Top of the Pops

Green bond issuance will be a hot topic in the next year to two as states, central banks, and state/private banks try to create green financial assets and resources to meet market demand. China’s issuances are making a strong recovery and on pace to break past totals, though there remains the lingering issue of how many Chinese green bonds are aligned with international standards — already questionable in many cases — rather than more lax domestic standards. Still, a ‘surge’ in China is still a quarterly issuance rate in the range of $17.5 billion. The market’s volume has a way to go, but it’s growing fast and may start having a more pronounced impact on capital inflows into China soon. We’re also probably a ways away from seeing China pursue the covered green bond route the EU is now looking at. Covered green bonds are collateralized against green mortgages, mortgages buyers take out to renovate and retrofit a building or buy a sustainable one. Houses provide a large stock of assets to collateralize and securitize, and we’d expect that green bonds will end up playing an important role in that financial machinery since it’s imperative that we reduce residential and office emissions:

It’s not a huge market yet, though its sizable comparatively to China’s overall market and I wouldn’t expect China’s property developers hitting GDP growth targets to follow this route until the political incentives for investment-led development change. Lack of data dogs green covered bonds built off of green mortgages — you have to collect tons of minutiae about old housing stock or offices and access lots of information banks historically haven’t held because they aren’t builders holding specs for new builds and so on. Russia’s far behind on this front, and I’m curious to see how building plans and the expansion of home ownership taking place as a result of the mortgage subsidy program creates new incentives to collateralize and securitize mortgages on Russia’s financial markets as they try to implement their own green taxonomy.

What’s going on?

Agricultural firms in Stavropol’ are calling for prices on fertilizer to be fixed to avoid potential shortfalls in production due to exorbitant costs. Fertilizer prices are up 60% at a minimum right now in Russia, and any decline in grain production will lead to an increase in flour prices as well as for bread and similar basic baked goods needed by households. The proposal sent by Denis Slin’ko, the regional rep for Delovaya Rossiya, to Yuri Chaika, rep for the president of the North Caucasus Federal District, calls for prices to be capped at increases of 10% against recorded price levels in June 2020. Ammophos — a highly concentrated nitrogen-phosphorous fertilizer — is the biggest source of worry as companies prepare to launch the harvest season and plant winter crops. Last year, at the average use rate of 100 kilograms of ammophos per 1 hectare of cultivated land, Stavropol’ producers spent 5.4 billion rubles for output. That’s expected to be more like 9.45 billion rubles or more (a 75%+ increase). In some cases, fertilizer costs have doubled. Stavropol’ only accounts for 4% of national grain production, but it’s the regional leader in high-quality grains used to improve the quality of flour. Increases in fertilizer inputs range from 15-40% in other regions. Considering that fertilizer costs are 20-30% lower for Russian firms than their Western counterparts, the situation is a bit mad. Price control measures can’t hold back commodity price increases elsewhere and higher input costs for agricultural output have to be passed on somehow if Moscow wants to maintain harvest and planting levels. MinPromTorg assured RBK that monthly cost increases don’t exceed 5%, but even a 5% increase matters a great deal for households these days.

Russia recorded another quarter of economic contraction, with GDP falling 1% according to the final tally from Rosstat, slightly better than MinEkomiki’s expected 1.3% decline. What’s bizarre is just how bullish Sberbank now appears to be about recovery — its research team is estimating 9% GDP growth for 2Q and a full return to pre-crisis GDP levels, which the Duma-affiliated forecaster TsMAKL puts at the end of 2021 instead. The problems are obvious looking at indicators state-owned firms aren’t pointing to. An Alfa Bank business survey shows 86% of respondents citing a reduction in Russians’ purchasing power, only 3% citing an improvement in demand, and only 15% expecting an improvement in the economy in the next half year. That comes on top of the obviously bad real income data shown well in absolute level terms by BOFIT:

The Bank of Russia now sees risk of a consumer credit bubble, which corresponds to a stat from finanz.ru — Russian consumers are borrowing 2 billion rubles ($27 million) every hour to finance their consumption while net savings withdrawn from bank deposits rose another 150 billion rubles since the end of March to 751 billion rubles ($10.17 billion) since the start of the year (now at a rate of 8.3 billion rubles a day). There’s no strong evidence of a real incomes recovery yet given the distribution of the economic recovery is heavily slanted towards exporting sectors and inflation is wiping out a lot of nominal wage gains from a tighter labor market. Sberbank’s thesis basically depends on an explosion of consumption driven by the current debt bubble lasting, while any return to pre-crisis GDP without an equivalent real income recovery means the difference will be generated bye household debts that will crimp future consumption growth since the Central Bank is stuck raising interest rates to curb deposit withdrawals and (supposedly) fight inflation. Foreign investors are also pulling their money out as BCS Global Markets estimates that the capital outflows from funds exclusively trading Russian securities have hit highs not seen since the start of October. Authorities can promise real incomes will recovery to pre-crisis levels by the end of this year, but Russian businesses realize that if consumers are maintaining their living standards with debt in an environment of high inflation, its of supply bottlenecks, and rising interest rates, they won’t be able to pass on greater revenues in the form of higher earnings, nor are enough Russians sufficiently invested in financial markets to provide some sort of wealth effect from the housing price surge to help.

A new study from the Higher School of Economics (HSE) in Moscow shows that universities steadily increased their funding levels for research between 2010-2019, accounting for 10.6% of R&D spending pre-COVID. The trend’s a positive one despite the frequently bad news of an increasingly politicized education system constraining the talents of many of its best researchers whose work doesn’t reflect particularly well on the the state of the country. It may also make sense from the perspective of economic policy — increasing funding makes it harder for people to justify leaving and, theoretically, creates more opportunities for public research to benefit the private sector. The picture looks different when you take constant prices into account:

Cyan = domestic R&D spending in universities, current prices (bln rubles) Orange = domestic R&D spending, constant prices Grey = % share R&D spending

Interestingly, the HSE report finds that about 32% of funding for these projects does come from the private sector. Also interesting is that the largest age cohorts of researchers are 30-39 and 40-49 with a significant drop in people under 30 entering these programs. That implies a future personnel crunch as retirements and early deaths affect the availability of skilled specialists for these institutions, or else reflect that more of them have left Russia or migrated to SOEs where the pay is better. Much has been made of how resilient and quality Russia’s human capital base has been despite the regime. While that generally holds up — Chinese firms, for instance, target the Russian market for its IP and human capital rather than consumers — there may well be a “sweet spot” effect demographically that’s become more apparent due to persistent economic stagnation, lower birth rates, and underinvestment into institutions and economic activity broadly on top of a weak legal environment to protect IP and foster innovation.

Aligning with OECD recommendations and norms, a draft law is now being pushed by the government that will make financial market organizations legally liable for failure to provide financial information about a client if they withhold information from tax authorities for their own gain, beneficiaries, or those directly or indirectly controlling them legally. Failure to comply will trigger fines ranging from 20-300,000 rubles ($271.40-4,071) based on the relative degree of inaction vs. intention. Financial assets are included, but real estate is excluded based on the current proposal — the state wants to know where you hold your money, not expose your corruption for public consumption. As of now, the Federal Tax Service (FNS) can only request information about specific transactions, whereas the draft law would widen the scope for oversight. It’s a good case of Russia benefiting domestically from a shift in international attitudes about taxation, tax havens, and tax transparency — it can adopt OECD recommendations at home while carving out financial secrecy provisions for the defense sector, sanctioned individuals, and more within the domestic banking system. Tax planners and financial advisors in Moscow recognize that the change will prompt more Russians with a fair bit of financial assets to park more money in offshore jurisdictions with weaker regulations, not a problem when you’re a developed economy with tons of safe assets for foreign investors but a more significant one for Russia since its loss of access to foreign financial markets means it has to mobilize domestic capital more effectively to sustain investment.

COVID Status Report

9,328 cases and 340 deaths were reported yesterday. Regions account for the slight change from the Operational Staff data that may portend a new generalized increase reflected by its data. Just as important, the week-on-week % growth data flipped significantly in the opposite direction to +5.2%. The hospitalization data in Moscow supports the start of a new surge in cases — from a few days ago courtesy of Foreign Agent Meduza. Yellow = daily hospitalizations Grey = 7-day moving average

Hospitalizations in Piter are up 27.6% week-on-week, forcing hospitals to bring back capacity specifically marked for COVID. The rise in infection rates in Moscow has medical experts now more comfortably talking about the arrival of a proper 3rd wave. The lack of clarity stemming from the informational control measures and gaps in reporting capacity for the Operational Staff has confused everyone about what to make of the current increase, even if one can actually trace its origins to March. Cases in Egypt continue to climb towards their New Year’s peak without any change in Russian policy about flights, while the decision to delay restarting flights to Turkey till July comes as Ankara lifts some restrictions and the caseload is falling at a consistent pace. Indicators aren’t looking great for the expected ‘boom’ in the months ahead.

No Boom, All Bust, Can’t Lose

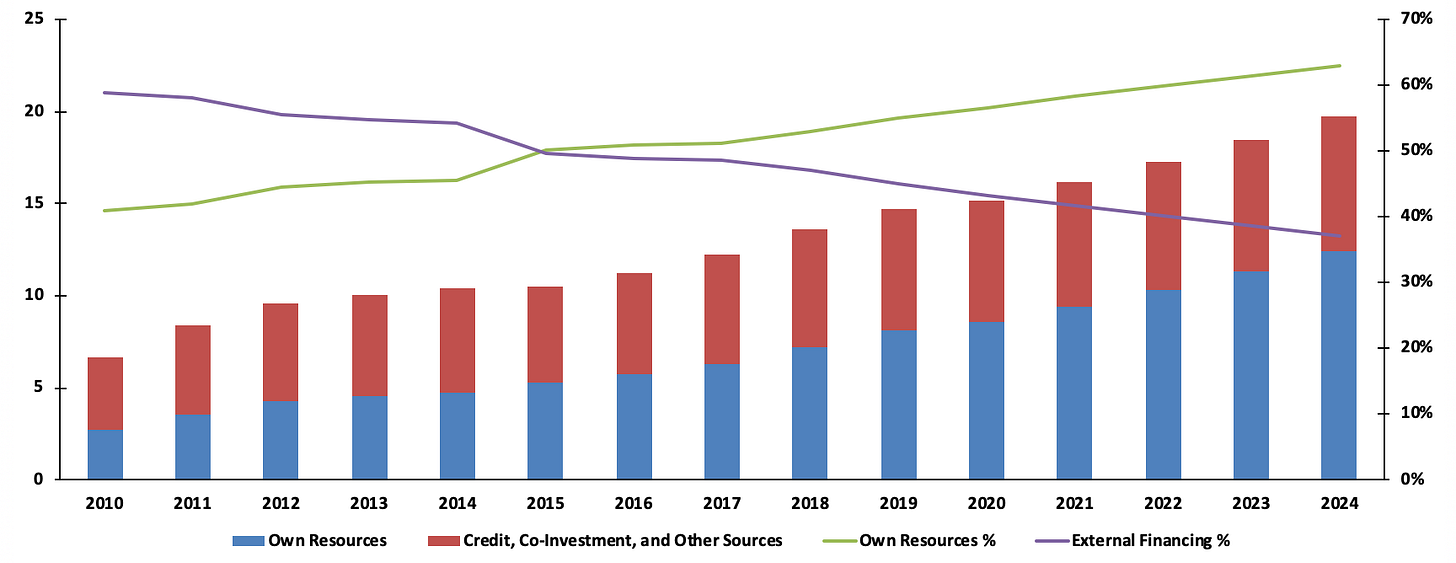

The White House and the Central Bank have reportedly come to an agreement to create new instruments and supportive conditions for an investment ‘boom’ into the economy through 2024. All told, these measures are intended to create the possibility of an investment expansion up to 10 trillion rubles ($135.7 billion) in total over that time. A working group tasked with working out the mechanisms necessary to hold corporate governance accountable and ensure stability of investment conditions will work as a ‘consultative organ’ for future policy work. In other words, they’re creating yet another bureaucratic outlet to heap pressure onto when the government’s in need of a new suggestion and the Central Bank can imbue it with more authority as an objective policy arbiter taken more seriously by the business community. It’s an attempt to stretch the credibility of the Central Bank more directly into the scramble for investment. This approach to development comes as a logical response not just to the fall in investment levels, but the sources of financing for fixed capital investment. LHS is trillions of rubles and I applied the 2013-2020 CAGR to the following years, noting that current prices were used up to 2020 so assume those that follow apply in ‘real’ terms insofar as the value of the ruble is fixed post-2020:

I didn’t have time this morning and the available data in constant prices was only an index level without an available nominal adjustment for exchange rates and inflation levels. I applied the same to the % share levels assuming no change just to see what it looked like. The cumulative increase in fixed asset investment without adjustments for real levels between 2024 and 2020 was just 3.8 trillion rubles vs. the 10 trillion they’re shooting for with this initiative. To be clear, we’re only talking about a ‘roadmap’ that the CBR and government have agreed for now and roadmaps tend to lead to nowhere in Russian policy. But we’re talking about tweaks to rules for syndicated loans backing project financing, tax breaks yet to be worked out by offered by amendments proposed by MinFin, the CBR, and MinEkonomiki by 2023, another shot at changing special investor contracts, and other platitudes. These are supposed to work out to a 250+% increase in the assumed investment levels going forward if we don’t do any other adjusting for incomes, commodity prices, or the likely longer-term scarring from the COVID shock. That’d be a huge step-change domestically, and one that the authorities also don’t seem to think poses any inflation risks, unless they’re more comfortable with it than we otherwise see from public statements and the one-two punch of MinFin’s accelerating fiscal consolidation and the CBR’s attempt to ‘normalize’ monetary policy.

They’re pulling the 10 trillion ruble figure out of a hat and running it through an inflation panic filter. It has no appreciable correlated basis in anything we can readily see in macroeconomic data, nor does it correspond well to the availability of capital via savings for investment. The dynamic of firms’ own funds financing more and more of investment isn’t really about sanctions pressure denying them access to foreign financing. It’s about the expansion of rentierism into more and more areas of economic activity, which has translated into higher costs for consumers and falling incomes since the state’s offered no real stimulus. Corporate profits are now improving, but we should be cognizant of the distribution of profits by sector and what profit levels mean given that Russians are burning through savings, pulling their money out of banks at a high rate amid inflation (un)certainty, and more indebted than ever:

The surge in profit levels does reflect a surge in consumption — that’s why wholesalers and retailers and manufacturers are killing it right now. But these profits also reflect price inflation and the firms passing on higher costs generally have much better access to credit and state support than households. The increase in profits can definitely correspond to a surge of demand, but the relative profit levels compared to past years suggest that higher profits may actually come at the expense of households since investment levels are still too low. For another example of how these figures get distorted, retail giant Magnit just acquired Dixie — Russia’s 3rd largest. The problem? Magnit is majority-owned by state bank VTB. The state is consolidating ownership in the retail sector into its own hands to be able to more directly intervene in price levels using VTB as a shareholder, which will also affect relative profit levels for that sub-set of the wholesale and retail trade sector.

Topping all of this off, the IEA is now openly stating that the policy scenario to meet 2050 net zero targets mandates no new investments be made into oil, gas, and coal output. International organizations can’t change the market by pronouncement alone, but this is a massive change and provides a weighty source of legitimacy for more aggressive proponents of green policies in the US and Europe. The following is again fixed asset investment, and note that non-hydrocarbon resource sectors were excluded but would bring up the investment share for that overall sector. LHS is trillions rubles:

Oil, gas, and coal projects would require ongoing fixed asset investment, but imagine just how bad Russia’s investment landscape would be if it had to radically restructure the capital spent on energy rather than other drivers of diversification. The IEA’s global investment scenarios make a mockery of current plans just about everywhere, but really cut to the scale of the problem facing Russia as the energy transition accelerates. These are the IEA’s investment needs to meet net zero:

$5 trillion+ annually only becomes sustainable if the OECD runs its economies hot for years to come. The surge in non-fuel commodities demand is going to trigger price inflation without a massive increase in supply. Russia can capture some of that, but the longer incomes fall or stagnate, the worse the inflationary impact of commodity prices. If they want a real investment boom, they better start thinking about demand and incomes using a new orthodoxy. The current one’s completely broken and at the whim of US, EU, and China’s policies.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).