Top of the Pops

Brent futures have climbed to nearly $70 a barrel as US stockpiles have declined thanks to the ‘Biden boom.’ Declining gasoline and distillate inventories reflect the surge in goods demand and slow return to normalcy. Rising prices are good news for the budget, but aren’t yet providing much growth stimulus — some will come from rising output, but that’s still limited. If rising oil rents are converted into demand support, however, that might help manage the economy-wide tightening of credit conditions coming before the consumer recovery has really taken root:

Top - tightening conditions Bottom - easing conditions Light Blue = big biz Yellow = mortgages Red = SMEs Green = consumer credit

The tightening is coming just as consumers are burning through savings, SMEs are facing increased bankruptcy risks as protections have ended (bankruptcy data will be delayed by the time it takes the courts to move through legal proceedings), and even bigger businesses face rising borrowing costs. The single biggest problem for investment levels is that large firms are increasingly relying on profits to finance investment — in practice, that means sitting on rents they accumulate, which ends up reducing productive investment, productivity gains, and growth. Rising oil prices are also poking at domestic inflation levels. Benzine prices have been controlled through a reformulated domestic pricing system that will cost the budget 350 billion rubles ($4.68 billion) to refiners and oil companies up to 2023. Russia’s ‘decoupling’ from oil has left in the worst possible position — high prices don’t strengthen the ruble, don’t increase growth, minimally raise industrial and services demand, and increase inflation while low prices strain the budget, depress demand, and worsen stagnation.

What’s going on?

Tourism was supposed to provide a jolt to Russia’s efforts to increase non-resource export earnings, in this case by easing visa rules and bringing in more foreigners. But the sector’s facing a large shock from the approaches taken to save businesses without saving demand — the number of tour agents fell by 6% in the last 6 months along with a 4% decline in the number of hotels and a 3.3% fall in tour operators. Those numbers hide the true extent of the damage. In the last year, 35-40% of operators have gone under, with the worst losses realized in Moscow and St. Petersburg since they were the most reliant on international travel. In both, the number of agencies (not tour operators) has dropped 8% and 10% respectively. Regional declines are, generally, worse than in Moscow and St. Petersburg since the delights of Khanty-Mansiysk don’t draw the same domestic interest as the county’s two biggest cities. But this data also reflects loans to maintain employment, moratoria on bankruptcies and debt collection, and other maneuvers that preserve value on balance sheets until the cash flows come back. There’s not much evidence Russians are going to be able to spend at 2019 levels again this year, which means a continued decline in the overall size of the market unless operators further slash margins and lower rates. Some of this stuff will improve with the willingness to streamline the visa process, especially for shorter tourist visits, but the longer that Russia lags the West in vaccine take-up, the less likely that western tourists come back even if fully vaccinated until they feel more confident. Obviously there’s a much larger pool to draw from and there’s been a focused effort to try and improve Moscow and St. Petersburg’s ability to host tourists from China and Asia more broadly (where possible). The sector’s otherwise decent growth potential is taking a big hit from the domestic response.

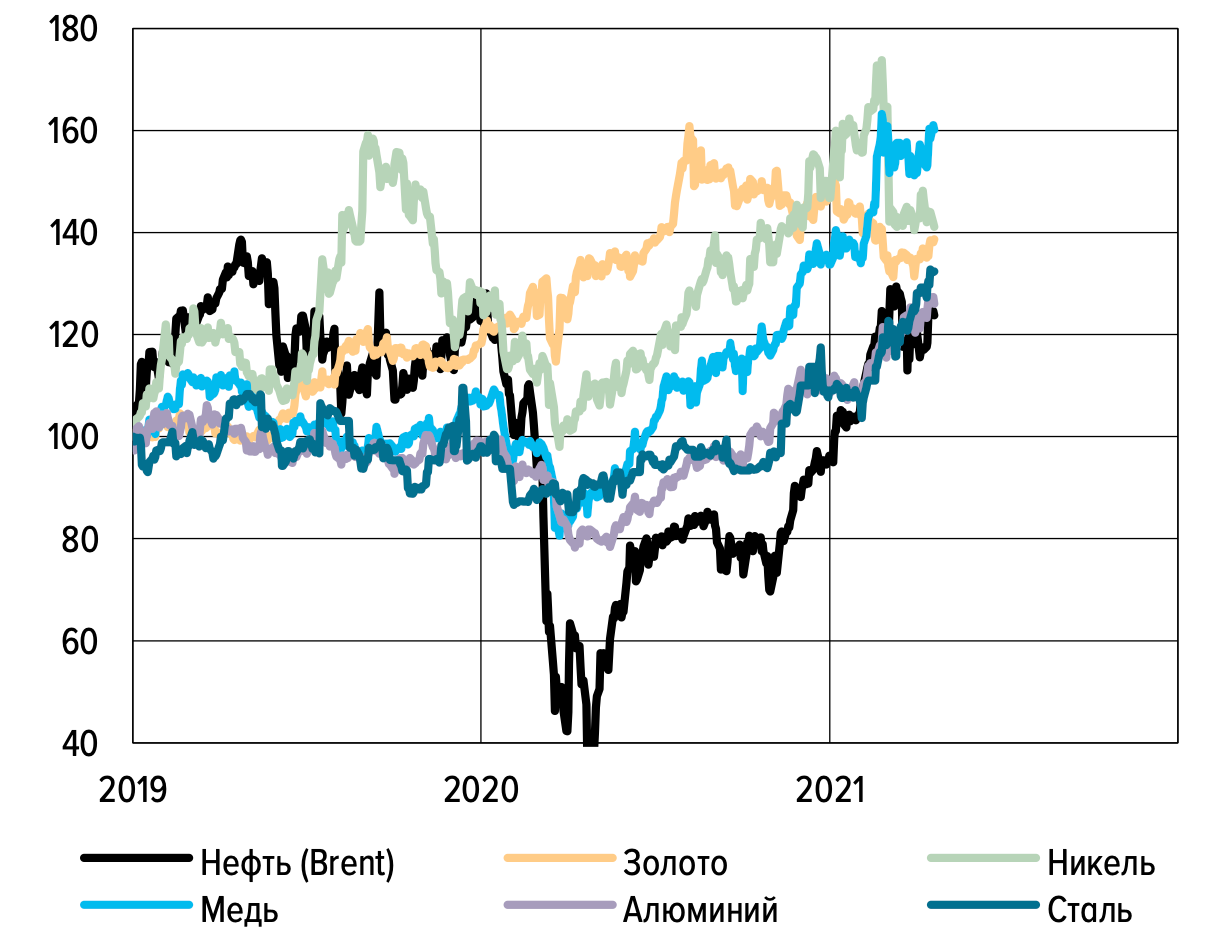

Despite the earlier doubts that a commodity super cycle was emerging, the rising prices of a broad basket of commodities — Brent crude spot prices are on their way in pursuit of futures threatening to break the psychological barrier of $70 a barrel — are clearly following global economic recovery. The result is a more substantial claim that we’re entering a new cycle for a variety of reasons. Metals & minerals production in particular will have to keep pace with a demand squeeze stemming from the energy transition. The MSCI index tells the story:

It’s everything. Corn’s now at $7 a bushel for the first time in 8 years. Copper’s above $11,000 a ton for the first time since 2011. Lithium carbonate is up 100+% in price and cobalt is up 40%. The cycle is here, and any additional US stimulus measures will boost demand levels further. Normally a commodity boom would be a good thing for a commodity exporter like Russia, but oil can’t climb too much more without a significant increase in investment into production in the US and elsewhere outside of OPEC/Russia. Add to that the increasing competitiveness of EVs and hybrids on a price basis and the relative price ceiling for oil that will encourage fuel switching is dropping. Metals & minerals can’t generate the same level of rents to redistribute as oil for Russia, and resource extraction is precisely the wrong sector to increase investment levels into because it further concentrates labor, capital, and state support in low-value exports, reinforcing the current account fixation that has ruined Russian economic policy since 1999. There aren’t enough savings from households, businesses often can’t invest well what they do save, and the refusal to use deficit spending to generate more domestic demand means that manufacturers have little reason to expand capacity for value-added production to support diversification efforts. It’s the worst possible moment to see a super cycle, even a mini one, take deeper root for the regime since the Central Bank has managed inflation since 2014 via real economy deflation in the form of falling incomes as much as the brilliance of Russian bankers. This isn’t the 2000s again, but at least on the mining side, I don’t think the market quite appreciates just how much production will have to increase to make the world ‘green’ as the market moves that direction (300+% surges in demand for physical inputs in some cases).

The Central Bank’s latest report on monetary policy from 1Q shows that Nabiullina’s team are on course to ‘normalize’ policy and keep raising rates till they fall into the 6+% range in hopes of taming the worst part of the current inflationary surge. A lot of the price increases are linked to pro-inflationary factors, including global price levels and a weaker ruble per the report’s logic. Notably, Russia is hiking faster than some of its primary ‘peer’ EM counterparts like Mexico or Indonesia and India. My assumption is that the Bank wants to control capital outflow while calibrating the pace of increases to avoid a domestic adjustment cliff throwing consumption into chaos by affecting financing and refinancing. Capital flows into emerging market debt and security markets recovered — they were just $10.1 billion in March and rose to $45.5 billion in April. The CBR also confirms my suspicions about export price levels are really the story for the Russian recovery:

Black = oil Yellow = gold Green = nickel Blue = copper Purple/Grey = aluminum Dark Blue = steel

I’ll pull more from it for today’s column (realistically), but bottomline is that the rate hikes will only accelerate faster than the current drip feed of adjustments if a real recovery is observed. They know they risk choking recovery by moving too fast. Unfortunately they don’t have any fiscal partner to tackle the current crisis. All the proposals floating around Mishustin are ineffective and tackle the wrong problems.

It can’t be stressed enough how bad it is that Russians are burning through about 7 billion rubles ($93.73 million) in savings a day to cover rising costs and expenses, some of which may reflect a spurt of new consumption but most of which is probably going to basics. Wages at SMEs are down 17%. It’s the state firms and biggest corporates holding back a further income collapse. The consumption recovery taking place is actually reflecting fears that consumers will face higher prices the longer they wait since their savings are devaluing as inflation keeps rising. In 1Q, an average of 13.5 billion rubles ($180.63 million) in loans were taken out by individuals daily to finance consumption. Net personal debt is equivalent to 18.7% of incomes, a record high. If we compare what’s happening in Russia to the US, a consumer economy, it’s reversed. Whereas US demand-side support and stimulus efforts allowed households to collectively deleverage further (a process that had begun years prior to COVID), Russia’s supply-side approach coupled with budget consolidation has forced households to keep borrowing and borrowing. How exactly MinEkonomiki intends to achieve 3% real income growth for the year after seeing a 3.6% fall in 1Q and record levels of indebtedness is beyond me, and it’s no wonder Reshetnikov just wants to fiddle with the numbers instead of doing anything. Fiscal stimulus now would actually still be countercyclical for households insofar as the firms now recovering in the business cycle are exporters and the domestic recovery is far, far weaker and reliant on debt held by families and individuals whose incomes are still falling. Fiscal policy is the only way out of the dead end Moscow’s dug for the rest of the country.

COVID Status Report

There were 7,975 new cases and 360 deaths recorded by the Operational Staff. There’s been a 10% rise in the number of patients coming into hospitals for COVID in Kazan’ over the last 10 days. Oddly little else out there from the usual keyword searches, but it’s an important indicator that a major non-Moscow city other than Piter is seeing a slow but steady rise in the hospital load. Rospotrebnadzor is doing some messaging work trying to ensure everyone understands they need both doses and nudge vaccinations along. The data here is imperfect given competing announcements in Russia, but Russia’s vaccination campaign is basically on the same track with India’s, where the death toll has surged past 3,500 daily:

The Central Bank is holding out for the possibility of a 3rd wave posing serious economic disruptions, mediated by the demand recoveries in the US, China, and the improving situation in the EU helping exporters. As more cities announce rising hospital loads, a 3rd wave will be more apparent.

What we talk about when we talk about sanctions

A new report from the Atlantic Council on the effect of sanctions on the Russian economy trots out the greatest hits: sanctions stopped Russia from seizing Ukraine in 2014, have somehow reduced annual GDP growth by 2.5-3% a year, have killed any future growth, and have a greater impact than previously understood. From about 2017-2019, I was highly skeptical that the sanctions themselves were having a large impact, went through a period where I thought their financial impact was significant, and then finally came around to my current thinking — they’ve had a big impact, but because of the policy choices made in Moscow more than the concrete effects of sanctions themselves, with a few salient exceptions. Reading this report now, it’s clearly a piece of political analysis with an economic component that serves a political argument: Russia is reckless, dangerous, must be stopped, yet has been stopped by sanctions. This is the type of stuff you’d have seen back in 2016 or 2017 in order to cow the Obama and then Trump administrations into action. Now that congress has filled that gap and the US continues to tighten the sanctions pressures, it’s unclear what’s really being accomplished.

The report posits four observable effects of sanctions: forced deleveraging, reduced FDI, strong capital outflows, and cautious government macroeconomic policy. According to the authors, the first 3 can’t be derived from oil prices. It then maps these effects onto the fiscal channel within the economy, the balance of payments, and balance sheet channel. From the get-go, the authors argue that the reduction of foreign debt — $729 billion at the end of 2013 down to $470 billion by the end of 2020 — posed a problem because it denied Russia financial resources useful for its development. The core claim made is that the entirety of the foreign credit held that has been drawn down could have gone towards economic development. That’s a drastic simplification of the role that debt plays, the need for foreign finance in a country that runs a large current account surplus, and what development would look like. What’s even more bizarre is that no mention was made of how the oil price and policy decisions taken in 2014-2015 influence that calculus but were a result of political preferences more than sanctions. The following LHS is US$ blns and RHS is US$/bbl:

It beggars belief that the oil price didn’t have a large impact on FDI flows since it had always been the primary recipient of FDI in the country, and most importantly, was on the cusp of receiving tens of billions of dollars of upstream investment in the Arctic that sanctions disrupted but would have vanished anyway because they required oil prices at $100/bbl to sustain. Consumer industrials were never formally sanctioned and because of Russia’s large current account surplus, there’s always money available for productive investments domestically. The issue wasn’t sanctions holding that back, it was the macroeconomic orthodoxy and path dependence of the relative underinvestment across the economy prior to 2013 resulting from the political consensus around the management of Russia’s petro-wealth, currency, and economy more broadly. The FDI levels pre-sanctions reflected both oil prices and the consumer growth they were able to sustain till 2013. What’s more, it’s mostly state-owned or state adjacent large firms borrowing from abroad, and they’re backed by the sovereign. Foreign loans never financed much business activity and there’s another important change for foreign borrowing post-Crimea — the move to a floating exchange rate introduced currency risks. The investment challenge reflects a lot of other factors:

Red = investment in fixed assets Blue = production of investment goods Grey = train transport of construction goods Yellow (RHS) = import of machines and equipment

The reality is that the over-concentration of investment into resource extraction (and now import substitution) means that investment is effectively a function of the state of the current account and fiscal regimes for resources.

The claim that sanctions forced firms to deleverage deserves some nuance. There’s no doubt that capital outflows surged as foreign investors pulled money out due to geopolitical uncertainty, but the Central Bank and sovereign wealth funds that have since been merged into the National Welfare Fund (NWF) held enough reserves to cover the private sector’s outstanding obligations that were maturing. The issue was the ruble’s managed rate. The transition to a floating regime reduced the salience of Central Bank reserves managing currency risks — the reserves held by the regime were meant to prevent bank sector crisis (it happened) and ensure foreign creditors saw the state as solvent, allowing Russia to continue to use its domestic bond market to draw in foreign capital. The Central Bank’s massive interest rate hike should have been enough to keep capital in banks, however, and reduced the pressure on foreign reserves, though Russians also race to USD when crises hit. The deleveraging definitely came in response to sanctions immediately, but Russian authorities made conscious choices to curb the spike in inflation and surge of foreign currency demand using austerity measures in sync with very tight monetary policy. The former became a necessity because of the latter, but could have been eased after the initial inflationary wave to increase investment levels across the economy. As usual, the analysis rejects the agency of Russian policymakers to adapt in a more effective fashion to the sanctions regime, overstates their dependence on foreign finance, and also ignores what’s actually happening on balance sheets. Not only is a large share of the foreign investment they point to roundtrip investment from Russian investors, but Russia’s still a capital exporter. There isn’t a shortage of money for investment (though there is a declining pool of savings from households). The business environment and monetary straitjacket on fiscal policy kill investment. You need more demand.

Finally, the authors assume that since the goal of sanctions was to force Russia to leave Donbas and Crimea, they’ve failed. So they’re having a huge impact robbing Russia of growth but also failing to achieve a security aim. This makes little coherent sense for critical purposes, but raises the larger point of where I’ve come down in understanding the efficacy of western sanctions. Ever since they were applied in 2014, sanctions have strengthened the most economically destructive impulses, assumptions, and incentives within the political economy of Putinism. The refusal to use fiscal spending to increase demand and raise living standards leaves businesses only one option to achieve real growth: bearhug the state. That means seeking trade protections that inevitably worsen domestic inflation and raise producer costs, subsidies, regulatory rents, legally-mandated monopolies or oligopolies, and whatever else they can scrape. If sanctions are intended to degrade the economic capabilities of a competitor state over time, they’ve achieved this not because of their direct economic effects, but their political ones. The decline in living standards is a time bomb and is already crimping the Kremlin’s ability to more actively pursue foreign policy aims because of bandwidth limitations. The more firefighting you have to do domestically in government, the harder it is to coordinate activities when institutions are so frequently incentivized to craft policy as a means of extracting rents.

If we follow the authors’ logic, the kleptocrats are the system’s weakest link. Sanction them and their London homes and Miami flats and kids going to boarding schools and they’ll turn on the regime. I fully agree that they’re the weakest link. I just think attacking them misses the point. Policy is now securitized and anyone close to power with wealth is aware they have to prove their loyalty in what has become an increasingly ideological dividing line between Moscow and the West. If the kleptocrats leave the country, getting them to turn is irrelevant. Their assets will be seized and handed over to a less competent manager who’ll prevent the worst from happening. The real crisis is the absence of growth and expansion of resource-led rentierism into an all-encompassing hunt for rents among import-substituting industries and domestic lobbies while Russians’ buying power continues to fall. Systemic collapse happens when the system can no longer buy enough loyalty from enough people, not when the disloyal billionaires move abroad and lose their Russian assets. One can claim western sanctions have been successful because they’ve degraded state capabilities, though the case for their relevance in Donbas in 2014 is spurious at best and has never been supported by empirical evidence. One can’t claim they can work without hurting the Russian public. Politics since 2014 have borne out that reality. Most importantly, accelerating the energy transition and redevelopment of semiconductor industrial capacity in the US and EU are far more effective threats to the regime than further sanctions, even if they’re warranted in targeted fashion. These debates about the efficacy of sanctions are exhausting because of the manner in which they’re politicized. Sanctions work. Sanctions don’t work. In Russia, as usual, most of the pain is self-inflicted, even if sanctions offer an extra push.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).