Top of the Pops

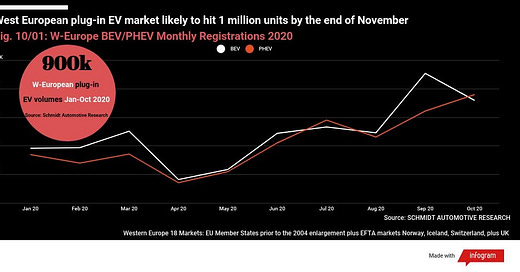

Western Europe’s EV market is looking stronger as it’s expected to pass 1 million plug-in units by the end of November:

Car fleets take a long time to turnover. A car can last a consumer 10 years, after all. Now that the UK appears to be mulling a ban on ICE vehicle sales by 2030, the ‘on-ramp’ to try and switch consumer behavior, accelerate adoption, and convince investors and firms to sink massive amounts of capital into building out infrastructure is looking better for Europe and any Japanese car manufacturers watching the European market closely. This well could become an important point of contention for a Biden administration trying to negotiate trade and take care of the Big 3 in Detroit while they make the leap themselves.

What’s going on?

In a hiccup for the rollout of 5G in Russia, subsidiaries of Rostelekom and Megafon are being denied the right to use frequencies in the range of 3.4-3.6 gigahertz for 5G testing because *drumroll* those frequencies are being used by satellite equipment operated by the country’s security services. The National Security Council has upheld the decision after coming out against the use of those frequency bands last August. By forcing these companies to look at higher frequency bands, the effectiveness of the network will be diminished and costs likely passed onto consumers. It’s a perfect example of a cost imposed on the population that has a net negative effect on economic performance in order to sustain the defense and security establishment’s privileged place.

A new report out from the Central Bank’s economists Dmitry Orlov and Evgeniy Postnikov tells an interesting story about the relationship between unemployment and inflation in the Russian economy. The novelty of the study lies in the realization, self-evident yet difficult to measure, that Russia is not one labor market, but highly segmented geographically. The following map shows, by region, the % of unemployment at which inflation accelerates (NAIRU = non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment):

What’s interesting is that the study finds that higher regional unemployment levels are, in fact, pro-inflationary. I need to spend more time with the report as I just skimmed it, but on its face, the finding makes sense. A loss of productivity, output, and efficiency in the regions or, conversely, inflation in urban centers with a low or nonexistent NAIRU are ‘exported’ internally because of regional imbalances. In other words, there is external and internal inflation occurring differentially within one economy. Anyone who’s bought a movie ticket in a rural movie theater vs. a city one knows that’s obvious. How else did I pay $2.50 for a matinee in Niles, Michigan compared to $11 a pop in Chicago when I was in high school? But Russia’s unique size, logistical challenges, and industrial development render the way inflation is transmitted between regions a bit differently.

Vygon Consulting estimates that the retraction of tax exemptions for oil producers will cost them 1.15 trillion rubles ($15 billion) by 2025. Turns out that raising tax rates on the sector while forcing it to restrain output and prices are low is going to negatively affect companies’ investment plans. The issue isn’t just losing revenues to the budget, though. In the longer run, the budget might lose out as well. MinFin seems to be betting that a weaker ruble and rising oil price will save investment plans, while Vygon rightly points out that without a unified tax system with better categories distinguishing tax rates by types of project, long-term investment is threatened. Short-termism wins again.

MinTsifry is supporting a bill that would establish an integrated system for identification and authorization to be used by digital/telecommunications service providers and it’s got a catch: the private sector would be forced to use the system used by the state for its own electronic services, including banks and anyone using a payments system. As I understand it, Russians’ personal data would be accessible via a unified system by using subscription data i.e. one’s phone number for databasing purposes built out of the government’s platform if it were to take effect. The bill extends rules pertaining to legal entities that are registered to citizens, but calls for rules that would require any service provider such as a bank to ask for consent before handing over requested data to the state. The main issue now is that the new system is likely to impose additional costs for businesses. Still smells like a funny proposal and one worth following for further amendments.

COVID Status Report

Over 22,400 cases yesterday. It looks like regions are now looking at opening up more facilities specifically for COVID patients, as has now happened in Tiumen. That’s notable given a prosecutor in Chelyabinsk found that an October order issued by the regional Ministry of Health directing first responders dealing with emergency calls not to help certain categories of patients. Regional governments can’t ration care that way, even if the center wants to force their hand by continuing to be utterly useless during the current wave.

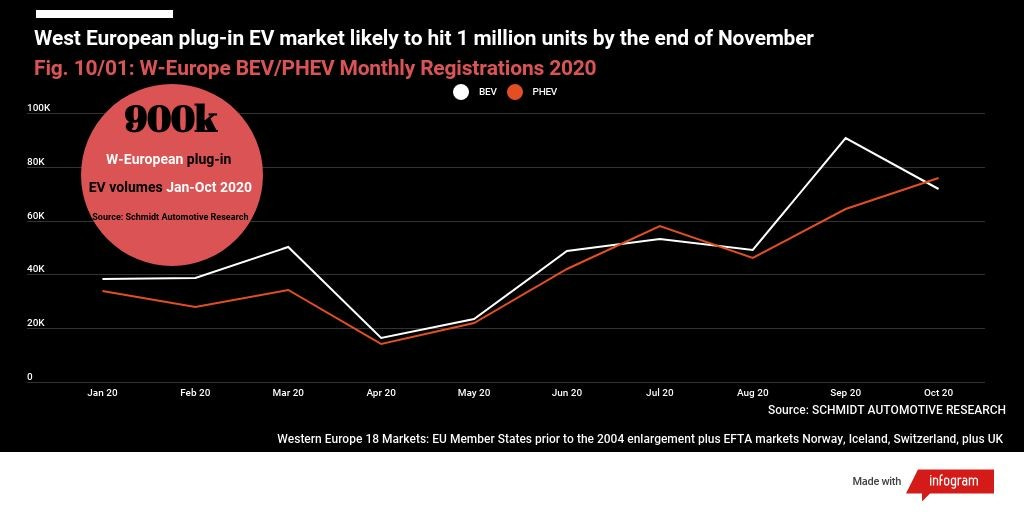

This graph just sets GDP growth figures against infections per day. It’s clear from the underlying trend that slightly higher commodity prices have spared the worst, but it may tick down again as the infection continues to spread.

Oil Bulls on Parade

It’s sad to say that some people just never seem to learn:

I’m not going to look like that. For one, I have decent reflexes. For another, a permanent oil demand drop doesn’t necessarily have to be evenly distributed, can actually lag a few years in the data depending on what metrics you use, and also isn’t best reflected by India. This is the type of hot take people at the Motley Fool or the worst contributors for Forbes love to run with because it feels self-evident and comforting to know that they’ve gone long for the right reasons, yet have little interest in what’s happening to the superstructure of the global economy shaping the present and future of oil demand.

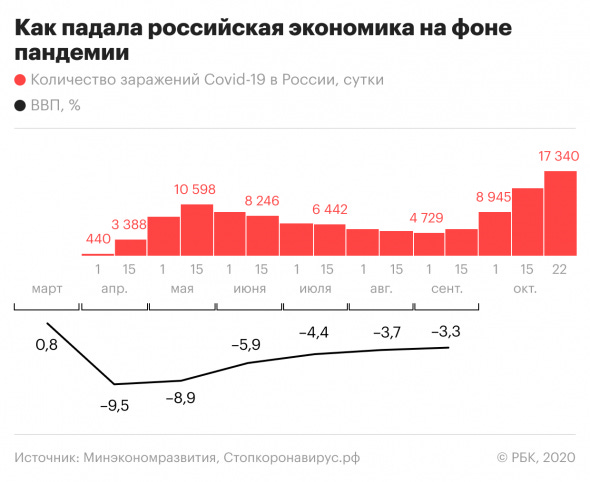

India posted its first oil demand growth for October since February:

The HFI view isn’t confined to a few. A lot of traders and Tuesday morning quarterbacks sitting in the tall grass are confident that the latest news from Pfizer and now Moderna are going to contribute to a structural bull run for the market. However, they don’t seem concerned that OPEC+ cuts at 7.7 million barrels per day are, largely by consent, still hanging together through January with some members even pushing for deeper cuts. At the same time, US shale is still expected to be producing over 7.5 million barrels per day in December — a figure that undoubtedly rises if prices really do enter a long-term bull trend — and then there’s the part of the market that’s just forgotten about any uncertainty from the Biden administration on oil sanctions (I again think Venezuela is a much likelier recipient of relief than Iran, especially since Biden’s path to victory did not include Florida). But even on the merits of recovery in a country India, the thesis has to be unpacked a bit more, particularly given how important the commodity cycle is for economies across Eurasia. Using BP just for a spot-check reference:

As you can see, India’s oil demand growth looked like it was ramping up bigly after a trough in 2013 when Modi came into power in 2014. But his own policies have not delivered particularly strong growth and the considerable appreciation of the US dollar in 2015-2016 from marginal changes in the Fed rate and other currencies coincided with a slowdown in demand growth in India. That it was lumbering into an anemic 2% dead zone — a bad sign for an emerging market with as much growth potential as India — prior to COVID suggests something else is going on. One of the biggest growth areas for fuel demand is LPG, which Modi has supercharged by launching a program to provide it for free to rural households. Add in lockdowns keeping everyone at home and cooking and suddenly the picture looks a little different since refiners will have to run barrels of crude to meet demand without necessarily being able to place each segment of the barrel by product. However, refining capacity in India is almost back to full capacity as gasoline demand has risen, so there’s definitely a growth story for underlying demand. There’s just little reason to see it surging upwards again based on India’s underlying economic performance, particularly since it’s such a finicky negotiator for trade and is now on the outside looking in for the RCEP and other initiatives while the globe tries to find ways to reduce its exposure to the Chinese market. As a side note, this quick grab shows that the rupee seems to track more consistently with the ruble since the oil crash, suggesting that shifts in the value of the US dollar really matter for understanding demand growth capacity and while a Biden administration may signal a weaker dollar, the effects of a weaker dollar are not going to be evenly distributed. This is the ruble against the rupee:

China escapes these traps by using debt issuances to meet its GDP growth targets and keep industries consuming while managing its exchange rate against the US dollar actively. Yet until there’s a clear demand side policy in China, it’s unclear why oil bulls think demand growth is going to continue on the same trajectory. Debt only gets you so far, even if it can always be restructured domestically. Per that article on Vygon and Sechin’s catastrophizing language, it’s evident that MinFin is banking on a price rally next year along with traders like HFI.

Good vaccine news is driving the dollar down, which should support demand in emerging markets. But a weaker dollar is going to worsen Eurozone deflation (at least as of now), which will ripple into Russia and pose some problems for emerging markets as well. If the CNY appreciates properly, that should limit the growing gap between industrial recovery and retail recovery in China:

But it won’t, because even with liberalization measures from the PBoC, they can’t kill the export rally now, especially with demand in Europe teetering. The lack of synchronicity remains a big impediment to an oil bull market, let alone that demand decline may set in among many OECD markets with policy responses in the next year. It seems that oil bulls are still only focusing on a few moving parts and not a holistic view when making their bets. But markets aren’t rational and traders don’t have to be.

We are Martial

I stumbled across a report from last year on fuel use and the US military that’s worth having a think about. It struck me that the US military consumes somewhere around the order of 270,000 barrels of oil per day and its fuel emissions account for as similar total as all of Romania’s emissions. The military is part of a much broader array of sources of emissions — and resource demand — that don’t neatly fall within the purview of any single government or accountable body. Maritime shipping accounts for about 2.5% of global emissions, around 940 million tons of CO2 a year or close to 1/7th of all US emissions, hence the role of IMO and other transnational but private organizations responsible for setting fuel standards, emissions reduction targets, and more. How does that work for militaries?

To be fair, the US military has decreased its net emissions over the last decade and has been at the forefront warning Washington lawmakers that climate change is an existential security threat. But those emissions reductions are primarily at fixed installations and facilities i.e. bases for which electricity can be generated using cleaner sources of power, micro generation capacity, and related options. No one has an effective fuel substitute for a B-2 stealth bomber or a UAV. Power switching hasn’t yielded the most gains. Avoiding waste like idling vehicles and focusing on conservation and fuel efficiency have thus far.

In a practical sense, reducing oil usage for military vehicles could, in theory, reduce the vulnerability of supply lines in combat scenarios and military campaigns. A decade ago, I’d have probably told you, with what little I knew then, that oil dependence was a risk for US foreign policy because it was keeping us fighting in the Middle East for no gain. That’s not true anymore. The market evolved. But these types of considerations still matter, as does the fact that any increase in defense spending for an armament program that entails deploying yet more troops, materiel, ships, and aircraft into the field means an increase in fuel consumption and higher emissions. Escalations in defense spending likely make it harder to reach climate goals. I couldn’t find anything comparable for the Russian military, but it’s safe to say fuel and emissions waste is comparatively higher, especially since fuel is subsidized domestically and Russian refiners are constantly playing catchup with European standards. Climate change is also going to impose costs as militaries are forced to spend to fix things broken or damaged by changing weather patterns, shifts in water supply, and more:

Imagine rising sea-levels affecting China’s own installations in the South China Sea or Russia’s Arctic investments affected by increasingly unpredictable and extreme storms. It gets crazier when you think about the resurgence of resource conflict anxiety, not so much scarcity of oil & gas, but the concentration of production for rare metals and crucial military inputs in countries like China or the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The US accounted for 65% of global beryllium production last year, a small but crucial resource input for copper beryllium used to save weight in jet fighters, tanks, electronics system, everything you can think of that might be needed by a contemporary military. Beryllium is tiny in comparison to the volume of demand for copper, nickel, cement, cobalt, and more generated by the military.

I don’t have any inspiring takeaway analytically. However, a renewed spending push in the US to increase its relative military capabilities against adversaries will be met with rising defense budgets in China, India, and Japan while Europe decides what role it wants to play and Russia figures out its budget. Those increases in demand will then support metals and minerals prices and, in a marginal way, fuel demand. Yet another thing to think about when playing the market or assessing political risks for prices and policy scenarios.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).