Top of the Pops

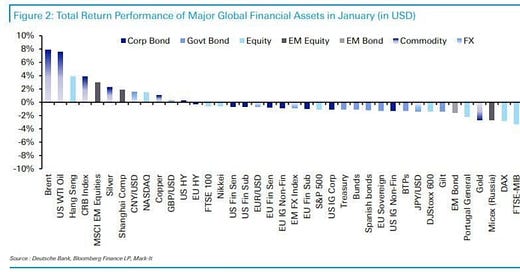

Oil’s back and surging higher, giving bulls a lot to look forward to in the months ahead. In fact, Brent was the best performing major financial asset in January:

Brent’s now broken $60 a barrel, smashing what remains a major psychological barrier on the market given that $60 was around the price floor OPEC+ aimed for after December 2016 and also, with its discount included, tends to be when West Texas Intermediate (WTI) sees serious daylight to invest into more drilling. Baker Hughes data showed drilling operations in US shale plays rising 9% in January, though that’s still about half the levels they were in January 2020 just before COVID hit demand in China. BH’s rig count was 392 at week’s end vs. 791 in January 2020. But these numbers are also a bit squirrelly since output per rig can fluctuate with the quality of the finds being drilled and the count in uncompleted wells drilled is a better leading indicator for how ready firms are to ramp up when the time is right. Shale drillers are still trying to win back Wall Street, and I’d expect more M&A activity seeking to drive down production costs and the cost of capital during the early phases of the current price rise. But if prices break past $65 a barrel or towards $70 because OPEC+ has managed to tighten the market enough, the economics of tanker shipping plus pressure to deliver returns to shareholders will send production in the US back up fast, especially if countries like Algeria continue to see lower output levels.

The real question for road fuel in the immediate term is how fast electric SUVs are ramped up in emerging markets and the US since sales of SUVs have skyrocketed as a share of total car sales after years of cheap road fuel with lower prices. It’ll take leaps and a lot of federal support, but I’m bullish on the US cutting road fuel demand faster than expected, which would psychologically be a sea change for markets, especially since China is happy to use massive levels of market intervention to expand EV penetration quickly and building charging stations and related infrastructure offer its investment-heavy GDP growth targeting a longer runway.

What’s really interesting to see is how unimportant the oil price has become for Russia’s domestic politics. Putin’s upcoming address to the federal government is going to focus on pushing forward socioeconomic development as its underlying theme while addressing the upcoming elections in September. Yet everyone realizes that while the budget may have been insulated from oil price fluctuations, high oil prices don’t really produce growth or higher incomes anymore. An influx of revenues from high prices will give MinFin a lot more space to spend ahead of the elections, and I expect that to be a talking point in a month or two. But it won’t actually resolve the types of challenges Putin and Mishustin are messaging have to be improved in some way. If prices crash (in relative terms) again from OPEC+ buckling under an influx of crude from the US and offshore elsewhere, however, it’ll keep intermediate demand up with higher output leading to more domestic orders but undercut investment outside of the oil & gas sector. It’s become a worst of both worlds scenario barring a big change in fiscal spending: oil prices can’t help the economy grow anymore, they can only hurt it.

What’s going on?

Russia’s running into a bit of a 5G international incident: its insistence on using the 4.8-4.99 GHz frequency band for future commercial 5G use is getting pushback from NATO members and neighboring states — namely Latvia and Estonia, but Turkey as well as Ukraine — because it interferes with military equipment. The International Telecommunications Union, part of the UN, has established a precedent whereby the use of the 4.8-4.99 GHz frequency range within 300 km of any air border or 450 km of any maritime border requires an agreement between governments. Russia’s pushing ahead the current generation of 5G without such an agreement anywhere, and it’s largely because the security services have hoarded the most cost efficient frequencies for 5G equipment for themselves, thus driving up costs for consumers while now creating a diplomatic headache. Basically, Russia’s telecoms sector has been forced to promote the frequency band for cell communications due to internal fights over control of the sector while it’s a frequency band other countries use for aviation transport. Odds are good European countries will block Russia’s use of the band in border territories, which could cost 30% of Russians’ access to 5G services without a resolution.

Despite demand hitting a 10-year low, wholesale energy prices in Russia last year reached record highs. Turns out its the use of non-market surcharges to regulate prices and profits to sustain investment levels hit a record high of 558 billion rubles ($7.5 billion) and current projections show prices may rise in European Russia and the Urals by 3.8% this year and by as much as 13.4% in Siberia:

Title: Dynamics of single-rate wholesale prices for electricity (rubles/MWh)

Blue = Europe and Urals Gray = Siberia

Though demand fell within the national United Energy System by 2.3% and there was a slight increase in generating capacity mid-year, the price level increase reflects something fishy with the 2019 market movement. The Federal Anti-Monopoly Service (FAS) launched an investigation into power generating companies that were hiking consumer prices wildly in H1 of 2019, leading to a 9-10% price increase over the forecast price inflation for the year which then led to a H2 price freeze. FAS has yet to publish anything or issue a statement on the findings. Last year, surcharges outpaced spot pricing as the main contributor to energy consumer spending by a big margin and it seems that the basic issue is the modernization program and policy support mechanisms in place. VTB forecasts end prices for consumers will rise 5.5%. Mishustin may have to make yet more promises of price controls if they don’t resolve the investment bottleneck fast.

It remains quite unclear what exactly the program will entail administratively, but MinPromTorg is set on offering financial assistance for the poorest who are worst affected by ongoing food price inflation after lobbying the cabinet with a presentation last week. Though a “food card” — seemingly akin to a quasi debit card system setting out what can be purchased — is not in the works, the language used by Vedomosti suggests something more like the American approach to food stamps. Aid is offered is given, usually with a price control or subsidy element, in exchange for ensuring that the recipients are buying goods from the right domestic producers (to help prop them up). The Audit Chamber supports the idea, likely because of how miserly income support was last year. Regional and city governments, particularly the social policy agencies, are keen to see the support head out the door, but rightly point out that mandating what consumers can buy is high-risk given allergies, dietary needs, and other factors the state can’t possibly plan for. The odds of fiscal policy support for poor families seems very, very high to help contain the damage from the current inflationary burst, but it’s also telling that so many are invested in trying to stop MinPromTorg from making a unilateral decision without their input.

MinEkonomiki is making another desperate play to boost Russia’s special economic zones (SEZ) as a means of ‘crowding in’ private capital with an amendment to the relevant governing law just submitted to the cabinet. It’s a bunch of a giveaways for anyone investing physically into SEZ: 5 years without paying any tax on profits, improving the tax rules for amortization, and returning VAT payments. They also want to link the creation of SEZ to areas requiring urgent socio-economic development, where large investment projects are taking place, or else to develop tech. There’s a marked shift in tone and approach out of the ministries in the last month. Clearly the presidential administration is panicked about getting the economy on track again, even if they lack the macroeconomic or institutional frameworks to make significant changes. The SEZ proposal also simplifies registering a business’ residency in a zone, the liquidation of SEZ when they fail within 3 years, and a carve out for the Northern Caucasus in a transparent gift to elites making money off of federal transfers to Chechnya, Dagestan, and the broader region. ‘Optimization’ continues apace.

COVID Status Report

New cases fell below 16,000 to 15,916 with reported deaths at 407. Moscow continues to show faster improvement than other hard hit areas with its infection rate per 1,000 falling towards the 7th out of the top 10 vs. St. Petersburg’s continued struggles:

MinZdrav put out new guidance on what medications have been certified to help recovery from COVID can be used by hospitals and prescribed by doctors. Clearly efforts are focused on getting over the hump nationally on the caseload and hospital burden faster and faster, including easing people’s recoveries. The line put out by Peskov is that 60% of the adult population will be immunized by summer, allowing things to return to normal in August. Something’s not adding up with the vaccination numbers, though clearly large progress is happening. Kiril Dmitriev from the RDIF is touting that all who want a vaccine will have one by summer, but that this won’t happen in the US or Europe until September or October. The gamesmanship is quite stupid. If 40ish% of Russians don’t want the vaccine, the virus will keep mutating and stick around while we have quite visible evidence vaccination rates in the US in particular are climbing quickly and off to a much stronger overall start in the UK (the EU is a complete mess on that front, to be fair). Something’s off with the data and assumptions, I just need to spend more time digging around to figure what exactly it is. The vaccine clearly works very well. That doesn’t erase the fact that the infection and death counts put out are clearly not quite right and data has been explicitly politicized.

Yield of Dreams

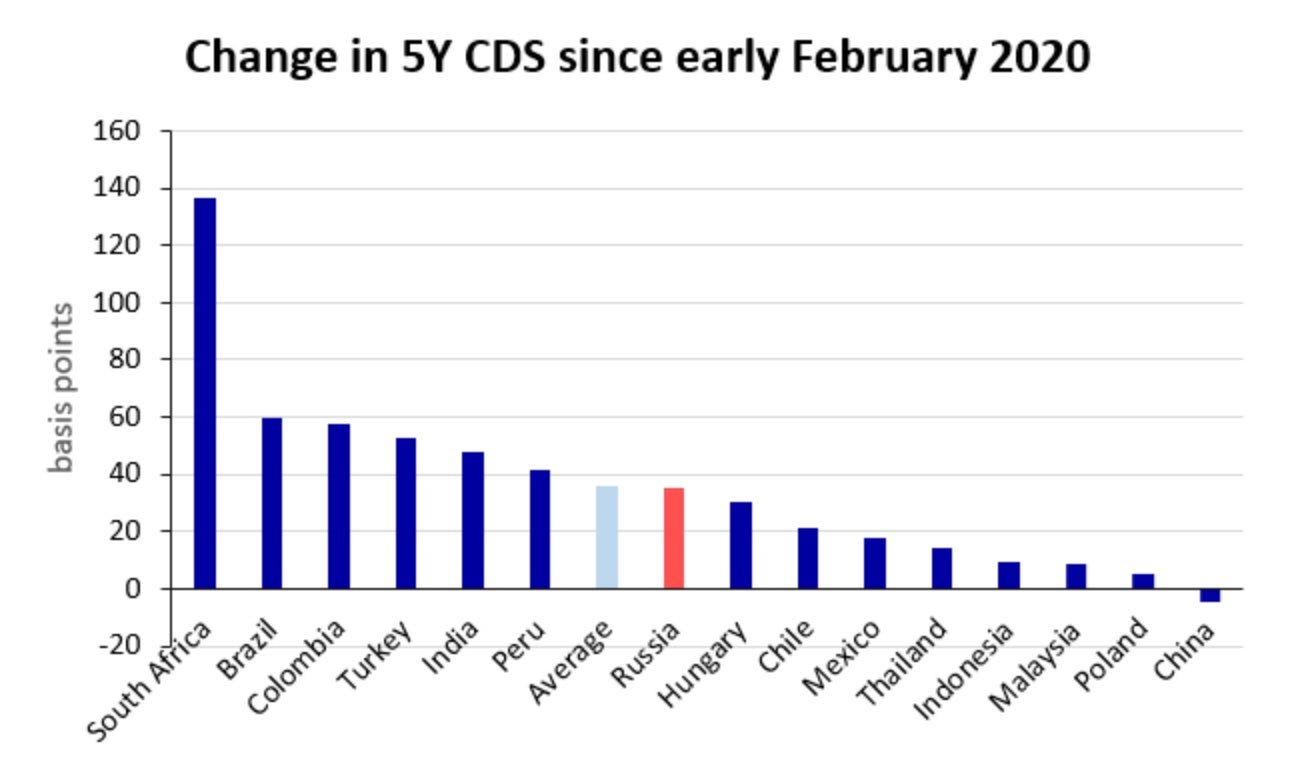

“If you issue it,” the man once said, “they will come.” So far, so good for Russian debt, even with the attendant political risk premium one would otherwise expect to be reflected in yields — the relative cost at which Russia can raise debt financing in relation to how much it has to pay out in coupons. Tatiana Evdokimova’s graph on Twitter, I think, tells us that investors, domestic or foreign, aren’t too bothered on that front concerning Russian bonds:

Russia’s risk premium increase is in line with the emerging market average and, while we have to see what happens next, there’s little evidence that the failed attempt on Navalny’s life and his subsequent arrest on return to Russia have affected investors’ expectations when holding Russian debt. That’s not to say there isn’t a persistent risk premium, but rather that it didn’t necessarily change much as a result of either. Fortress Russia is keeping a lid on premia. With the twin effects of the oil shock and pandemic on economic activity rocking most of the economy, Russia’s net external debt held to non-residents declined by 4.33% ($21.3 billion) to $470.1 billion — that’s about 27.5% of GDP using constant 2010 US$ adjusted with a 3.1% contraction off the 2019 figure. Given that the Central Bank holds about $590 billion in international reserves about $115 billion of liquid foreign assets in the National Welfare Fund, there is precious little default risk, so why not buy more Russian debt if you’re an investor Fitch has kept its stable forecast rating at BBB, noting only that the current protests might complicate domestic political priorities and contribute to higher spending levels, and thus affect the deficit in coming years.

The fun, however, stops there. One of the main reasons bond yields haven’t risen much is that, while higher than the target in 2020, the Central Bank has done an admirable job fighting inflation. Higher inflation devalues the future cash flow from the coupons paid out from a bond, which normally then pushes investors to only agree to purchase more bonds and finance larger deficits if the yield rises. That’s where inflation politics in Russia get tricky. From the Central Bank’s January review of inflation:

Red = expected inflation (w/ savings) Beige = expected inflation (w/o savings) Red (dotted) = observed inflation (w/ savings) Beige (dotted) = observed inflation (w/o savings)

Anyone who’s got money saved is expecting (and experiencing) a lower relative inflation rate than those without savings, as one would expect. However, this difference is made all the more salient since a lot of people owe bills that were deferred from various policy interventions but not forgiven or covered by state expenses. This is where the price control story gets a bit crazy and the monetarist policy focus of Russian economic, political, and security institutions shoots the Kremlin in the foot. Evdokimova similarly spotted last week precisely this story from the CBR about rising inflation expectations, which would necessitate a shift towards more hawkish rhetoric about raising the key rate:

The higher adjusted core inflation ticks up, the more pressure there is to raise the rate from 4.25%, and therefore choke off economic activity during a weak, supply side-led recovery. The Friday data release from BOFIT on PMI readings suggested that there was strong underlying positive momentum for the Russian economy:

Much of this is clearly from the virus getting under control, but given that small and medium-sized firms only accounted for about 20.4% of GDP pre-crisis and undoubtedly took a bigger hit than the rest of the economy and declined more, I’m want to assume that a fair bit of this uptick corresponds to higher agricultural earnings driving investments and intermediate purchases before the price control measures took/take effect, a slight rise in oil production, higher gas prices allowing for more cost inflation from Gazprom, and the start of a new budget cycle for state orders pushing levels more in one with what we’ve seen in 1Q, allowing for spillover from firms and contractors rushing to spend before 4Q ends and the budget cycle starts again. This activity, unlike past years, is dependent on the key rate holding at 4.25% alongside loan subsidy schema used during COVID. Mikhail Vasiliev from Sovkombank sets a base case of a key rate hold on February 12 by the CBR, with a gradual rise towards 5-6% by the beginning of 2022. But if inflation stays higher, they may have to act more aggressively.

The latest turn in the price control saga for the agricultural sector came last week as MinSel’khoz and MinEkonomiki settled on a pretty terrible consensus policy: they will impose a ‘floating customs duty’ set at 70% of the difference between the market price and the ‘base’ price. This will be enforced by exporters’ data handed over to the Moscow Exchange covering the cost levels of concluded contracts. The Exchange will begin to publish that data on April 1, and then after the market has a few months of that data to price in the effects, the duty will take effect as of June 2. Subsidies will be divided between regions by their productivity level to maintain firms relative profitability. The agencies argue exporters are withholding stores of grain from the market to drive up prices and want them to sell faster, while producers are panicked the new duty arrangement will be reviewed weekly and cause even more uncertainty. It’s clear that the current crop of measures aren’t controlling prices adequately, and that will push up core inflation considerably without further intervention.

This is where you get a rather funny situation for Russian macro. It’s (relatively) cheap to borrow and deficit spend at the moment, yet the lack of investment into capacity or income support has made the effects of price increases on foodstuffs more acute. The former has worsened the potential for otherwise short-term inflation pressures to stick, while the latter has reduced the capacity of small and medium-sized businesses to fully recover and, crucially, hire. The lower key rate now locked in place to help sustain the supply-side, credit-first crisis plan Russia went with only works to sustain deficit spending so long as they can keep inflation under control. Annual inflation has climbed past 5% for the first time in a year and a half just as there’s ostensibly evidence of a semi-solid economic recovery. The pricing crisis for basic goods is huge for the simple fact that a sustained spike in inflation at the beginning of a recovery that lacks large fiscal support is terrible news for the September elections, for Russia’s ability to maintain its spending priorities amid austerity (here’s looking at you, military budget!), and prevent further real income decline.

Aleksei Kudrin rather pointedly said that the lack of change in Russia’s political leadership is worsening public distrust and governance outcomes less than a month ago, clearly knowing that while he’s no longer really on the inside, he’s got space to make a clear point that will become more salient if they can’t get a handle on this ‘mini-crisis’ within a crisis. If inflation spikes any higher, the CBR will be pressured to raise rates prematurely, which will end up worsening standards of living in real terms and undercut the stabilization now underway. I’ve written before that Fortress Russia creates a Hobbit problem: Smaug may sit on all the gold he wants, but it’s worthless if it doesn’t actually pay for things. It turns out that because of the novel nature of the COVID shock, the timing of the commodity supercycle, and sustained food demand, Fortress Russia is a bit of a policy prison. With the current yield curve, any debt under the two-year maturity term yields less than inflation i.e. registers a net loss. That should push up investor interest in the mid-range maturities that could reasonably finance a fiscal expansion to create growth. Unless Russian policymakers realize that fiscal multipliers exist and could be worth a great deal given the country’s massive infrastructure needs, they’re setting themselves up for a year of widespread repression driven at this point not just by political paranoia, but by a failure to handle inflation with the key rate already at an historic low amid a significant economic contraction with long-term effects. I'd hate to be the guy breaking the bad news…

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).