Top of the Pops

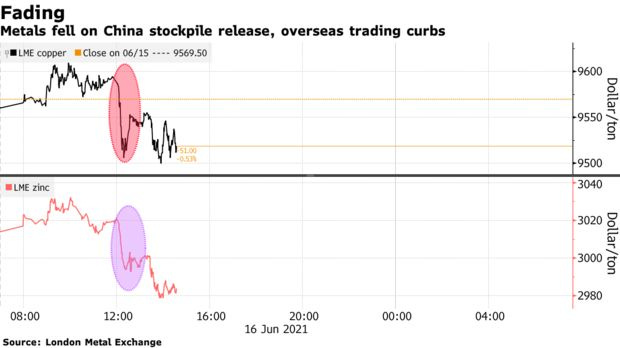

The New Statesman offered a nice writeup of the state of the broader turn against neoliberalism now taking place in Western governments and among western economists, activists, and anyone seeking desperately needed reforms and action. Anton Siluanov’s “childish diseases of leftism” are, in fact, an historical return to the consensus that the state has a pro-active, positive, and crucial role to play not just shaping markets, but guiding them and making them. China offers a useful example as it’s begun to sell strategic reserves of commodities and ordered firms to reduce their exposure to foreign commodities so they can tame price inflation. This from yesterday shows the immediate impact on key metals contracts on the London Metals Exchange (LME):

Maintaining strategic stockpiles of commodities was commonplace across the OECD until they began to be unwound heading into the 70s as the consensus around planning waned, and arguably the inflationary explosion led by oil prices would have been better managed had more states maintained a strong role as a strategic consumer and seller through the ‘crisis’ years (along with a host of other policy choices of course). Russia has a version of this, but it’s a rent-providing institution with little use. But we’re at an interesting moment where the ideological priors of privatization leading to growth are now suspect without an activist state supporting growth. The coalition of voting and asset-owning interests either invested in the neoliberal status quo or else lacking faith in any alternatives presented by political parties remain potent despite what’s becoming a clearer intellectual turn. The irony is that the state capitalist model now exemplified by China could have become a positive guide in Russia as well had it not been swallowed alive by the contradictions and pitfalls of a resource export-led growth model that has to generate an expanding array of rents to secure the regime’s political base of support. This still-forming “national capitalism” heralds the rebirth of active industrial and trade policy in the West, buttressed by a strong fiscal state and slow revival of Keynesian (rather than Neo-Keynesian) thought. Back in January, CSIS put out a report showing that the US is woefully unprepared for a necessary surge in military-industrial capacity in the event of a Great Power war — core to the expansion of the state’s planning and directive capacities over a century ago during WW1. Russia is surely just unprepared, if not more so because doing so would trigger a much higher level of domestic inflation without the same fiscal strength. Planning is back. If only Moscow could plan.

What’s going on?

The Duma has voted to allow Roskomnadzor to access subscriber/user data from telecoms operators in an obvious blow to privacy and related legal institutional arrangements in Russia. The new bill targets socially significant sites managed by domestic operators and the issue of “grey” simcards being used. The bill mandates operators provide the regulatory authorities with information about any and all subscribers and users paying fees, including the location of the base station their phone connection is routed through, and the date and time stamps for when they receive calls, texts, or video. The new law comes today as I’ve had trouble accessing Kommersant and finanz.ru reliably the last few days and have heard others complain about outages with state sites. There’s clearly a new push underway to sort out the management of the internet and to provide Mishustin and the new managers better tools to identify and aggregate data on dissent at the same time the security apparatus wants to be identify who to intimidate, arrest, or investigate. This after a proposal to more strictly regulate access to pornography and create a single state-owned platform for video streaming, though the details are a bit vague. Any operator linked to networks abroad has to ensure that the physical infrastructure connected to foreign countries is owned by a Russian entity that is registered on yet another special list. The authorities are moving fast to clamp down on the space to communicate without the state being able to find out. Innovation requires safety and legal security. This bill will strangle both over time.

The government is responding to the current spike in benzine prices by re-instituting price control measures last used in 2018 via the ‘damping’ mechanism put in place with the oil tax maneuver. In the last half year, the retail cost of Ai-92 fuel has risen 20.8% and Ai-95 has risen 27.5% while their respective wholesale prices have risen 6% and 7%. Vertically-integrated oil companies and independent refiners are now set to receive an additional 350 billion rubles ($4.82 billion) in budget support for 2021-2023 to pay them to keep prices down. It’s the Soviet price control system maintained — subsidize the producers to avoid passing on costs to consumers. As we can see, the oil sector isn’t doing great financially right now amid the combined price recovery and slow unwinding of production cuts that have capped upstream investment:

The LHS is financial inflows into the sector and the RHS is outflows. The balance sheet costs for oil firms will be absorbed by the budget to save consumers. It’s a convoluted set of measures that’ll hopefully help poorer Russians, but is highly subject to a production recovery.

Vedomosti interviewed the head of the Avtodor consortium Vyacheslav Petushenko about the state of the biggest road projects in Russia, and the interview had some useful tidbits about the way Russia operates and what goes unsaid regarding infrastructure development. First off, the highway between Moscow and Kazan’ now under construction is going to be maintained using operator fees. We’d expect that given the Platon system and it isn’t necessarily bad, but what matters here is that this highway — not the strongest candidate for a growth-generating project that more likely keeps the authorities in Tatarstan happy but is useful — has to be paid via user fees. Authorities are acting as though they’re cash-strapped. That trickles down to these projects, whose costs are passed on to users and consumers, creating an ouroboros of weak demand and distances undermining returns incentivizing the state to find yet more ways to charge for use, which still offers weak returns rather than just letting the state bear all the costs. Petushenko openly notes that the rise in bitumen and metals prices has created political pressure for Avtodor to find ways to cut costs at a time when state contractors who locked their prices in last year are getting screwed by inflation. The road from Dzhugba to Sochi — estimated to cost 1.5 trillion rubles ($20.67 billion) — can’t babe fully funded at present and that’s a huge rent-machine of a project.

Telecoms operators led by ‘Er-Telekom Holding’ are now asking the government to extend tax write-offs to cover investments made into digital infrastructure — broadband cellular networks, data process centers, and more. The proposal calls for the tax breaks to apply to any type of investment regardless of type of equipment or level of complexity with the sum of money invested taken off the final tax bill rather than the tax base. One of the biggest problems with Russia’s reassertion of industrial policy after 2013 has been that it’s often created incentives for more advanced investment and development that mostly exist on paper. If your basic infrastructure is inadequate, you don’t suddenly leapfrog to an investment renaissance. Reducing firms’ tax burden based on their investment activity could allow them to build 10-15% more than currently planned based on existing budget levels. That’s a decent improvement without spending any more federal money. As always, there’s a hilarious security catch. The security establishment and government still want Russian telecoms operators to use the 4.8-4.99 GHz band for the national 5G grid. But operating costs are higher at that frequency despite being “safer” for military purposes — there’s competition over different frequency bands and concerns about standards in NATO countries and militaries vs. Russia. Though AKRA estimates investment plans for 2021-2027 will cost the sector 1-1.1 trillion rubles ($13.79-15.17 billion), the frequency standards will elevate costs. The bill for cities of over 1 million people through 2030 will be 723.3 billion rubles ($9.98 billion) alone and take 20 years to pay for itself. The economics are even worse the smaller the market across a larger territory. Tax breaks can’t resolve this problem. A better fiscal system and framework supporting demand can do a great deal more, though geography imposes costs in Russia few economies have to manage at such a scale.

COVID Status Report

14,057 new cases and 416 deaths were recorded as the political tenor of the public health response has decisively shifted. St. Petersburg has followed Moscow’s lead, introducing limited restrictions on restaurant hours, canceling shared dining spaces at festivals and similar events, restricting the use of malls, and reducing max capacity for cinemas to 50% from 75% among several other measures. Sakhalin and Kemerovskaya oblast’ have launched mandatory vaccinations modeled roughly on the 60% requirement in Moscow and the surrounding region. Broad restrictions have been introduced in Kaliningrad, Nizhegorodskaya oblast’, Ivanovskaya oblast’, Karelia, Khabarovsk krai, Vologodskaya oblast’, and more. The Kremlin has clarified that there’s no ‘total’ vaccination campaign happening nationally in hopes of dodging any blame. As the Moscow Times’ Felix Light, Pjtor Sauer, and Jake Cordell fantastically reported, regional governments have turned to businesses in hopes of achieving vaccination progress in order to please the center:

Note that Russia’s actually behind the world average overall despite having leapt ahead to develop a vaccine as fast as possible. The current expectation is that the new scramble for vaccinations and restrictions will allow the new case load to peak by the end of June. That’s the hope, at least. You can sense the panic about how things are going.

Low hanging fruit or how I learned to stop worrying and love summitry

The summit between Biden and Putin yielded one substantive victory and a few symbolic ones for a more rational, calm relationship: respective ambassadors will return to their posts, the State Department and Ministry of Foreign Affairs will begin consultations regarding the closure and reopening of consulates and visa processing capacity, both governments will at least talk about cybersecurity and consider trying to establish agreed ‘red lines’ for cyberattacks, and there’ll be new nuclear arms control talks though we don’t have a date. All told, the meeting was about as successful as one could imagine given the political contexts in Moscow and Washington. Neither side conceded anything important, both sought dialogue, and both managed to slip in statements to the press to reassure or else focus on domestic audiences. Because we know that Putin’s messaging was for domestic consumption and a bit of pride dealing with foreign press, I think it’s more important to look at what Biden said:

Biden began his remarks by making the most important point — bilateral relations have to be stable and predictable. The common retort online and among the more hawkish members of the think tank world is that Putin and Moscow’s strategic community don’t do stable or predictable. Biden stressed again the need to cooperate on areas of mutual interest and, most importantly to my mind, stressed that US policy has to serve its interests. Criticizing violations of human rights, for instance, were pitched as a matter of interest. That’s a diplomatic language far closer to what Trump likely intended in his own incoherent way than he delivered, and one more effective at communicating the United States’ posture with Russia. But unlike the unilateral and often vicious tone the previous administration set, we can see Biden set a tone for the rest of his term and that of his successor should he not run again in 2024 and they win — be firm in reacting to threats and provocations, clear in the willingness to talk on matters of mutual interest and strategic stability, and comfortable asserting values and the protection of basic human rights as a core American interest. He summed up the intentions behind the G-7 summit and this meeting by saying:

“Over this last week, I believe, I hope the United States has shown the world we’re back standing with our allies. We rallied our fellow democracies to make concerted commitments to take on the biggest challenges our world faces. Now we’ve established a clear basis — there’s much more work ahead, I’m not suggesting any of this is done. We’ve gotten a lot of business done on this trip. And before I take your questions, I want to say one more thing. Folks, look. This is about how we move from here. I listened to a significant portion of what Putin’s press conference was. And as he pointed out, this is about practical, straight-forward, no nonsense decisions.”

Putin returned the respect afforded him despite the issues raised back home with Russian press, when he pointedly said that much of what the Russian press and even American press say about Biden is simply not true:

It’s funny to see because it’s truly not about guile in that moment. There needs to be some kind of tenor set by both parties to be able to negotiate, even if the prattle of ink and camera hounds matters relatively little for decisions of state on strategic matters. Politico has taken the line that Biden’s ‘success’ is a breath of fresh air for European governments happy to see the US cool down tensions with Moscow in hopes of doing business once again. That’s a decidedly Franco-German attitude, of course, and one that will be proven wrong swiftly by the extent to which the political economy of Russia’s relationship with Europe has changed since Crimea because of Russian foreign policy, the EU’s mishandling of the Ukraine crisis, its impotence in Syria and struggles in Libya, and the now accelerating energy transition.

The new ‘bridge to Europe’ is hydrogen, a dimension of SPIEF that yielded no concrete results but will be important in years to come. Last year’s hydrogen strategy open called for demand-side measures to accelerate adoption — that’ll be a problem for Russian exporters if they don’t get in at the ground floor while European firms figure out how to produce within the EU. Biden’s Department of Energy, led by former Michigan governor Jennifer Granholm, is setting the stage for a national offshore wind renaissance if states fall in line. These moving pieces are just as important as any space for Europe to engage Moscow since they’ll form the basis for a fair bit of future US-EU partnership. The trouble remains that it’s unclear what Europe can offer Russia so long as it’s committed to the current sanctions regime. Besides, the European Parliament has consistently become more and more vocally critical of Russian policy. Take Pew’s polling on European attitudes regarding US leadership, in this case trust for foreign leaders:

Politically, there’s no real cost to being tougher, especially since we’ve seen an expansion of known Russian intelligence activity intended to be disruptive in Europe proper. In short, stability and room to breathe doesn’t mean there’s any breakthrough to be had. Biden knows this. He wouldn’t have come out with the interests rhetoric and approach if he hadn’t recognized that gaining political goodwill in Europe on Russia was cheap since they lack the capacity to meaningful challenge the harder line the United States has taken and, in some cases, have come closer to embracing it openly. The hope that the West rediscovers its confidence is perhaps still misplaced given its systemic dysfunctions. It’s well-served in this regard by the dysfunctions its competitors also suffer from.

To my mind, the real masterstroke was the decision to invite Zelensky to the White House in July. Not only does that help him domestically, but it also sends a signal that the US will actually meet with other countries affected by bilateral efforts and offer something more substantive diplomatically to support them, even when conditions have to be set. I have a great many anxieties about Biden’s presidency, not least of which concern the midterms next year vs. the current state of the legislative agenda and the likelihood that Kamala Harris will run as his successor and struggle. But despite the glaring failures on climate and linking the energy transition to a coherent US strategy for Russia, there has been a level of competence at least orchestrating diplomatic maneuvers around this summit that’s been comforting to see. Despite delusions of European strategic autonomy, the last week has seen a renewed commitment to deepen coordination and cooperation between the EU and US on a policy agenda touching heavily on security and the securitization of economic policy. With time, maybe it will become clearer that Russia’s mobilization threat against Ukraine ended up driving the two sides of the Atlantic together faster than Moscow could have possibly anticipated — I personally think this overstates a variety of structural factors at play that have less to do with Russia policy specifically — but all told, the summit ended with Russia receiving more of the respect its leadership so frequently craves without gaining an inch in practical terms. I wager the opposite, in fact, since Biden’s managed to restore personal relationships that’ll matter a great deal for future issues in Europe. Boring summits are the best kind when it comes to two nuclear powers. Now to see how the Kremlin manages the home front over the next 3 months.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).