Top of the Pops

Just an update that nothing bad has happened regarding my Twitter account. It’s infinitely more stupid. I was using a VPN on my laptop, but not on my phone, and they flagged that. Since my US phone number was deactivated recently, I can’t receive the code I need to confirm my identity and reopen the account in full so I’m still waiting on tech support. Till then, we’ll always have Paris.

Looks both the IEA and OPEC are tweaking down their demand growth expectations for 2021, with lingering issues like the shameful and willful failure on the part of the US congress to pass relief in a timely and adequate fashion eating into demand recovery. Worth a quick snapshot of what demand ‘recovery’ looks like if it happens by 2022:

It’s incredibly difficult to take those who argue for recovery by 2022 (and even growth) seriously. Next year is the only year we’ll see a large jump in demand akin to what happened post-global financial crisis, but the end of support measures in numerous developed and developing economies will create a drag on whatever gains accompany the distribution of vaccines and easing of restrictions. Increases of demand in the range of 2 million bpd last took place in 2016, and it was demand outside of China that pushed annual figures that high without as strong a countervailing demand narrative for Europe, the US, and Japan. Unless growth rates are running hot globally coming out of 3-4Q next year, the demand bull story rests entirely on changing consumer behavior and the materialization of spending power without any readily identifiable source aside from vaccines magicking the economic pain away.

What’s going on?

The decision to shifts away from investment into high-emission extractive industries taken by New York State’s $226 billion pension fund, a similar initiative led by Net Zero Asset Managers bringing together firms managing $9 trillion in assets, and Blackrock’s (managing $7 trillion) notable statement that it would take more active part backing shareholder climate initiatives against boards of directors are spooking Russia Inc. per reporting from VTimes. Russian oil & gas companies risk losing foreign investors supporting their equity valuations and ability to raise capital if they don’t adopt more aggressive measures to move towards net zero emissions. Tatneft has set a 2050 net zero target, but after progress last year, its net emissions rose this year casting doubt on the solidity of its plans. The rest are playing catchup while foreign investors and asset managers are making it clear they’ll use their financial influence to demand improvements to match their minimum standards. This is going to be a huge test for Russia’s obsession with sovereignty. You can’t wall off the country to foreign capital if you want Russian firms to be competitive and to grow.

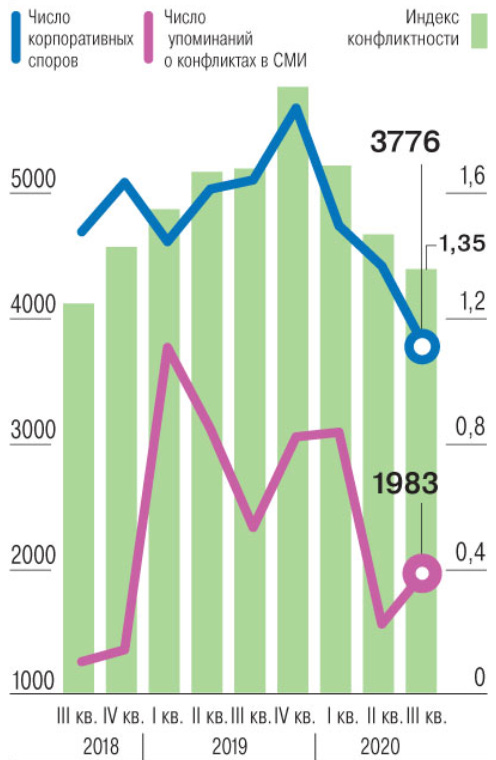

COVID has seen to a drop-off in business conflicts in Russia according to researchers at Skolkovo and the investment firm A1. But it’s not out of the goodness of business’ hearts that the last 3 quarters have seen a significant fall in legal fights and actions between companies:

Blue = number of corporate conflicts Purple = number of references to conflicts in the media Green = conflict index

The debt restructuring programs and moratoria on bankruptcies have delayed the chance for some firms to fight over assets, buyouts, and more. Conflicts continue in business centers like Moscow and St. Petersburg, but regions hardest hit by this year’s recession have seen much larger relative declines. 2021 might see a resurgence as state support is eased back and firms, fighting for share of a relatively stagnant market that does host some high-growth areas at risk of being run by oligopolies and monopolies, will have to get creative to increase revenues, profits, and profit margins. The question is how many will trust the courts to deliver.

Between March and November of this year, the number of Russians who consider themselves poor rose 6% from 27% to 33% according to polling from the Fund of Public Opinion. 1 in 3 Russians thinks they’re poor. 40% of respondents think that the poor have no chance to improve their material situation. Low pay, rising prices, and going onto one’s pension led the way for causes of poverty, with unemployment just behind. VTsIOM polling shows that 38% of Russians can only afford to buy clothing and food. When you look under the hood, it’s appallingly obvious that the people selling Russia as a growth story or economic success have no idea what’s actually happening behind the positive indicators available on a Bloomberg terminal. The data likely overstates the level of privation some since it refers to people’s self-conceptions of poverty or their social status, however it hints that Russia has become more like the United States and similar developed countries: highly unequal with stagnant wages, declining social mobility, and a need for a new economic settlement.

Putin’s appearance at the e-forum for United Russia’s volunteers yesterday has setup an important through-line for the Duma elections next fall. The volunteers — launched in March as an 80,000 strong ‘reaction’ force to address local problems — has reportedly responded to 1.5 million requests over the course of the year, and VTsIOM polling (always taken with a grain of salt) shows that 74% of Russians see them as really helping during the pandemic. It seems somewhat likely that the party will let one or more volunteers run for the Duma itself in order to try and offset the party’s image as a holding cell for handmaidens to power rather than a party actively representing the people. I’d watch to see that develop alongside the policy agenda laid out by “Green Alternative” and the continued need to resolve not just the municipal waste issue, but a variety of ecological problems that are no longer just social, but deeply economic questions about Russia in a global economy that’s now accelerating the energy transition.

COVID Status Report

Yesterday saw 26,689 new cases and 577 recorded deaths as the data now suggests the peak of the second wave may have finally arrived. Last week’s growth rate for infections fell to just 0.9%, which lends more credence to the idea that the dips in cases observed in Moscow and the regions are beginning to reflect an underlying trend and not just statistical noise:

Black = Moscow Red = Russia Blue = Russia w/o Moscow

Based on the political signals coming out of Moscow — including that United Russia event mentioned above — attention is finally turning towards what next year looks like and how to get through it. Otkrytiye’s Mikhail Zadornov gave a wide-ranging interview with RBK worth a look in which he describes himself as an economist in the minority for believing Russia can’t afford to provide direct cash transfers, but that its support measures were modest but effective (while making no mention of the non-energy commodity price rally that began towards the end of the first wave). Notably, he cites capital inflows from carry trades as the real driver of a strengthening ruble of late, a trend to watch as it’ll inflate equities and increase purchases of OFZs but doesn’t particularly correlate to “long money” being invested directly into actual production and can strengthen imports at a time when Russian policy really needs breakthroughs for import substitution and the development of new supply chains.

The Price ain’t Right

It’s a curious sight to see the complementarity (and some tension) between Russia’s macroeconomic orthodoxy — sound money, low external debt, and the painful lash of self-imposed austerity — and what I call its “bizarro Keynesians” — those individuals, institutions, and figures concerned primarily with price stability. The former group is well-established and known. The latter isn’t, and no, I’m not arguing that guys like Mishustin are whipping out data that aggregate demand is the key variable to ensure growth. Rather the opposite. Prices aren’t actually that stable and it is the role of the state to stabilize them. The latter group may be applying assumptions and principles more at home with Austrian economists, but they fully intend to make use of market management, both internally and externally, to achieve their aims in a manner that takes a more Keynesian view of the role and limits of the market as well as space for state intervention. It’s a balance, I argue, that will struggle to adapt to an energy transition that will simultaneously intensify the political incentives to pursue such a strategy without providing the adequate resources to escape the current account trap Russia’s now in thanks to 2 decades of suppressing domestic demand.

Mishustin’s order to stabilize the prices of socially significant staple goods is now taking effect, with initial agreements with sugar and sunflower oil producers already reached to control prices through 2021. 60 of the country’s biggest retailers have reportedly agreed to effectively function as a cartel and cap price changes, reducing their profit margins for the good of the nation. More will surely follow. MinPromTorg is adamant that stabilization measures won’t lead to shortages, a position with which I tend to agree. But this dynamic creates a catch-22. Wages fall, so the government scrambles to ensure price stability (assuming prices aren’t stickier than wages), which ends up reducing the level of investment made by the companies agreeing to said controls, which then reduces the business activity that ends up increasing efficiency, total output, and employment, which would help (limited by labor’s bargaining power obviously) trigger upward wage pressure. It’s not just that it’s a deflationary approach, but it kneecaps better balancing domestic production with domestic consumption. Managing the domestic market then interlocks into the massive pressure on Putin, Novak, and MinEnergo to sustain the OPEC+ cuts to balance the oil market.

Stabilizing prices, at least from the Soviet experience, entailed transferring the costs consumers should be paying given cost inflation for production onto the state budget via subsidy. Today, this effectively entails getting companies already earning a profit to take less, have less in hand to hire new workers, make acquisitions or investments etc., or else to use debt to finance activity until prices can rise again. This dynamic ends up undercutting one of the main focuses of the national goals: increasing labor productivity and the availability of high-productivity jobs. Using some Rosstat data:

There’s no evidence that ‘innovative’ economic activity is growing, high-productivity jobs have grown faster than labor productivity in percentage terms and you’d expect to see that figure be higher unless other Russians are being forced into lower-productivity work due to the effects of deflation/recession, and there’s zero change in the economy’s investment into technologies and associated techniques that would lead to major productivity improvement breakthroughs. This is where it gets interesting, and where the price stability regime now imposed to cap CPI for 2021 matters as a macroeconomic and political phenomenon that interacts with Russia’s oil & gas dependence and current account surplus. Here’s the OECD data on GDP per hour worked, with Russia set against the US, Germany, France, and United Kingdom for reference. Blue is Russia:

Between 2000 and 2019, Russia overtook the others for the amount of GDP per hour worked, which might also reflect labor’s greater share of national output compared to capital in countries like the US and UK. Thing is that the other indicators we have available suggests that this also reflects the relative increase of the extractive' sector’s share of the economy after 2014 as the recession hit services and consumption first. Price stability as a policy imperative in Russia works precisely because labor lacks the bargaining power to meaningfully raise its wages, and while wage growth in annual terms is fairly strong, it’s always come against the backdrop of high inflation till relatively recently, as well as the growing geographical inequality of costs of living and earnings. Wages in Moscow don’t necessarily keep pace with the housing bubble and so on. If you pull out energy and industry’s share of value added activity from the OECD data, Russia sees its own industry and energy sector shoot up to over 30% of all value-added activity in 2018, a 5% increase since 2011 when oil prices were over $100 a barrel on average. The income being generated by labor is too heavily pooled towards both physical labor and services that depend on extractives, and while some of that increase is quite likely a result of import substitution, it hasn’t translated into growth for the national income yet which leads me to suspect it’s more about who survives downturns. Stabilizing prices effectively entails capping investment into non-energy sectors, if indirectly and in this case to positive short-run effect to help consumption levels. All the while, the oil market is feeling a bit more bullish but knows that when OPEC+ eases in January, vaccine optimism and a late year Santa Rally won’t be enough, especially since the rollout and distribution of vaccines in non-China emerging markets will be differentiated and uneven compared to some developed market rollouts:

Many rightly dismiss fear-mongering over zombie firms in the middle of a crisis because it’s all hands on deck. Any fiscal stimulus and monetary policy support that keeps them alive is not to be ignored out of hand when tens of millions are losing their livelihoods and struggling to get through COVID. However, this combination of underinvestment into productivity, the (slight) narrowing of Russia’s economic base in terms of income generation, and now growing political pressures to transfer inflationary costs from consumers onto businesses is bound to nudge some firms, especially those with tight margins, into zombie territory. The traditional literature on zombie firms cites weak banks as a prime driver, as weakly capitalized banks start extending credits to long-standing customers indefinitely as they start to struggle and lose money and those companies become dependent if bankruptcy laws aren’t amenable to corporate restructuring. That undoubtedly is going to happen in Russia with a tighter current account surplus, though the data for zombie firms is skewed by the large presence of mining and oil & gas firms that took bets on upstream investments that were hurt by commodity price cycles. On the whole, becoming zombie isn’t a death knell and firms do recover, but are much likelier to fall back into only being able to service their liabilities, not growing, and investing less into physical and intangible assets. Global stats from the BIS:

Maintaining bank capitalization will require new sources of foreign currency earnings i.e. manufactured good exports as well as higher oil prices. As Russia’s markets have tended to concentrate into the hands of fewer firms since 2014, the risks posed by zombification worsen systemically. If Euro, dollar, and CNY receipts drop off significantly again for an extended period of time with oil prices jammed below $50 a barrel, the pressure rises for Russia to more strictly adhere to production cuts which, at the same time, hinder intermediate demand and services demand, space to grow wages, and attempts to ward off zombification. If wage growth doesn’t resume, then suddenly the cabinet is tasked with price stability as a political directive for the long-term, even if they don’t necessarily use informal cartel agreements with different sectors to achieve it. If the CBR and Russia’s economic policymaking apparatus is truly concerned with price stability, you’d think they’d worry more about improving the utilization of Russia’s real resources, productivity, and infrastructure investment. Instead, they’ve forced themselves into a position where to rein in inflation, they have to engage in an expansion of market managing mechanisms domestically while locking themselves into a partnership with Saudi Arabia on the oil market that, despite reports to the contrary, is probably more sustainable for Riyadh than Moscow. Prices aren’t stickier in Russia because of structural failings, such as the high degree of seasonality or annual variability for shipping capacity and costs. A little dose of Keynesianism wouldn’t hurt the recovery next year.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).