis subsidies and refinancing activity, mortgages were as much as 25% ‘better’ — more attractive on a cost/return basis — than renting. Despite a national decline in rental demand due to the outflow of migrant laborers, students, and tourists/longer-term visitors, rents only fell 3-5% nationally. But even with the housing bubble state policy created in response to COVID, the cost differential shows that buying makes a lot more sense for a lot more people. Just note that Moscow is its own animal as a housing market:

Title: Prices on housing in Moscow, (000s rubles/month)

Descending: 1-bedroom apartment, 2-bedroom apartment — Left = cost of mortgage (with 30% down payment and 19-year, 7.3% rate terms), Right = monthly rent

If the average rent for the 2-bedroom apartment comes at around 51-52,000 rubles a month, a couple or individual could reasonably get financial terms to pay about 40,000 rubles monthly on a mortgage for that same property. This gap is massive, and it goes to show that the presidential administration does not understand the economy, nor does much of the so-called ‘economic bloc’ if they didn’t realize that extending cheap credits like this when savings rates were being driven up artificially high by declines in consumer spending except on staples was a smart move (the run of net bank withdrawals in 2-3Q probably supports this reading even if savings data is weak). The other thing to consider is that the inflation data we have on hand is likely understating the inflationary effects of this policy because of the better terms available for financing despite climbing housing prices and reporting methodology. Higher housing prices will inevitably feed into construction costs, and then into other basic industrial inputs. Around we go.

COVID Status Report

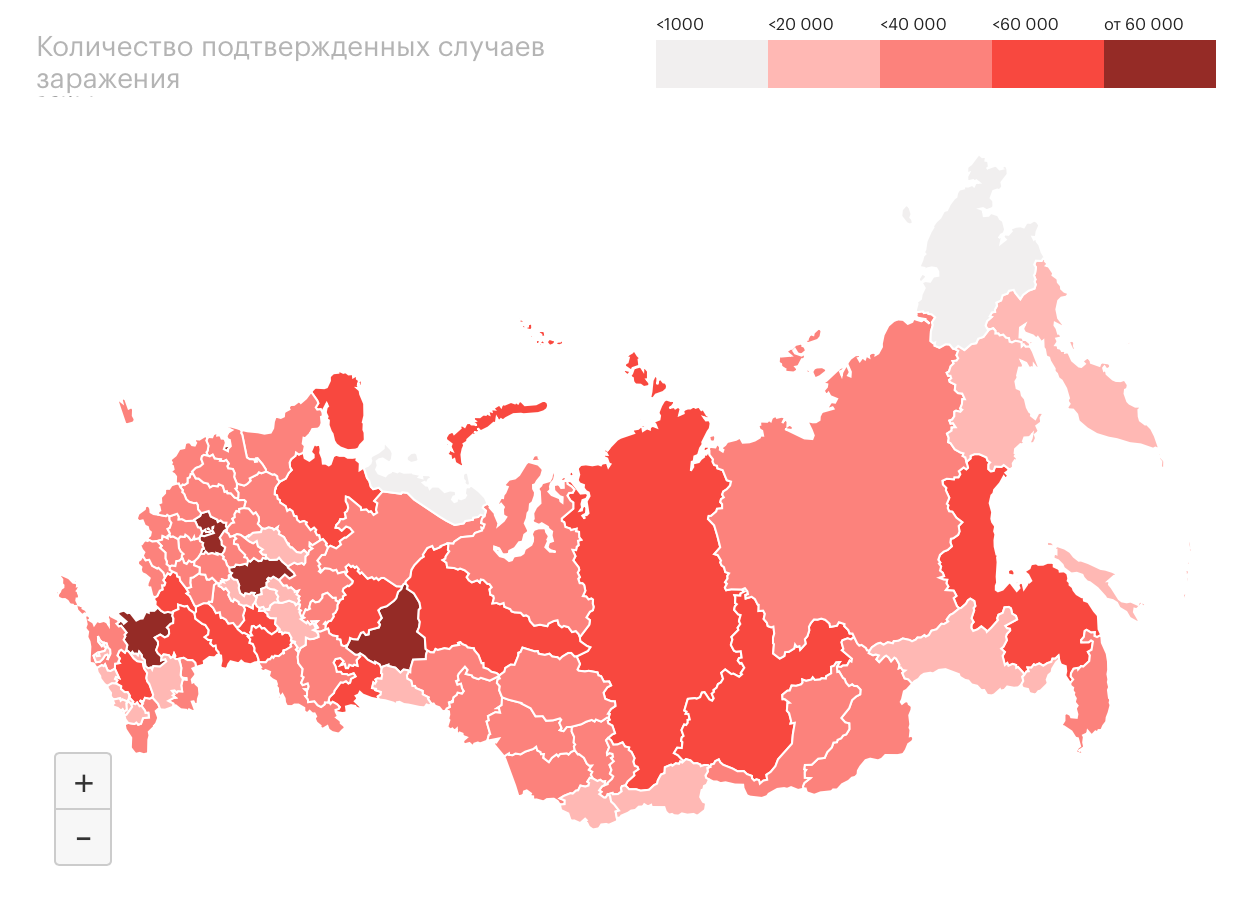

Daily cases came in at 16,714 and reported deaths at 521. The slight uptick was in Moscow, not the regions. The regional map of net cases highlights the progress made since mid-December:

The WHO is telling Russia not to let up on restrictions that prevent the spread of COVID-19 in a clear counter-messaging move against the revealed policy preference in Moscow to try and open up as soon as possible. But more importantly, the WHO declared the Lancet’s review of the Sputnik vaccine’s efficacy as proof that it works. That confers a degree of legitimacy, even if the organization’s taken a big hit from its clearly political decision-making around China and the information disseminated on initial responses to the pandemic on top of Trump’s decision to pull out. Flights to Azerbaijan and Armenia have been relaunched, which hints both at Russia’s confidence that it can support vaccination efforts in both countries as well as its ability to contain any spread in Moscow where the vast majority of the flight traffic would end up. The decline in St. Petersburg, the other major tourist destination, is also dramatic — 41% of cots in COVID hospitals are now free. What looks like progress continues.

Jolly Not-so-Green Giants

Rosneft is talking with BP about future joint green/greening projects and investments into low-carbon fuel refining and fuels and the two have signed a sustainability and carbon management collaboration agreement. It’s a logical play for BP to try and turn its 20% stake — a massive problem for increasingly eco-focused investors — into a strength. A plausible interpretation is that BP is going to try and dodge sanctions risks by focusing on green investments or else use its ownership stake to pressure Rosneft into expanding its use of renewables to power its oil fields and operations. But this seems somewhat doubtful only because Russian firms will lobby to create legal preferences for domestic firms and the localization of production, which will make any such gains for BP a lot less attractive before considering other structural impediments (which I’ll note later). Still, it’s a big signal of where western companies mostly in or adjacent to energy still interested in the Russian market may turn next: their competitive advantages building, deploying, and maintaining renewable power capacity in support of extractive operations.

It’s exceedingly difficult to see how import substitution policies that apply to an ever-broadening set of economic sectors will work fast enough if Rosneft and Russia Inc. are serious about making this pivot. One area of likelier collaboration would be nudging Rosneft’s strategy for the rollout of future LNG projects. The updated national LNG strategy through 2035 discussed by Aleksandr Novak at the end of January includes three Rosneft projects with a combined capacity of 95 million tons annually (about 129 bcm annually, which is a whopping total). An Exxon subsidiary was supposed to help Rosneft launch Far East LNG by 2027, but the company held off on market uncertainties. Unfortunately for Rosneft, Exxon just suffered its first annual loss in 40 years, wrote off over $19 billion in losses last year, and has opted to protect its dividend over its growth plans to ensure returns to investors unlike its green-leaning competitors like BP. Exxon’s such a money pit that its spent $30 billion beyond its cashflow since 2015 when the industry was supposed to be cost-cutting, right-sizing its teams and investment strategies, and high-grading its portfolios effectively. It’s hard to imagine it takes a punt on a Russian LNG project with shakier economic fundamentals and a government that loves to tinker with tax regimes and pressure foreign firms in the energy sector when it needs to.

BP, however, has a different card to play. It’s clearly winnowing down its portfolio and making sure that only the highest-earning projects remain. BP along with Siemens and Prumo just handed over shares of two LNG-to-power projects isn Brazil to SPIC Brasil. The company is raising cash by letting small and mid-sized players into its existing base of profit-generating oil and LNG projects to invest into non-oil & gas growth opportunities. It’s not inconceivable that Rosneft’s LNG plans, while of limited interest swapping equity for offtake from the LNG plant’s production or other methods, could be a chance to invest into power generation. Wood Mackenzie estimates that Asia-Pacific LNG plants could cut their emissions by 8% using green power on site rather than feedgas, freeing up more gas for LNG export or else to sell to the domestic market. That would also require a much better regulatory regime friendly to foreign investment in the power sector, which seems unlikely. But as carbon neutral LNG cargoes become commonplace on the market, even with their attendant challenges of actually tracking carbon emissions per cargo, the marginal initial capital costs of investment into renewable infrastructure on site could be outweighed by greater export earnings or domestic sales as natural gas demand has a considerably longer demand growth runway in the next decade to 15 years than oil and a long-term bifurcation between long-term contracts setting a viable price floor and spot prices fluctuating with demand.

It’s been well-documented that Rosneft’s plans to develop Arctic oil seriously challenge BP’s green plans. There’s a basic problem for any attempt to green Vostok Oil, which by all accounts would be a cluster of oilfields producing a massive amount of crude: there probably isn’t enough sun in the Arctic enough of the year, it’s more expensive to maintain solar and wind power in Arctic conditions, and the costs of repair, maintenance, and replacement are also greater due to logistics. Once again, we’re looking at a bunch of investments that will have to be supported by the state to be viable, creating a situation in which any realized investment returns necessitate losses absorbed by the consolidated budget. I'm also unsure what it is BP intends to gain from the partnership. Renewables are a lower risk, lower return business. Oil companies simply can’t maintain their profits, especially when you consider the relative cost of debt against the returns realized from investments that operate like utilities. It’s one thing to try and make this model work if you can change your business model by selling off upstream stakes or LNG plants to mid-sized operators that aren’t vertically-integrated, publicly-traded, and/or diversified while reaching agreements with them to supply X projects with green power and, perhaps, trying to recoup money via carbon emissions trading schema or price premium earnings split between the oil producer and BP realized from lower or zero emissions activities. (That was a just an off the cuff idea, the legal mechanism and acceptance of business risk in that case would be hard to imagine negotiated into a contract but it’s a possibility). It’s another to try and sell the public on a lower profit, more stable business model working with a company like Rosneft that isn’t even interested in the energy transition in practice.

Symbols do matter though. Rosneft’s agreement with BP isn’t that significant for its own operations because of the structural impediments to making it mean something substantive. It does, however, presage a shift in foreign business lobby interests on the Russian market which, in many other respects and sectors, is stagnant or else a headache to navigate and a problem derived from sanctions:

This didn’t show up great (these are all in US$ blns), but if you look at direct investment on the balance of payments data from the CBR pre-COVID, you can clearly see the impact of sanctions and the oil shock on the net position of investment into the banking sector (light green), which also appeared to recover slightly by 2019 and remain positive while net investment into the economy from abroad turned negative. Direct investment into banking sectors is a key part of the integration of financial sectors globally, hence why I pulled it since the years preceding 2014 showed this was steadily happening. BP and companies like it are able to bring about a level of financial confidence with foreign banks that Russian firms can’t achieve on their own. The same public pressures that pushed Rosneft and BP to sign this relatively toothless agreement are affecting the publicly-traded banks financing dirty industries facing a rising tide of pressure from Central Banks and financial regulators who realize that climate change poses massive prudential risks to financial systems, and that therefore we have to begin building in regulatory requirements around best practices for assessing the climate impact of businesses’ activity when trying to raise financing. And that comes on top of the greater borrowing costs Rosneft faces abroad due to the sanctions regime and reputational risks that lenders have to account for while sector-specific investments into energy are still hostage to price cycles, demand expectations, and a huge amount of uncertainty.

This one-two punch — a weak domestic business climate kills green investment interest from abroad despite competitive advantages and greater difficulty borrowing from foreign banks for joint ventures with foreign firms that prefer not to take on ruble currency risks when financing projects — means that while BP and other firms can find marginal gains on the Russian market with its oil & gas producers, it’s ultimately incumbent on Russian firms in the sector to establish better practices and lobby for better policy frameworks domestically. Russia’s failures to improve energy efficiency and green itself stem from its policy choices and political economy. Those failures offer considerable massive upside to foreign firms that are willing to take the risk. I don’t think BP is committing a lot of capex to Russian projects to make this agreement ‘real’, even if this is a leading indicator about the future of the structure of foreign investor interest in Russia and Russia’s import dependencies.

What’s more curious to consider in the next few years is if Chinese firms decide it’s worth the leap in a bid to maintain exports and industrial capacity. I have to look more into it. But that’s the new geopolitics of energy. Manufacturers who can install green capacity in support of hydrocarbon production have a lot more leverage than the producers alone if they can’t do it themselves. There’s a reason that John Kerry, Biden’s climate envoy, met with the CEO of the UAE’s Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. The US can push to help with decarbonization with Gulf partners, forcing large but more marginal producers — marginal in the sense that it is a price-taker, not a price-maker since it lacks swing capacity to vary output upwards, only downwards through restrictions — to up their game. Moscow can’t be happy about that latest turn in US policy, nor can it ignore that it has an opportunity to rebuild some of its international business relationships if it takes this opportunity seriously instead of playing it off as another excuse to hand out subsidies and rents.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).