Top of the Pops

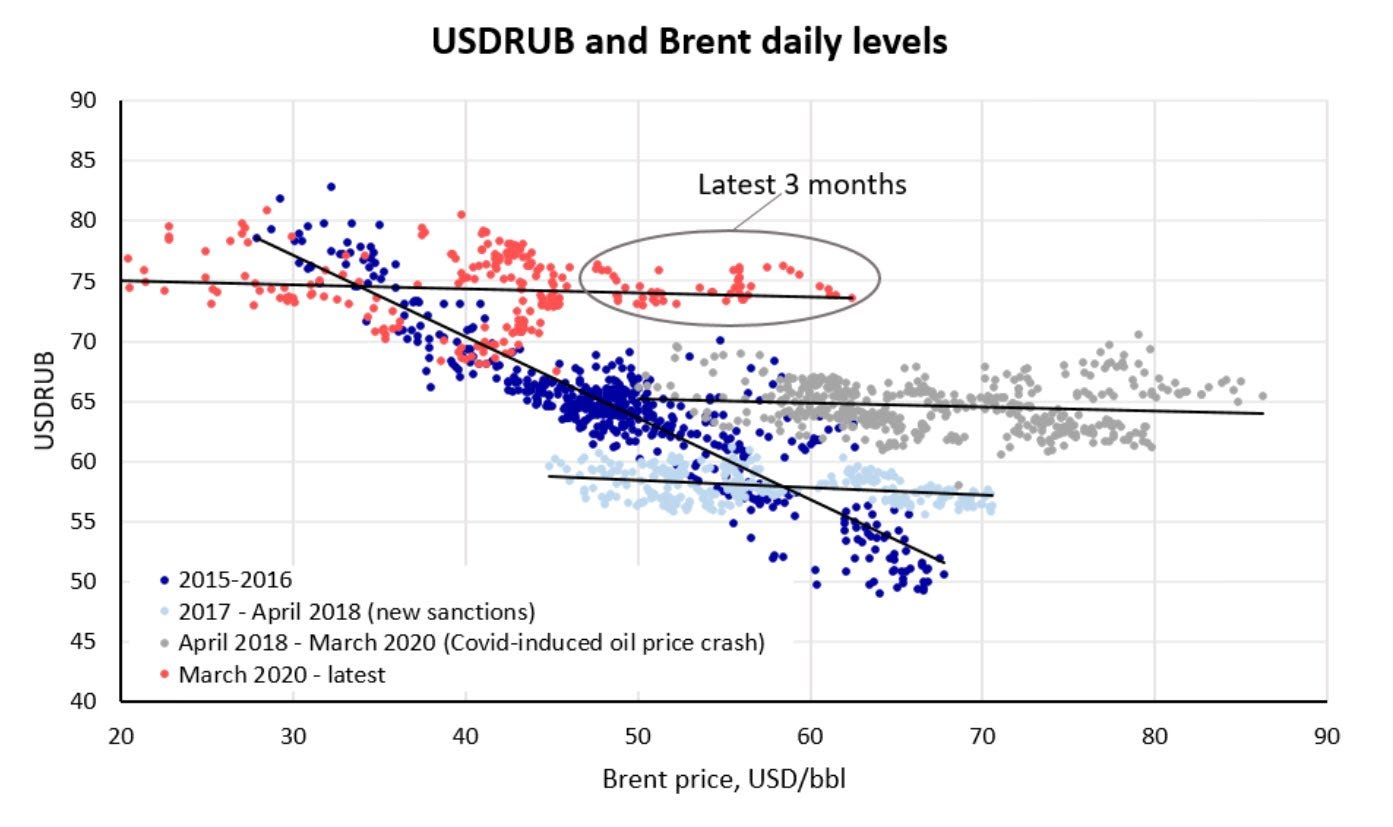

Two charts caught my eye and I think are worth returning to since there’s a growing chorus of analysts and outfits convinced that the real problem for oil is the lack of upstream investment triggering a large supply gap by late 2022, possibly pushing prices up to $100 which we haven’t seen since 2013/early 2014. The current spike from outages in Texas and OPEC+ cuts will subside on its own. There’s good reason to believe that ruble’s anchor exchange rate is now more like 75 to the US dollar rather than the upper 50s to 65ish range it had generally traded in prior to COVID. H/T to Tatiana Evdokimova:

That means Russians buying fewer imports, Russian exporters are more competitive and see their earnings rise when they sell in Euros or USD, and ostensibly less currency volatility which always makes markets happy. As Janis Kluge notes on Russia’s imports from Germany, 96% of the variation in import levels can historically be explained by variations in the oil price:

What’s really happening here is that while the exchange rate settles lower structurally over time to the benefit of domestic exporting firms, especially oil, gas, and mining companies, changes in the relative level of imports track very closely with the oil price level. So we’re left with the question of who’s actually importing X goods into Russia. The weaker the ruble becomes, the harder it is for Russians to afford western imports, the more dependent they’ll become on consumer goods exported from China (with the caveat that structural yuan appreciation now underway will eat into that eventually). But the companies importing goods and services with cashflows in foreign currencies aren’t really affected. For that reason, imports’ share of gross trade per balance of payments data for Jan.-Sept. actually rose slightly from 42% in 1Q to 44ish% heading into 4Q. The exporting firms were doing fine as commodity prices rose against a weaker ruble. Russian consumer demand would have recovered from its 2Q nadir, though not too much, but probably contributed to Russia running a trade deficit with China by 3-4Q. Russia’s economy hasn’t decoupled from oil, it’s actually shifted to an exchange rate regime designed to benefit its largest companies at the expense of consumers lacking domestic replacements for a wide range of goods Russia Inc. is still quite bad at producing.

What’s going on?

MinPrirody has a neat idea to help greenwash the Russian economy’s emission levels: factor Russia’s forests into any measurements of total CO2 emissions. The idea is sound on its face given that new studies show forests absorb twice as much carbon as they emit. On its face, the new methodology could reduce Russia’s carbon footprint (on paper) by a third given the vast size of the country and that forests cover 15% of its surface, providing an additional 270-450 million tons of CO2 of emissions reduction. It’s an obvious move to further reduce any meaningful commitment to net zero outcomes by exploiting how much nature has not been or can’t be exploited in the country, but worse, there’s no adequate data about the extent and effect of forest fires and other conditions that would significantly affect the carbon sink effect for any national accounting program. Then you have to work with the cadastral registry — a disaster — to keep better track of how many trees are felled, any deforestation or reforestation effects and more. We’re talking about a country where the overwhelming majority of cemeteries aren’t legally registered property because they were placed on land whose use was redefined after the collapse of the USSR and new restrictions were put in place, often making burials illegal per the law. It’s an initiative that’ll help the regime’s green politicking and give ‘Green Alternative’ something to talk about come September elections. The logistics, however, are a mess.

Despite the significant spike in sector costs in November-December from a mix of rising material costs and COVID-induced labor shortages from declines in migrant labor flows, the construction sector was showing signs of optimism at the end of 2020. Though overall construction was down 5.9% year-on-year — a strong performance largely reflective of how much state spending and investment projects were maintained at all costs — the overall impression is that the headwinds from 2020 were essentially one-off force majeure events:

Title: Factors influencing construction company’s outlook, (% balance)

Blue = expected # employed Red = evaluation of the order portfolio

The irony is that this data, which Kommersant notes would make the sector one of the top 3 most optimistic is bad. Like really bad. All we actually glean from this is that construction companies have to move ahead with projects and employ people, but the project pipeline still feels meh, if not outright bad, at best. Why is that? First, construction broadly is a top political priority — note yesterday’s release on Putin pushing the cabinet to work out regional funding for roads — and housing construction is one of the only sustainable ways to deflate the housing asset bubble triggered by last year’s mortgage subsidy program. Second, higher costs have been passed onto consumers thus far, but there’s every reason to expect that demand will slacken in 2021 if disposable incomes/real incomes don’t rise, which means projects funded by federal and regional budgets for housing will be pushed through likely trying to force the contractors to absorb more of the cost increases so that the ministries can claim fiscal discipline come the summer and tactically release money to buy votes for the September elections. Optimism isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

Russia’s non-resource, non-energy exports hit a record high for 2020 of $161.3 billion, the third year running they’ve reached record highs. If we extrapolate from the Central Bank’s Jan.-Sept. data and assume the same pace for 4Q, that comes out to about 44% of Russia’s exports, not that big a change from energy exports usual perch of anywhere from 62-70ish% of the export basket and largely explicable from just how low oil and natural gas prices were in 2-3Q. It’s still a big signal, and one that also likely reflects the renewed weakening of the ruble last year. But the incoming application of stricter export quota and duty controls on wheat exports alongside a likely smaller harvest will take some of the wind out the growth over the last few years — actually a relatively unimpressive $7-8 billion net increase. There’s also the question of how much the performance of domestic manufacturers correlates to non-resource, non-energy exports:

Title: Dynamics of industrial production, % month-on-month

Those increases mid-year were initially just making up lost ground and the December spike was a one-off while January clearly is an outlier too. If it’s not manufacturing making serious gains for export, then that means it’s mostly low-value added output, agriculture, or else refined fuels being exported thanks to domestic price controls and weaker consumer demand giving refiners a chance to try and dump product into Europe, Turkey, anywhere that’ll take it (not China given its glut of refining capacity). So these gains largely track with wheat harvests, plus a little extra around the edges, and cross-subsidies from the energy sector help all of these exports as well.

Glonass, Russia’s own GPS operator, is launching a subsidiary to act as a virtual cellular telecoms operator in a bid to corner services to support the rollout of the Internet of Things (IoT) across the country. The firm, Glonass Mobile, has received an operating license through 2026, is only 34% owned by Glonass. General director Ksenia Svintsova owns 49% and the rest goes to Valeriy Sudakov, which suggests this is a pet project hoping to succeed at scale and extract rents by cornering out any competition using Glonass as a lobbying platform since its the sole operator for the national positioning system. The business model, however, is a bit different from other cell operators. Instead of monthly or floating tariffs to pay for time using the cell network, subscribers pay fixed costs (presumably on a monthly basis) to download their profile into the company’s system which then coordinates the connections between appliances, other companies, etc. with the guarantee that said profile is kept safe and data kept private. It’s akin to making SIM cards virtual. The company will then distribute these e-SIM cards as a sort of service alongside existing cell operators. This could make money by managing apps i.e. automatically switching customers to more attractive plans offered by one’s cell operator to save money or else offering to change your operator as needed while also building a shared infrastructure for the IoT. No one has any clue if this is going to work, and the entire business pitch reeks of rent-seeking. By posing as a service offering convenience, they’re really trying to do is seize a market monopoly so that the price of the service won’t reflect actual competition that would effectively help subsidize Russia’s domestic tech sector at the expense of domestic consumers. Silicon Valley would be proud.

COVID Status Report

New COVID cases fell to 12,828 per the Operational Staff data, with 467 recorded deaths. Karelia and St. Petersburg are increasingly laggards for their infection rates per 1,000 while the falloff across the regions continues elsewhere and Moscow has gotten its cases down to under 2,500 a day (officially). The heat map showing total cases helps the regime make the case that things are normalizing despite what’s proving to be a very slow vaccine rollout:

Alongside the rather incredulous statistics, PM Mikhail Mishustin just authorized the use of almost 50 billion rubles ($677 million) from the government’s reserve fund where it parks its excess oil revenues to medical professionals working COVID wards and on COVID care generally. Let the vote buying commence. Though things have clearly gotten better overall based on hospital reports from the regions, it’s very hard to believe the vaccines have yet had any significant effect on infection rates given the regional data available. So what’s happening instead, I think, is the targeted use of spending and support to quell any discontent from those best positioned to know what exactly is going on and help families who’ve borne the brunt of the pandemic at home while the infections continue to come down and more doses are handed out strategically with the intent of targeting the at-risk or those who are the greatest spread risks. Rospotrebnadzor just issued guidance that international students from countries Russia has resumed air travel with can return to study in Russia only if they’re tested twice for COVID. Things are improving and very slowly normalizing, but I’m waiting for Rosstat to release excess mortality data for 1-2Q of this year to see how accurate the Operational Staff reporting has been since the vaccination campaign launched in mid-December.

We Need to Talk About Bitcoin

A story that caught my eye on Monday has been percolating a bit and one that’s really useful when thinking about how atrophied our analytic vocabulary when making sense of Russia’s reach in global affairs has become. As of last week, the global value of the money supply currently saved in the form of Bitcoin exceeded that of the Russian Ruble. A cryptocurrency that can barely be redeemed for any goods anywhere whose value is insanely volatile and therefore a terrible unit of account for transactions or reliable store of value (it can’t just go up forever) is in greater demand from global investors than the ruble, which is backed by one of the most hawkishly austere governments on the planet that stockpiles gold that, while suffering from the political risk of sanctions, has macro economically adapted to them and contains adequate domestic demand for its sovereign debt to make up any shortfall from foreign investors worried about the political risk of sanctions. In short, the Kremlin lacks much of the structural power of Generation r/WallStreetBets in global finance. BlackRock, an institutional asset manager controlling $8.7 trillion of assets, now uses Bitcoin derivatives as part of its portfolio planning as institutional finance has embraced it, even if in small volumes, as a hedge. Consider that, and the political context around it.

China’s push to create a digital yuan will change the transaction costs of various dealings, but its real value lies in the power of financial surveillance once a currency is completely digitized. You can’t find ‘unmarked’ digital yuan, or do something under the table. Every transaction will be recorded by the system the People’s Bank of China is rolling out alongside the recent agreement with SWIFT. Russia’s own approach to the digital ruble is to cast it as a matter of competitiveness, but for the life of me, no one has a compelling narrative as to why we need to create new digital currencies. Daily transactions in most of the West are already digital, a matter of tapping your phone or card to something that moves around money on spreadsheets. This has become especially acute during the pandemic. And while there may be delays moving money between countries you don’t see with Bitcoin, capital controls are actually a good thing when they help stop speculative inflows or panicked outflows from triggering currency crises or financial imbalances that send the real economy into hyperdrive or a tailspin to the detriment of most of the country. Really, they’re trying to get ahead of what Bitcoin is now doing, if at the margins, to global finance so it can be surveilled. Yes, preventing financial contagion from bubbles matters here too, especially if derivatives trading keeps growing, but at least for Russia, the country’s financial market is not deep enough and inundated with those instruments to really be too concerned on that front.

Bitcoin is a good example of how states are forced to react to market developments from abroad that at first glance, have little to do with anything significant or real in the economy. That Bitcoin is an asset in greater demand than Russia’s currency points to the power of markets, companies, economic institutions beyond any border and that even when countries are able to exert some degree of substantial sovereignty over their economies, they constantly face pressure at the liminal points where, say, export prices and practices affect domestic industries or emerging norms and standards force them to compete and innovate. There’s a report out that Navalny’s team in Russia has received 658 Bitcoin in donations since December 2016, receiving 6 worth roughly $304,000 this year alone. The Moscow Times ran a great piece on this phenomenon last week and here’s the link to Navalny’s team’s Bitcoin wallet:

Regulations are sure to follow since the cryptocurrency undermines attempts to regulate foreign money finding its way into civil society organizations. Government officials have been banned from holding or using Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies and have to unload their positions by April. The Duma is considering a bill that would classify digital assets as property to be taxed mandating the declaration of receipts or write-offs of crypto assets in excess of 600,000 rubles annually. If the ruble devalues more, the tax ceiling gets lower and lower.

This is a great example of the problem of structural power Russia faces. It has virtually none when it comes to global political economy. Its domestic market, despite being large, is unattractive for foreign firms so long as disposable incomes keep declining as they have in relative terms since 2013. The consumer inflation crisis with food staples has gotten so bad — thanks in part to the completely backwards policy response focusing on supply-side controls for a leading export sector exposed to a global surge in prices it could be profiting off of instead of income support — that Putin has ordered the government to consider creating a “food card” for the poorest Russians, effectively a food stamp system ensuring access to basic needs at costs directly fixed and picked up by the state. Rosstat continues to change its methodology constantly to make things appear to be better than they are while price increases pick up speed.

The country’s tech ecosystem, fantastic at rolling out digital services for the state — and beating out countries like the US on adoption in the process — lacks adequate R&D and is becoming reliant on China, its market, and its firms for future sales growth and innovation. That despite the fact that many Chinese firms have long relied on US or European tech for their own gains, making this shifting market and political alignment a matter of Russia chasing the country that copied and chased the West. If Russia had cultivated ties with Taiwan, it might have an easier time working with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Ltd. (TSMC), the global leader in the insanely capital intensive industry of semiconductor manufacture. TSMC pioneered the business model of manufacturing whatever proprietary design other companies would contract it for instead of building what it designed in-house, an innovation that has made the de facto bottleneck in global semiconductor production. Car manufacturers have had to pare back assembly because of a shortage of chips for cars dating back to last Spring when TSMC and others cut back on the relevant output expecting car sales to fall from the pandemic. This is something Russia really needs to figure out if it wants true tech sovereignty. Of course, Moscow could never build a foreign policy around one company with structural power exceeding that of many states if it would ruin ties with Beijing (with its own semiconductor ambitions), a legacy of the foreign policy orientation around Gorbachev in 1985-86 that continued through Primakov and Putin from the 90s till today.

Take oil. Over a third of Russia’s remaining reserves aren’t profitable to extract, its tax system disincentivizes investment which means it reacts slowly to the market, and Saudi Arabia showed last year that in time, Russia will be one of many countries losing marginal production to competition as production costs elsewhere fall along with global demand in time. It’s a marginal producer despite being a large one. And much of the stability Russia has maintained since 1999 came about as a result of the lessons of 1986 and 1998 i.e. that its export dependence on oil & gas could be mitigated by under-investing domestically as opposed to the chronic over-investment that was misallocated in the late Soviet economy, triggering a massive inflationary crisis since people lacked enough consumer goods to consume and excess savings had nowhere to go in the Soviet system. That chronic under-investment going back to 1999 correspondingly empowered the political constituencies responsible for generating the most tax receipts — oil & gas — or employment and tech — the defense and security sectors — which was then reflected in foreign policy preferences since there simply weren’t adequate counter-weight lobbies at home to push back against the often self-defeating nature of Russian interventions and coercive activity, lest we forget the Kremlin’s obsession with managing the Gulf oil producers and Middle East since 2014-2015 to avoid what happened in 1986. The Saudi decision to flood the oil market and break OPEC’s power to politically set prices due to the oil glut of 1981-1985 slammed a Soviet budget reliant on exports for over 10% of its earnings, another Gorbachev-era legacy shaping the county’s politics today.

The larger point is that global economic forces shape the decisions made by states far more than states care to admit, just as markets are shaped by political forces far more than most businesses would likely care to admit. Russia’s relative absence from the world economy despite its size creates a multitude of pressure points, one of which being its financial underdevelopment. It’s insane that Bitcoin is a problem for the regime since it may finance opposition activities — mostly from Russians mining it themselves, I’m certain — and at the same time, is now seen as a more valuable asset than a ruble. Russia’s presence globally — in Ukraine, in Syria, in Libya or Sudan or the Central African Republic, in Tajikistan or Nagorno-Karabakh or even in the disastrous leaks about cyber attacks — is constantly mistaken for power. The word influence is easily abused. Influence is great insofar as it can get Moscow a seat at the table for talks about this or that. Rare is the time Russia has anything approaching significant power to resolve a problem without considerable help from others, and its pursuit of that influence to be able to assert its interests parallels the steady decline of its structural power within the global economy. Who knew that the ruble’s place in the international currency hierarchy would be laid low by a cryptocurrency. Russia is generally conceived of having interests and an approach to world affairs somehow divorced from its economy, as if the economy is merely a latent base of power from which security and military elites draw power to pursue their interests. That makes less and less sense the more powerless Russia is in the face of the whirlwind a rapidly evolving global political economy represents.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).