Top of the Pops

I was unpleasantly surprised to learn that per Cambridge estimates, mining bitcoin now consumes as much electricity as Argentina or Norway:

Friends don’t let friends mine bitcoin, and frankly I don’t understand why crypto currencies are worth the speculation since we already have digital currency via our phones and credit cards, it’s just backed by an actual monetary authority and financial regulations that protect our deposits. Needless to say that bitcoin is terrible for the environment and the energy transition is going to have to take the rise of digital currencies seriously since it’s generating so much excess global electricity demand without creating any significant economic value, save financial speculation which might finance some consumption but probably not a great deal of it. In December, Russian company BitRiver imported $40-60 million worth of gear from Asian suppliers to build up 70 MWh of generating capacity to mine bitcoin — enough to power Russia’s bitcoin mining needs which is a big deal given Russia’s the world’s third biggest miner. For context, bitcoin’s now capitalized around $870 billion, roughly half of Russia’s nominal GDP in dollar terms, and Russian miners can benefit from subsidized energy prices so long as the current set of non-market mechanisms used to compensate firms prevent too big a spike in prices. I’m also curious how we make sense of the impact of bitcoin and related digital currencies on capital accounts (and in this case, current accounts as well since miners are theoretically providing a service that could be exported). While $870 billion is actually a trifling figure in the world of global finance, it’s becoming large enough to distort real economies in small countries in certain circumstances. Thing is that any financial flow pertaining to digital currency would really just show up as an ordinary one using fiat currencies until the conversion takes place via a platform that is legally situated under one country’s legal jurisdiction. If you buy crypto on Robinhood or other apps, your bank account is wiring the money over. There’s not a whole lot here news-wise, but it’s an area we’re going to see more political interest in quickly. We’ve already got the strategic commentariat in D.C. reaching for reasons that Congress has to move to beat China on digital currency and a digital yuan, which is now being rolled out with SWIFT in a pilot using the currency with certain online retailers for a week window. Russia’s opted for stricter regulation of crypto, but it’s unclear that’s enough. Wait till regulators try to rein it in by setting green energy requirements…

What’s going on?

The net average decline in real incomes reached about 3% for 2020, but in better news, average spending fell 4.4% and, as a result, net savings more than doubled from 2019 levels to 5.2 trillion rubles ($70.4 billion). This dynamic mirrors that of what happened in the US and other developed economies. Lockdowns and restrictions limits what people can spend on, and anyone relying on social transfers and support would cut extraneous expenditure as well if their job security was in question. Essentially, higher savings rates reflects uncertainty. Where I think the coverage falls short (and this is a problem in Europe and the US as well) is that while many tout the improvement of household balance sheets, much of that improvement comes from deferrals of rental agreements, ‘holidays’ for bankruptcies, and other measures whereby money that was owed wasn’t being spent, but has not been paid for by the state. So as measures have been and will be unevenly lifted, a lot of people living on the edge of the poverty line or the bottom part of the income stratum that saw its savings rise will be renegotiating a surge of costs that’ll benefit property owners or their creditors. My guess is that the relative share of that surge in savings is significantly skewed by income distribution, though Russia’s stagnation has actually driven down some measures of inequality in income terms.

The IMF’s report on Russia’s economic performance during 2020 is out with a handy reminder of the structure of Russian economic growth (and contractions) since 2014. Despite the impressive macroeconomic buffers and fiscal space state policy maintained to mount its public health response, long-term scarring is going to occur, a point that Kommersant’s writeup consciously leaves out while acknowledging that the larger role of the state sector acted as a shock absorber:

Title: Composition of growth/contraction of Russia’s GDP (%) — Purple line = growth/contraction (%) Green = imports Light Blue = exports Orange = investment Blue = consumption

As we can see, investment stopped contributing much to growth after 2016 and while consumption led growth in 2018-2019, much of that consumption is a mix of higher debt levels offsetting falling real incomes and a ‘substitution’ effect of Russian consumers replacing imports with domestic equivalents that may generate some growth, but not optimally. However, the IMF feels confident that long-term damage will be more limited compared to past crises because of stronger corporate balance sheets, years of preceding current account adjustment, and the state’s ability to pursue both fiscal and monetary policy counter-cyclically unlike in 2008-2009 or 2014-2015. There’s just one problem with that: the lack of scarring is because of how much scar tissue already covers economic sectors. The IMF wants Moscow to tax the oil sector on profits instead of MET, which is just not going to happen en masse so long as fiscal consolidation — which even the IMF acknowledges isn’t necessary — goes ahead. They’re probably underselling how fiscal policy will hurt the recovery, and induce more long-term pain.

The mortgage market keeps growing despite rising housing prices and growing concerns about a potential bubble. Averag rates are starting to rise considerably, however, which should be a red flag for consumer recovery in 2021:

Title: Base indicators of mortgage credit in Russia

Light Blue = volume of mortgages issued (blns rubles) Red Line = average rate (%)

The longer consumer spending is limited by restrictions, any health concerns, lack of vaccines, and so on, the more likely people will want to take their excess savings and try to buy property. But the rates will have to rise fast to choke off inflation and the group of Russians that can afford to borrow is steadily shrinking as they rise. Those with the highest propensity to spend most or all of their wages are probably locked out anyway. Worth watching into 2Q as more is opened up.

Sber has reportedly stopped work with subsidiary Cognitive Pilot on driverless cars and transport for the time-being for a funny reason: the lack of existing regulatory and legal infrastructure in place to support the deployment of driverless vehicles. Yandex is working on the problem as well, with both companies confident that driverless vehicles will come to market and be (somewhat) normalized within 10-15 years — the timeframe MIT assumes in the US as well. There’s also the Vienna Convention on Road Traffic from 1968 that technically doesn’t allow you to remove a human from behind the wheel, but given Russia’s selective interest in international law, I struggle to see that as a serious consideration. The biggest initial problems with deployment in Russia, however, will be cost and climate. These things are going to cost a lot more, and if western firms are able to borrow at lower rates and are willing to gamble on newer tech to meet self-imposed net zero targets, they’ll move faster. Plus highway driving in warmer climates is much likelier to be the first area to use self-driving trucks, and alas, Russia’s climate limits the areas where that will prove cost effective for an investment that only operates part of the year. I’d watch to see what Russia’s tech ecosystem does largely because it’s behind the ball on getting to market against competitors in the US, and while it’s a ways away, that’s going to disrupt energy demand and markets a bit as well as create long-term pressures on the type and scale of employment in the transport sector.

COVID Status Report

New cases fell to 14,494 and reported deaths came in at 536. The decline in new cases across the regions appears to be accelerating:

Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow Black = Moscow

It seems that things may ease up sooner than many expected if the present rate of decline continues through February and mid-March. Peskov was playing defense with the media over the 18% rise in Russia’s mortality rate for 2020, underselling how bad the pandemic’s effects were with a relatively meek line that it’s “harsh reality of the pandemic.” The new Rosstat data out makes Russia the worst performing country globally on a per capita basis for deaths caused by the pandemic (though the ‘cause’ measure gets tricky'). Digging through the numbers, it looks like roughly half of deaths last year were COVID-related. I doubt that story will haunt the Kremlin publicly, but it’s an area of weakness as they try to rush out vaccines as fast as possible. Systemic opposition parties won’t touch it. The non-systemic opposition probably will have to as part of its September elections strategy.

Labor’s love lost

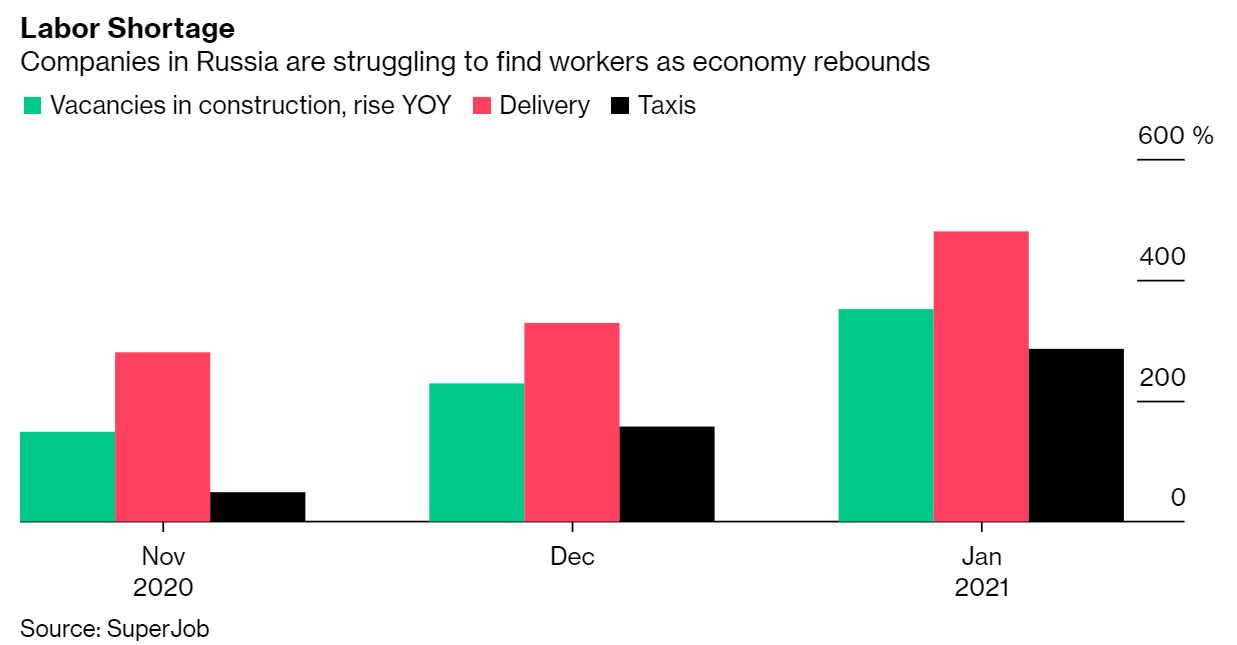

Bloomberg reporting on the job market captures one of the problem story-lines for 2021 and the economic recovery: border restrictions and the impact of COVID on Central Asia and Russia have cut off migrant labor flows and that’s starting to hurt Russian businesses. The following was data pulled from SuperJobs they put out:

The most visible short-term effect is in construction, where wages are being raised to attract local labor. It’s great news wages are rising, but Russia’s problems with stagnation have been about incomes, not nominal wage increases, and this is undoubtedly putting a bigger squeeze on housing prices as well as how far federal spending on construction and investment is actually going. Construction is being hit by being unable to fulfill contracts on time, too, not just a labor shortfall, which ends up changing end costs as bills rack up and projects are rushed to completion. But the wage story isn’t just about labor shortages. It’s also about government campaigning efforts to sell the recovery and setup September. Putin himself publicly admonished “certain [state] services” playing with pay statistics to make it look they’re meeting the targets set for them to raise wages for healthcare, education, and other public workers. Rising wages are a good thing, but if a sudden spike in wages comes about in the middle of inflationary surges for key consumer goods and spills over into the relative costs of services like taxis or of housing through construction companies charging more — and then construction input suppliers realizing that if prices are higher, why not try and charge more — it’s likely to hurt those living off of fixed incomes, social transfers, or else working in sectors where wages are stickier because the supply of labor is adequate at the moment. Everyone has a price for their labor, but there are jobs many simply won’t want to do.

That’s why despite a higher net unemployment figure than pre-crisis, the labor market appears this tight. I personally don’t think Rosstat’s calculations are particularly helpful because of how SOEs and large firms are tasked with creating jobs regionally, even if they aren’t efficient, and there loads more under-employed people to consider, but what’s really happening is the differential effect of losing cheap migrant labor that can be exploited. This morning, it came out that the government is considering easing entry restrictions and rules for migrant laborers. Why pay labor more when you can make sure consumers pay less? COVID-19 has produced unequal inflationary pressures in the Russian economy because of the tenuous balance between supply and demand for labor, commodity inputs, logistical bottlenecks, all of the real economy factors that monetarist analyses effectively ignore as the root of the problem. Rising prices for construction, one of the key means by which investment levels were maintained and people employed through the worst of the crisis, will take a big chunk out of any recovery this year even if it does reach 3% annualized GDP growth. Even assuming that better balance sheets leads to a better than usual post-crisis recovery, history does not suggest consumer demand just springs back into action.

If you want a quick snapshot of just how bad the Russian economy’s ability to recover using consumption is due to its structural failings, consider that based on Rosstat’s own reported consumer confidence survey, there hasn’t been a net positive survey result for consumer confidence since 3Q 2008. If you look at retail surveys going back over the same time, competition leads the way consistently as the biggest challenge they face, but consumer demand has basically always been a top-three concern. But historically, construction companies have never registered a lack of a qualified labor as a leading issue, which isn’t a great sign for 2021. If migration rules are eased, then Moscow has a different problem: how to prevent any cross-border transmissions from spreading into the general population assuming that a large minority continue to be vaccine skeptics and Sputnik-V may not work as well against new variants. That, of course, would reduce consumer demand. And that’s before one looks at MinFin’s latest ‘buried’ action.

According to finanz.ru, MinFin released 1.29 trillion rubles ($17.47 billion) from the treasury to state banks in order to provide more liquidity for the banking sector, which saw 4-year high records of liquidity deficits in January — as much as 800 billion rubles ($10.83 billion) daily on a regular basis. Basically, 1 trillion rubles MinFin kept that wasn’t spent despite being outlaid for the 2020 budget just ended up back in the banking sector to help cover reserves since people still want to keep more cash in hand and, crucially, more money is being drawn to buy houses or prepare for the incoming surge of costs many will face, especially as inflation nudges higher. There’s little cause to believe a banking crisis is anywhere close to breaking out again, but the irony is that if that 1 trillion rubles had been spend on support measures generating or sustaining economic activity and incomes, then the relative draw on savings and banking sector liquidity might well not be as bad, particularly if they hadn’t adopted the mortgage subsidy program that guaranteed an unequal recovery. And for good measure, MinFin is looking at applying a digital services tax to raise more non-oil & gas revenues, which of course would end up passing more costs onto consumers and the self-employed who have been making greater use of those services to get through the current crisis. Its actions suggest that higher savings aren’t being kept in banks, which speaks to precarious spending or concerns about economic precarity this year.

The current labor shortage spike also runs against the long-term, stable disposable income growth plans laid out by MinEkonomiki. Currently they want to see disposable incomes rise by 2.5% annually through 2030. For context, that would put disposable incomes back at 2013 levels by about 2025-2026 assuming they track fairly evenly with real incomes (they’re not quite the same category in theory, but in practice mirror each other more closely since Russians’ have much less invested in securities for retirement than you’d see in more heavily financialized economies). That increase would surge this year for those in construction, but then generate relative income losses for anyone buying property or else seeing their rents increase because property owners see rising values as cause to raise rents in major cities. While not monetary in nature, this inflation ends up spilling over into other areas of the economy quickly.

The reason I’m so focused on the inflation problem at the moment is the age breakdown of those supporting Navalny or else fed up with the system writ large. His support is mostly clustered among those who are 18-24 or 25-35, those for whom these troubles with wages and falling standards of living matters since they represent a sort of “denied future” despite persistently high levels of education and human capital available in the country. My thesis isn’t that 50+ year olds suddenly think Navalny’s attacks on Putin are true or correct, but that given that social transfers account for roughly 20-21% of the national income — skewed heavily towards pensioners by distribution — there is a political “trickle up” effect from these pricing pressures now starting to hurt middle class Russians who were hoping to get onto the property ladder. Your kids start having more plans interrupted, your grandkids are affected, you notice that the same set of things you’ve been eating for decades are costing you more but the latest bill announcement from Moscow doesn’t amount to much. It doesn’t topple the regime, but it diminishes the ability of the systemic opposition to channel public outrage and support if the KPRF or Liberal Democrats don’t win any meaningful concessions on social policy in public fashion. This worker shortage also hits on immigration as a political issue on top of the public health ramifications if Moscow’s been fudging the numbers and can’t get vaccines distributed to Central Asia ASAP. None of that is good news for the Kremlin, and all the more reason there may well be internal pressures to up the size of the spending package. I’m not holding my breath, though.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).