Around the Horn

The ceasefire agreement brokered over hour talks in Moscow between the Armenian and Azerbaijani governments was, frankly, a joke. It pertained only to allowing the evacuation of the dead and wounded and providing access to the Red Cross, but was over after about 10 hours. At this stage, the EU has noted that it’s “extremely concerned”, which is its usual way of saying it will be nothing of substance to stop the conflict. Moscow appears unable to negotiate a more durable ceasefire at the moment, both Yerevan and Baku have reasons to continue escalating, and Turkey now knows that the EU is not leading any mediation process. It’s a cluster, and everyone loses, most of all those living near the LoC.

In Kyrgyzstan, it appears that the worst of all possible outcomes has taken place. President Jeenbekov has declared a state of emergency, ordered the military to restore order in Bishkek, and placed a ban on all public rallies and instituted curfews while releasing former Kyrgyz president Almazbek Atambayev from prison as well as Sadyr Japarov. Japarov was promptly named prime minister and has assured the public in interviews that Jeenbekov agreed to step down a few days after Japarov was sworn in. In a single stroke, what appeared to have the potential to be an outpouring of public pressure for change has become a game of musical chairs for elites trying to exploit the grievances of the country’s north.

In Belarus, thousands protested in Minsk against police violence used to discourage and suppress political dissent. Lukashenka even met with political prisoners being held by the KGB as a stunt, presumably aimed at trying to ameliorate some concerns with the public about their treatment and to find a way to ease protest activity. No such deal was reached, and the police used force to detain 420 protesters nationally yesterday, 300 of those in Minsk.

Finally, president Emomali Rakhmon has won re-election in Tajikistan with a pedestrian 90.9% of the vote. MTGA lives to fight another day. Expect a crazy week ahead across Eurasia.

What’s going on?

The industrial group the Community of Energy Consumers (rather arch name…) are now lobbying the government over long-term investment plans into the modernization of the nation’s power grids and power generation plants. The group refers to the Market Council’s forecast that current plans will lead to annual energy price inflation at or above 9% compared to targeted annual inflation from the Central Bank of 4%. Reforming investment into the energy grid is increasingly a pressure point for industrial and export policy.

For the 2nd day, new cases of COVID in Russia broke 13,000, nearly matching yesterday’s peak of 13,634. Other underlying data collected from the Federal and Regional Operational Staff for the Fight Against the Virus (clunky translation intentional) shows recoveries vs. deaths and the underlying trend isn’t good:

Green = recoveries (new cases) Black = deaths (new cases)

These numbers have to be watched closely depending on whatever measures are taken next, especially given the systemic risks of medical price inflation and bed shortages in Russian hospitals.

Yandex has bought 100% of the platform K50, a firm based in Skolkovo, in a move aimed square at Google. K50 focuses on improving the effectiveness of contextual advertising for businesses online. The acquisition is another example of Yandex’s success in Russia’s tech ecosystem and its increasingly strong position on the Russian market. Yandex reportedly has struggled to keep pace with Google’s success leveraging non-brand traffic for businesses. Whether it can do more internationally is the future test of its success.

Natural gas prices on the European market are ticking back up, with the TTF hub in the Netherlands registering prices above $180 per 1,000 cubic meters. The price recovery is highly seasonal since heating is obviously in much greater demand come winter, but it’s notable that prices are converging back with their year-on-year price levels from 2019. That should improve Gazprom and Novatek’s 4Q earnings, and one expects would buoy shares, though with quite limited upside given that broader energy demand is still in an odd spot and industrial output in the EU isn’t back to growth yet.

CO2 Bogus: The Crucial Conflict

Today, I wanted to reiterate some of what I’ve been thinking about and dive back into carbon taxation and the Russian economy. The “Carbon Balance of Terror” is one of the ideas animating my thinking about the next decade in business and political trends. Larry Summers coined the concept of a “financial balance of terror” within the global economy. The US had to provide external demand for production from China and the rest of the world that their own economies weren’t generating domestically, whether from “excessive” savings, suppressed demand by things like wage suppression, and other forms of economic dysfunction and rising inequality. It contributed to the financial instability that exploded in crisis in 2008.

A shift to reduce carbon emissions creates its own internal logic not that different from the balance sheet view of the global economy - that the world is stitched together by different national economic balance sheets and any given surplus or deficit must be matched by a counterpart deficit or surplus elsewhere. On its face, carbon’s different. It can keep growing endlessly (in theory) without the same types of feedback mechanisms that, say, the value of a currency holds or the management of a nation’s trade balance. However, there’s a clear point at which carbon emissions feedback into economic balance sheets, via damage and destruction to property, impacts of weather and climate on productivity, and more. We’ve crossed that threshold. Now, to consider how carbon can rattle national balance sheets as the world moves towards pricing it, if slowly.

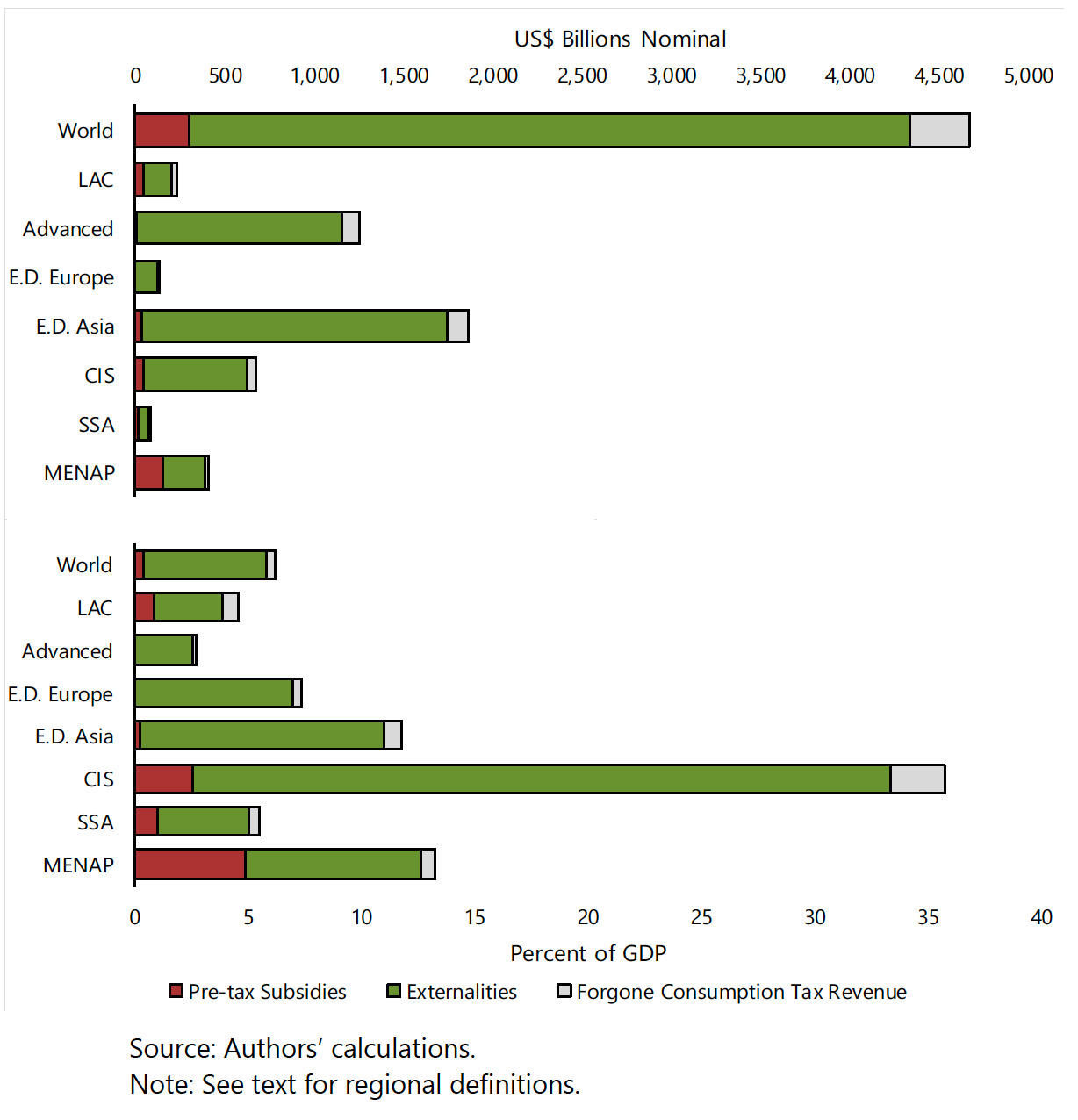

Consider these two charts from an IMF report last year estimating the significance and impact of energy subsidies:

Acknowledging that one study isn’t the final word, over $6 trillion in global output can be calculated in terms of energy subsidies. The aggregate global share breaks down starkly at the regional level based set against 2015:

There are a host of considerations worth scrutinizing when ever anyone attempts to model costs or foregone revenues on the basis of externalities, but suffice it to say that the CIS - led by Russia - is by far the worst subsidy offender in relation to GDP. Put another way, a huge portion of the national economy would be displaced if externalities like pollution were to be priced into consumption. And it’s not just about losing output from higher consumption costs. It’s also about generating tax receipts and, in effect, rents from carbon that can be redistributed and spent in such a way as to reduce both the necessity for such revenues and carbon emissions output as fast as possible. You can’t just internalize carbon costs for businesses. You need to invest and redistribute the earnings from the imposition of a tax on an externality like pollution.

Here’s another IMF take estimating % of GDP revenue earnings from a carbon tax at $35 per ton and $70 per ton across countries:

This is a snapshot that has not adjusted anything in relation to changes in output i.e. carbon tax burdens would disproportionately affect oil and gas production in a place like Siberia compared to, say, Texas or the Gulf. But these figures making totally static assumptions as if economic activity isn’t changed by carbon taxes and are applied globally and use the preceding numbers to give you an idea of the volume of fiscal revenues Russia could realize depending on how such a tax is implemented:

In current USD-ruble terms, the Ministry of Finance would have raised over 6.2 trillion rubles in 2019. Clearly, that’s not at all how that would work in practice since you’d see a large hit to GDP and domestic price inflation based on things like flaring and energy inefficiency. But it’s a lot of money, and would have huge implications for national economies, especially those whose business and lending cycle is dependent on hydrocarbon exports.

This is where the balance sheet part of the equation comes in. One country’s “surplus” in terms of its carbon tax base fast becomes a net loss for its balance of trade and, potentially, inflows of capital into things like its bond markets if other producers of the same product are able to more efficiently produce the same good with fewer emissions and, crucially, with a lower net cost once transportation is factored in. Think of the following in layman’s terms for the cost of making and shipping a thing;

Production Cost = materials + labor + ((Carbon tax coefficient)(materials+labor))

Consumer Cost = (Production Cost + shipping cost (and potentially ((carbon tax coefficient)(carbon used for shipping) + domestic taxes) * exchange rate adjustment * inflation adjustment

That’s a grossly simplified model, but it’s meant to capture the problem that there has to be a global agreement on tax with stipulated room to maneuver for countries depending on levels of development, akin to existing WTO trade regulations that allow countries differentiated space to impose tariffs and some related distortions on trade per their accession agreement and level of development. Inflation is a great example of the challenge. If a carbon tax adjusts upwards significantly in a producer country and an importer can’t readily replace that production, the increase in production cost is effectively passed on as consumer price inflation (unless a government uses a subsidy of some kind). Similarly, shifts in exchange rates affected by trade due to differential carbon costs end up hurting consumers in carbon-intensive economies reliant on consumer goods imports.

Take the recent speculation about geopolitical factors and trader sentiment driving the ruble’s value. Here’s a good chart from Kommersant today on Russia’s balance of payments (how much it consumes vs. produces domestically) and the ruble:

Title: Dynamic indicators for the balance of payments and ruble exchange rate

Blue = current account balance of payments Orange = OFZ purchases Purple = net private sector operations Green = currency intervention Black line = ruble/US$

Shown here, the decline in the current account surplus - driven by oil and gas exports - was masked in 2Q via Central Bank intervention. The private sector is sending cash abroad, which usually means its paying off foreign-denominated debt or else looking to park money abroad where it can. But Central Bank intervention buying up currency to maintain the ruble has tapered off, which makes sense given the reports about the recent attempt to get SOEs to fork over foreign currency. Once you price carbon, the private sector faces a dilemma that can’t be papered over via the current account surplus: where to get the best return on investment and can I trust the ruble? A weaker current account due to lower oil prices creates a persistent pressure that will then amplify as carbon taxes and border adjustments take effect.

The green bond market in Russia is, therefore, a necessary plug for that hole. Unfortunately Russia’s Central Bank, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Economic Development, banks etc. all have different stances on what even constitutes a green bond or green financing. For what it’s worth, Biden’s campaign has endorsed a nominal carbon adjustment fee for countries failing to comply with the Paris agreement (weak it may be), and the idea of forming “carbon blocs” within which you’d see frictionless trade is going to get serious consideration in the next few years. The “carbon balance of terror” is therefore becoming a fact of life, an input into national balance sheets once carbon is priced and taxed not only domestically, but on imports.

The irony is that Russia risks repeating the mistakes of its Soviet predecessor state. The decreasing efficiency of investment into oil and gas in the USSR steadily leached scarce capital resources for investment from other, struggling sectors of the economy - namely consumer goods. The situation now is different, but without a more developed domestic capital market and pro-active investment strategy, the failure to invest enough into energy efficiency and modernization will end up imposing a competitiveness cost onto the rest of Russia’s existing or potential export sector and reduce both national incomes and federal revenues. Think of it this way going back to earlier:

Export earning = end sale price - (domestic production costs + transport costs + tax (carbon or otherwise))

Carbon tariffs are theoretically paid by importers so it’s a dead loss to the foreign market and not the exporter. But cumulatively, reductions of income from tariff-related price inflation can hurt in time and, even more importantly, create a competitive advantage for national firms investing into production abroad making use of more lax regulatory and tax regimes and lowering labor costs while still adhering to their home market’s emissions regs. The tariff is another form of tax. Nations don’t “own” exports, companies do. A foreign company exporting from your country to another shows up on your national balance sheet and it can realize higher long-run earnings by avoiding the tariff if its trading a product in high demand with lots of competition and where marginal differences in cost can have a large impact on market share.

If the adjustment fee is charged to the exporter, which I suspect many will argue should be the case, then effectively a government is imposing a tax on the border for an exporter in its own country. That then raises the tax cost domestically for production for export, reducing earnings until capital is invested to lower emissions. It’ll be a savage fight in the WTO as to whether doing so entails preferential treatment, one Russia will surely take part in. I suspect that a Biden administration would fall closer to the EU, but a Trump administration would be utter chaos. Either way, the weaker the ruble becomes or remains, the greater the relative earnings for companies able to find ways to export to foreign markets, so long as they aren’t credit-constrained. Hence the green financing issue for Moscow and need to increase domestic demand for things made using green means of production. Both ensure stability, employment, and growth and in so doing, can improve fiscal stability and improve Russia’s balance sheets. But that threatens much of the constitution of the regime in its present form.

The “carbon balance of terror” is going to breed a new generation of global trade and financial imbalances without coordination. Those imbalances breed political imbalances and disputes. Globalization isn’t dead, it’s evolving. But whereas the G-20 bailed out the oil market - and the Russian economy - in 2009, this time there is no G-20. There is no G-7. There is as of yet little coordination and oil had already undergone a sea change in 2014. In carbon terror terms, the world is somewhere between 1913 and early 1937. The regime may prefer autarky, but there is no such thing in the developing world of carbon economics. That has to be a scary thought.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).