Top of the Pops

In the Vtimes, BCG’s Anton Kosach wrote up the risks posed by an EU carbon border adjustment tax that could come into effect as early as the end of 2021, estimating that it would cost Russian exporters $3-4.8 billion. That’s a soft estimate given that the European Commission and EU governments are going to start building carbon emissions into trade disputes on competitiveness that’ll impose other kinds of costs. Crucially, however, Kosach notes that the adjustment tax would raise production costs per barrel of oil by $2. That’s a big enough gap with Saudi Aramco to see Riyadh lord it over them while much more rapidly deploying best-in-class tech and techniques to minimize emissions.

As expected, COVID-19 has become a political cadre risk:

The daily caseload has exceeded 18,000. Consumer research shows that 20% of Russians are starting to load up on essential items in advance of a potential lockdown despite assurances from Putin it isn’t coming. Watch the CBR reports for signs of short-run inflation.

What’s going on?

Rostec and Rotelekom have set a target of 50 million 5G users in Russia by 2030. The road map they’re currently finishing aims to have 200,000 users by the end of 2023 and 5 million by the end of 2024. Settling issues with the auction remains a big impediment as 5G operators currently can only use frequencies above 5 GHz rather than the ideal range of 3.4-3.8 GHz, which raises costs for operators. Assuming that issue is resolved, the plan seems realistic. Still, I’d expect adoption to take place at a faster clip on other developed markets without the same hullaballoo once businesses boot up their spending cycles and have clarity on investment horizons after this year.

In a clear sign of growing stress on the nation’s medical output, spending on medications in pharmacies through September is up over 10% compared to 2019 while the volume of purchases is down by a little over 5%:

Title: Medication sales in pharmacies, sales in monetary terms, mln ruble

Some of this would be wipeout by currency devaluation, but with Russians slowly moving back into stockpiling mode, this is a trend to watch. Attempts to fix the domestic market and replace imports have been met with some success, but price fixing continues to undermine proper investment into production, and to trigger shadow inflation or underreported inflation via relative shortages.

In Moscow, 14-18% of all office space - approximately 250-332,000 sq. meters - in key business districts are emptying out now. The worst damage comes in Moscow-City. Given the lack of office space across the city, the space won’t go empty for long, but if Moscow is any indicator, that kind of churn in other major cities that lack the same magnetic pull on the labor force is going to decimate small and medium-sized businesses while larger ones will be able to snap up more space for cheaper. Realistically, whatever the recovery ends up looking like, it’s going to be uneven. Moscow will come out ahead as it always does, while regional cities struggle. Some companies also seem likely to try and sublet given cashflow struggles. Imagine the litigation to come…

Minprirody still hasn’t found an adequate way to ensure producers’ are held responsible for ecological damage from waste. Part of the policy fight now comes from creating adjusted rules and regulations to define who is actually a manufacturer. The way the debate is now framed is designed to benefit the extractive sector by leaving them out of potential waste, and only targeting the firms making products out of their inputs. That’s not sustainable, and the lack of definition as to who a manufacturer/producer actually is renders enforcement haphazard and ineffective. The regime is simply not paying attention to the issue area that launched the most widespread protests in 2019.

Shale Satan!

If Igor Sechin is right and American shale oil production has stolen Russian market share over the course of OPEC+, it’s worth assessing what exactly COVID-19 has done to it. Breakevens are well and good, but don’t properly capture the business rationale for anyone fracking a well. Going back to the Q1 survey of shale oil producers from the Dallas Fed, note what they have to say about operations if oil prices hover around $40 a barrel for an extended period of time. Thanks to Mason Hamilton for the grab:

West Texas Intermediate is now down to around $36 a dollar, and note that the balance of answers for these firms will have undoubtedly shifted some as cashflows have been crimped this year. The plurality at 4+ years, however, suggests a few things. Companies have had an easy time accessing longer-maturity junk debt or investment grade debt issuances and that average debt yields below investment grade were just above 5% come February having last peaked at just under 8% at the end fo 2018. The firms likeliest to go under within 2 years probably issued their debts earlier, faced higher relative yields, are less efficient operators, or else raced to issue debt early on in the current crisis and faced higher rates before the Fed reined them in. The bigger issue is that the investment horizon for shale is radically different from a conventional oilfield where a company is sinking money in for decades:

You’ve basically tapped any given well within a month and a half. So each well being fracked is facing a production cycle of 6-7ish weeks, many of these wells were already drilled and abandoned so the sunk costs aren’t as high around exploration, and that also means that you have existing infrastructure in place that can be used or refurbished. These factors help capture a shift that the World Bank noted in its October commodities report:

As you can see post-2014, oil lacked a medium-term price correction cycle since Saudi Arabia could no longer effectively manage production levels against marginal demand increases. Shale drillers loaded junk debt would pile in hoping to realize returns. I’ve already pulled from it before, but the Equinor post-mortem on the $20+ billion it lost on US shale has some useful visualizations for how consolidation in the space, the underlying trend pre-COVID, is going to accelerate and define what comes next:

If you think of the oil market in terms of financial balances, impairments, reversals, and debt issuances rise in the United States when production cuts in OPEC+ fail to lift oil prices or, as is now the case, the demand-side gets creamed. The first two represent foregone future revenues and losses today and debt corresponds to an expected present or future cashflow to finance the capital now in hand, presumably for capital or operational expenditures. What you also see is a significant decline in organic Capex after 2010 over the same period of time that tax breaks in Russia begin to account for more and more of Russian firms’ earnings and ruble depreciation against the dollar absorbed potential cost increases.

The problem now is that there aren’t as many cost-cutting opportunities to be had. So in effect, the biggest companies with lower debt servicing costs and, ideally, a more diversified revenue base i.e. owners of midstream assets like pipelines and wholesale distribution and downstream assets like refining capacity or gas stations can make moves to acquire acreage and smaller operators now flailing. Conoco just forked over. $9.7 billion to acquire Concho making it the largest independent oil & gas company in the United States and a massive player in shale. Conoco’s now worth over $60 billion. Chevron picked up Noble Energy, Devon Energy is buying WPX Energy, Pioneer is buying Parsley Energy, and so on. At large, the industry is pivoting from production to improving returns, even if that means settling for less output in the years to come because of lower prices. It’s also worth considering that the current price environment could privilege firms that aren’t publicly-traded insofar as they can adopt slightly longer-term planning strategies given investors are sweating bullets over oil major equity performance this year:

Malcom Tucker, the sweary comms chief protagonist of The Thick of It, goes down in a blaze of glory at an inquiry over his illegal access to a private citizen’s personal details by pointing out that everyone in politics leaks and the inquirers are aware that they “can’t handcuff a country.” He’s just a fall guy. When it comes to shale, there is no “killing” it. It’s only a fall guy for what’s gone wrong with the oil market, namely its missing medium-term price cycle. Arguments to that effect that it can be killed are akin to suggesting that the Saudis and Russians can destroy a technique for oil extraction. It makes no sense.

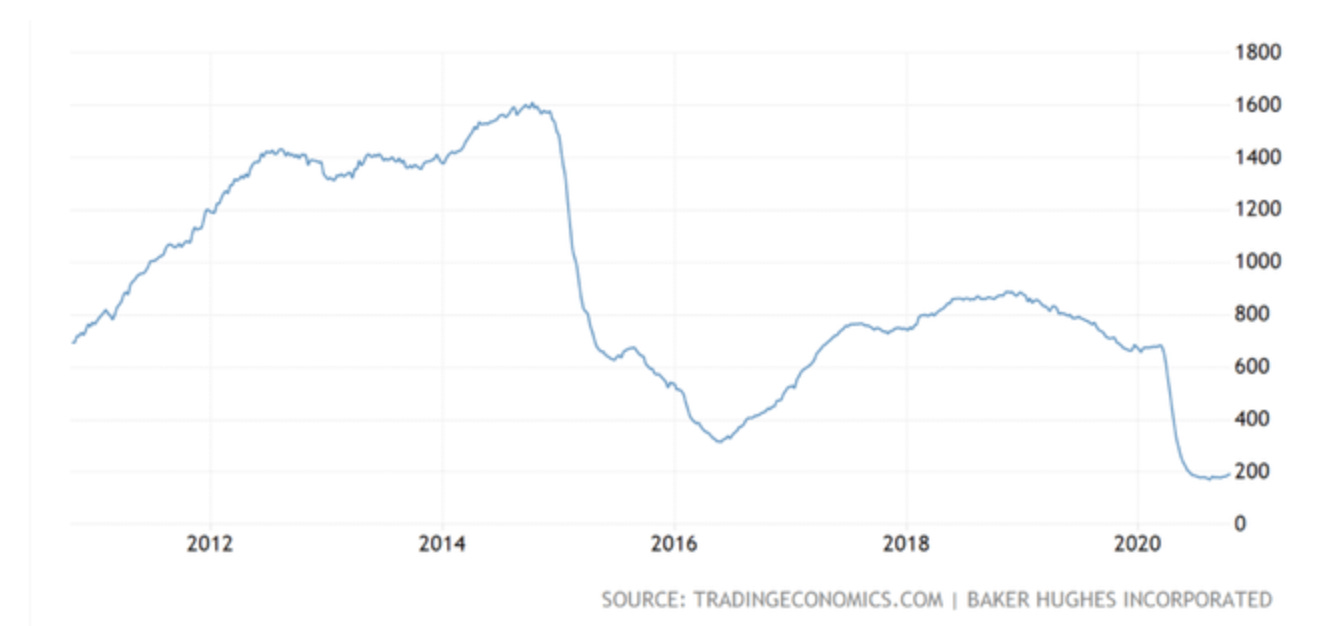

Declining counts for oil rigs began in 2019, affected by declining quality of the acreage being drilled, well exhaustion, slowing demand growth, efficiency gains, and Wall Street’s exhaustion. It’s really about finance.

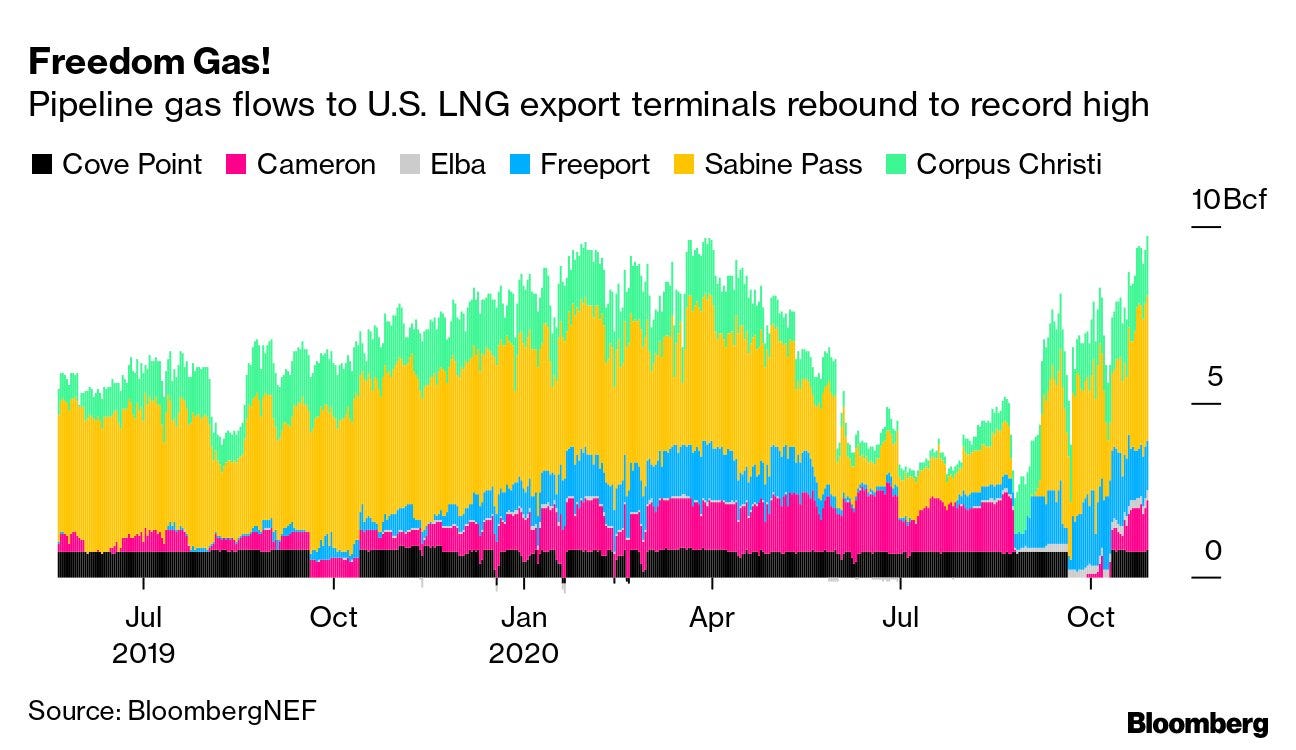

Deloitte estimated potential asset writedowns and impairments worth a whopping $300 billion for shale earlier this year, over 15% of Russia’s nominal GDP. But even with those writedowns, there are companies that will be left standing because of low borrowing costs. Shale is crowded with corporate zombies that make enough to survive. Igor Sechin’s now pushing the line that green new deals and western energy plans threaten an investment imbalance that will lead prices to shoot up again. Well, if he wanted to kill shale so bad, he might consider that while the bigger and smarter players ride it out and strong LNG exports from the US to continue - they will no matter who wins the election - then you need shale output to rise again. Rystad’s optimistically arguing an increase to $60 a barrel would trigger a new wave of production growth. I’m a little more cautious in my outlook, but if demand has now been dented structurally, then the price war earlier this year has proven how fruitless trying to wreck shale - again, a technique for production that has short-term financial incentives and business models now being incorporated into larger, diversified firms - has been. And unlike Russia, tax regimes in the US are stable. Texas has maintained a 4.6% oil production tax for decades, a relatively stable marginal effective tax rate just under 30%, and the latest hit to the industry is likely to trigger some new jockeying in the statehouse to offer forms of stimulus support to get production tax revenues up again given prodigious revenue growth over the last decade. From A Field Guide to the Taxes of Texas (link was broken, but should be readily searchable on Google):

Russia’s oil sector is never going to overpower US oil production, nor will Saudi Arabia. To truly do so now would wreck their economies and create a supply overhang it would take years to unwind. In the mean time, US firms would wait. Near-zero interest rates are here to stay in the new monetary normal, junk debt will be relatively cheap to issue, and companies are now innovating as to how they can incorporate shale into a broader portfolio that still generates adequate returns. Add in that demand for natural gas has more room to grow on developing markets and shale offers associated volumes and pure natural gas plays, and you have yet more reason companies aren’t giving up the ghost on this thing. The patch is back at it for LNG from the Gulf already:

Monetary policy shapes real resource constraints when it comes to shale (take that Milton Friedman!). The Fed is happy to pump away and keep feeding the living and walking dead, while Russia’s own fiscal reticence undermines future production growth even without the OPEC+ deal in place. Whatever future oil & gas have, US shale will be a part of it, disrupting the medium-term price cycle so that the industry throttles between forced production restraint and political fights over who gets their “quota” or piece of a production increase. C’est la vie.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).