Top of the Pops

Since today’s Defender of the Fatherland Day, Russian news outlets are mostly silent and news broadly is slow. So it’s a bit of a grab bag of stories, mostly about Eurasia but with a bit on Russia in the news and analysis. To begin:

Yesterday, Belarusian president Aleksandr Lukashenka and Putin met in Sochi to continue the never-ending story of talk about economic integration and joint projects:

It’s important that Lukashenka calm any fears in Moscow that his political position is unstable after the explosion of protest activity against the regime last year. It’s clearly the case that he no longer has much space to try and play Moscow off against Europe or Beijing. Several days prior in a meeting with Grigoriy Rapota, head of the Union State (between Belarus and Russia), that Belarus and Russia were prepared to return to self-sufficiency and a planned economy such that western sanctions would have no effect. Lukashenka noted that self-sufficiency could be achieved in 3-5 years, though one has to wonder just how many times they can kick the can down the road on that promise. It’s a theme Lukashenka has been hitting since last year in an obvious response to the exhaustion of Belarus’ growth model, itself an outgrowth of Russia’s exhausted growth model. A reminder from VTimes last year that Belarus’ economic complexity fell after a brief peak from 2012-2013:

The oil tax maneuver in Russia increased the relative cost of feedstock for Belarus’ refined product exports, something now again subject to revision depending on how MinFin, Novak, and the oil sector negotiate over tax burdens. Higher fertilizer prices from the food demand and commodity price rally from last year into this year will help Belarus’ current account and stability, but will also see margins fall as oil prices rise. Plus it’s not like potash would save the economy if earnings rise for too long. It’d rather just further concentrate investment into a commodity sector. And the only reason Belarus’ economy is more complex than Russia’s is that subsidized energy import prices allow uncompetitive domestic manufacturers to stay afloat. The new round of credit borrowed from Moscow is worth $3-3.5 billion to boot. Lukashenka has always been masterful at getting what he wants and giving as little as possible in return. The protests and his response have rendered that impossible with Europe and his current gambit is to take as many doses of vaccines from China as possible to get Moscow to fork over Sputnik-V at a discount. He just received 100,000 reportedly for free, which usually means he promised Beijing a certain volume of a commodity export in return. Chinese policy entrepreneurs unable to hack it on priority markets are still going for small ball investments to curry favor, including a recent call to build 20 blocs of social housing. But Belarus’ China card relies on its agricultural sector, fertilizers or food production, and its control of the main railhead coming out of Russia into Eastern Europe for Eurasian transshipment. At this point, there’s little to see offering much of a growth impulse for Belarus’ economy so long as its neighbors — Russia and Eastern Europe — are slow to grow from structural stagnation, Europe’s deflationary policy bias, and imbalances within the Eurozone. Deeper integration into the Russian economy and its political structures seems inescapable (though it’s also seemed mostly inescapable for most of the last decade if you looked under the hood, to be fair). Belarus has effectively been a net recipient of financial transfers and rents from Russia’s regions and federal budget for decades now. Moscow has opened up bids for its procurement contracts to Belarus’ agricultural tech firms i.e. its tractor manufacturers. But those bids are more highly prized the more austere the budget is. Greater integration into Russia could bring Belarus into greater conflict with local interests in Russia, and that’s when the fun really starts.

Around the Horn

January data from TsIAN shows that prices for first-homes in new build apartments were (relatively) stagnant for the month, only rising 0.6% in Russia’s 16 biggest cities — however, that figure rises to 1.7% for the national average using data from firm Etazhi. On the one hand, it is good news for the housing price bubble that had visibly emerged by November. An increase in developer activity in Moscow and other large cities for new builds helped ease some of the pressure on the market. On the other hand, monthly price inflation for new builds in Moscow in January was still 1.8% per TsIAN’s more conservative data. For context, annualize that rate and you’d see a 23% increase for 2021 vs. a topline inflation rate nearer to 5% with a target of 4%. Monthly increases in the range of 0.2-0.5% fall comfortably within what macroeconomic policy is supposed to maintain and correspond to how developers seek to pass on costs. There hasn’t been a rush into new construction because the sector doesn’t yet know how the mortgage subsidy program will be unwound, which means that declining rates of price inflation suggest buyers are starting to reach the limits of what they can collectively afford. But if that’s the case and that happens without any major housing expansion, Russian consumers will be left holding the same bag their counterparts in the West have been for decades: price increases will stick since developers can’t deflate costs (especially with construction inputs rising in price due to the new commodity cycle) and systemic under-investment into new housing as well as a potential shift in buyer preferences because of the mortgage program will generate more pricing pressure on units in relation to underlying demand.

Russia’s MinTrud is looking to change the rules under which pensions are calculated and provided as well as expand the list of professions that have the right to early retirement in a move to account for COVID disruptions in labor law. MinTrud wants to include time spent learning skills or in educational programs while one’s job is being held for them into the time for which their pension pays them back as well as making sure that medical professionals, teachers, and public transport workers can retire early after an was an undoubtedly terrible year (and months ahead). Any time spent on temporary disability or on paid or annual leave are also factored into the length of service that is paid back from an individual’s and an employer’s contributions to the national Pension Fund. This is just a good policy at the moment, but what it’s really doing is expanding the number of people who, ideally having saved a little bit, can kick back early and live off of fixed incomes that are paid out by the state. Basically, these types of social policies expand the size of the political constituency that prefers deflation to inflation — fixed incomes are terrible during periods of higher inflation — and are also a useful campaign plank for September so as to cement support with anyone starting to consider retirement and expand the role of the state in maintaining living standards.

Georgian opposition figure Nikanor Melia, leader of the United National Movement Party founded by former president Mikhail Saakashvili, has finally been arrested after the party’s offices were stormed. The development comes after Tbilisi’s general prosecutor Irakli Shotadze announced Melia would be arrested on February 17, after which Melia simply refused to leave his party’s offices. Former Prime Minister Georgi Gakharia announced his resignation after the decision over the arrest was made as several hundred people gathered to surround the office to protect it from the police. Clashes for several days preceded today’s events. The standoff with officials began athe United National Movement and other opposition parties refused to join the parliament led by Georgian Dream due to the falsification of results from October 31 (despite international certification that the elections were fair). Bidina Ivanishvili, the billionaire godfather of Georgian politics, announced in early January he was leaving his post as party chairman of Georgian Dream and returning to private life, prompting massive speculation about what exactly is going on. What seems likeliest is that the opposition is so divided (aside from their parliamentary boycott) and Georgian Dream’s control of the country’s administrative resources so secure that there’s simply not a clear need for a public broker to keep what is effectively now a system led by a ruling party with a strong majority and coercive means to retain power going. Ivanishvili can retire to the shadows and still do as he pleases, but let the system run more of itself, not unlike the approach Putin took after returning to the presidency in 2012. Western governments will hem and haw, but track what’s happening with Georgia-China trade. The first direct train shipments from X’ian are now launching and any increase in trade and financial flows in the coming year between the two countries undermines the negotiating position for the EU and US to demand changes since Ivanishvili can now deny playing any role behind the scenes to undermine democracy. Shipping is not a major economic growth driver, but it creates rents. Rents can rent friends, especially since tourism — the national economic engine — will take longer to recover and China is Georgia’s biggest trade partner due to COVID.

Reporting yesterday from Chris Rickleton at Eurasianet offered a stark reminder of the gravity Beijing exerts in Central Asia: Kazakhstan is no longer a safe haven for Uighur refugees and critics of Chinese policies in Xinjiang. It’s a big shift in direction after the Interior Ministry offered temporary asylum to Uighur refugees last fall. The state’s shift from uneasy acceptance (while remaining circumspect in protecting Uighurs) to suppression parallels a broader problem that’s become much more acute with COVID and shifting regional dynamics. The traditional consensus around a so-called ‘multi-vector’ foreign policy — often a polite way of framing sales of political access and natural resources to a wider batch of foreign interests to make sure the Moscow, European capitals, Washington, and Beijing would all have lobbies for their interests — is increasingly challenged by antagonistic and adversarial relationships between the major external powers in Central Asia. At some point, you can’t sit on the fence and hedge. China is too big and too important to anger by taking a stand on Xinjiang, a dynamic deepened by its earlier recovery from COVID and dominant role as a global commodity consumer. At the same time, the share of non-residents holding Kazakh debt led by international investment banks has reached a record high — 11.45% — thanks to higher coupons than in developed economies. The longer that trend continues, the more pressure on Astana to keep the Chinese government happy for the sake of its current account to avoid scaring off the people increasingly helping to finance budget deficits. The issue is less salient now that oil prices have recovered, but a trend to follow because of Kazakhstan’s considerably smaller domestic financial capacity to raise debt than in, say, Russia.

COVID Status Report

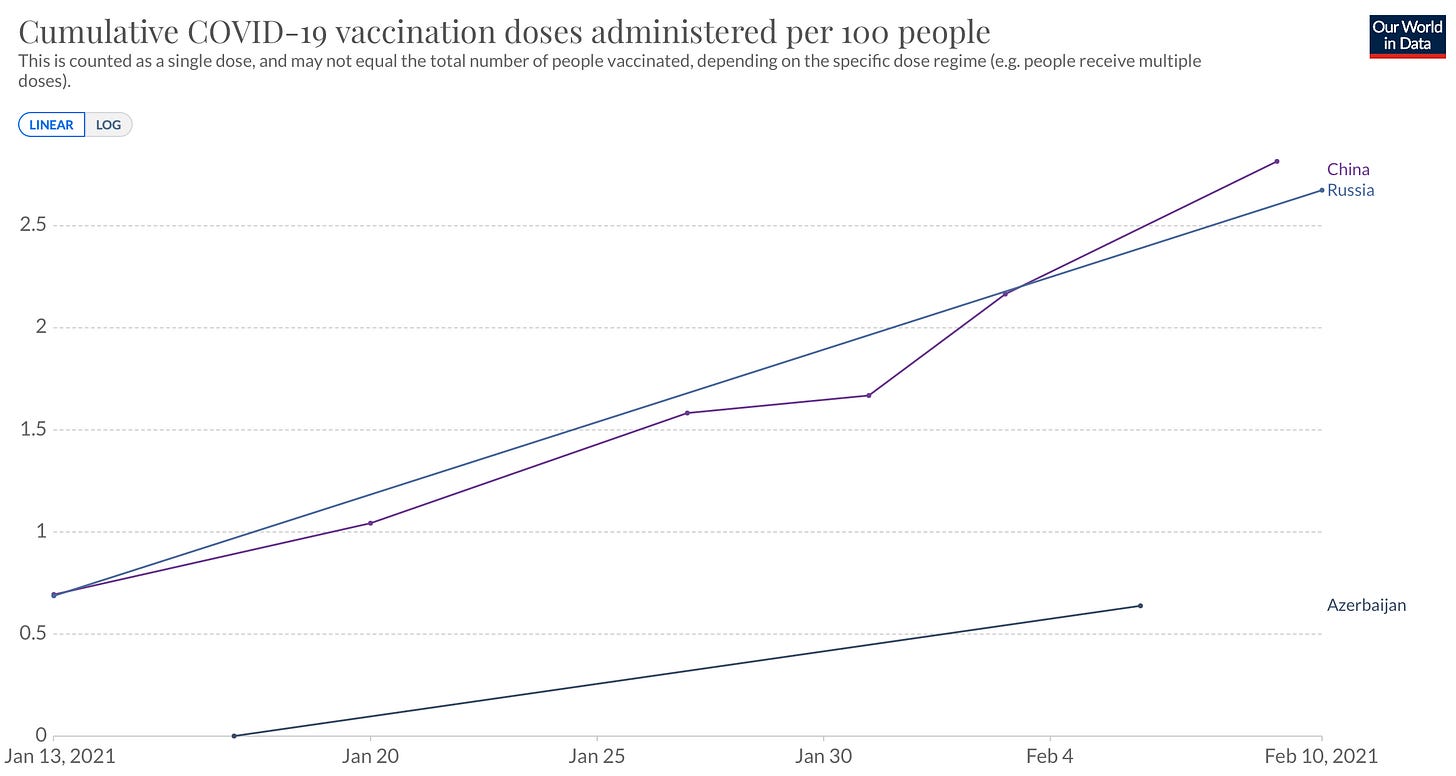

Unfortunately, Our World in Data only had Azerbaijan to compare against Russia and China available for vaccination rates, but it’s still worth an initial peek:

China’s vaccination efforts seem to be ready to ramp up past Russia’s by the time we get better data coming into March. Azerbaijan is obviously way behind, but had a lot of cash in hand to pay for imports of whatever Russia’s not using at home. The first doses of Sputnik-V produced in Karaganda in Kazakhstan are going out this week — a batch of 90,000 and thousands of medical professionals have already gotten vaccinated. Not too much yet, but it’s a good start to avoid import costs and improve the healthcare system’s capacity. Tashkent is touting a joint vaccine developed with Chinese partners that’s far more effective against the South African and Brazilian strains of COVID than Moderna, but there’s little word on how fast production can be ramped up while doses of Sputnik-V are bought. Ukraine has been stuck negotiating with NovaVax, Sinovac, and Pfizer after outright refusing Sputnik-V. Taking the 30,000 ft. view, it seems very likely that Russia will successfully unload a large share of its unused doses into the EAEU and CIS sans Ukraine before China can make too much of a dent for the simple reason that China doesn’t have a problem with domestic take-up of vaccines so far as I’ve seen and will prioritize itself since its economic recovery, though led by external demand for its production from last year, is really a matter of domestic consumption.

The Wages of Reconstruction

Vedomosti ran more coverage the last few days of Azerbaijan’s plans for the reconstruction of territory in Nagorno-Karabakh it won back in last year’s war. It’s going to be a long, arduous, and costly process that will weigh heavily on Azerbaijan’s finances, economic, and foreign policy outlook for the next decade. Initial cost estimates are greater than recorded GDP for 2019, but they’re immaterial in many respects. The actual costs are likelier to be higher, not lower, based on the development plans in place and realities of rent distribution in Azerbaijian. To start, Nazim Imanov — head of the National Academy of Sciences economic institute — indicated the following goals/realities: agriculture will be the main driver of growth in Karabakh, de-mining operations may take 10 years to make all arable land effectively usable, and Karabakh is intended to account for 20% of GDP without accounting for oil & gas. The expected spend on Karabakh this year amounts to $1.5 billion — about 3% of 2020 GDP. The Ministry of Finance’s projections for future growth, part of what they term ‘initial budget indicators’, are worth a look. This is all in billions of manat, which are effectively pegged at 1.7 manat to 1 USD:

Non-oil GDP growth — mostly tourism and low-value added agricultural production — will obviously outstrip anything on the oil & gas side, though this compositional breakdown is quite deceptive. The political economy of transitioning to a less O&G dependent economy doesn’t add up alongside the new expense of incorporating Karabakh. For instance, state subsidies are paid directly to farmers — now 1 manat per liter — to keep the cost of diesel fuel down, and therefore make agricultural output more competitive. While intended as a one-off measure, the state’s subsidizing initial investments into new agri-production to keep stuff afloat this year: lemon producers are being paid 11,000 manat per ton, oranges are getting 9,000/ton, pomegranates in less productive land are getting 5,000/ton, and so on. Flour producers are getting 35 manat/ton through May. Key foodstuffs have been stockpiled by state ministries and producers punished for “artificial price hikes” — same as it ever was with Russia’s approach too — at a time when food prices, in real terms, are breaking past where they were at the peak of the last commodity supercycle and closer to where they were in the immediate aftermath of the 73’ oil shock, when the global economy was much more energy intensive:

World Bank data estimates that subsidies and transfers accounted for 27.67% of spending expenses in 2019, a figure that would undoubtedly rise with the additional fiscal weight of Karabakh. Oil & gas are basically the only source of surplus rents to redistribute along those lines, and Baku faces a more acute version of the challenge Russia’s been stricken with: aggressive attempts to diversify away from hydrocarbon rent dependence almost always follow market crashes, the effect of which is to begin to expand the relative pool of economic actors, sectors, and/or classes who require subsidies or rent redistribution to become viable. But in this case, agriculture isn’t going to produce significant export volumes and is mostly for domestic consumption and low-level trade with neighbors save a larger possibility to sell to Turkey. So the non-oil GDP figures you see from the budget forecasting out of Baku reflect the durability of rents that can be redistributed from oil & gas. Hydrogen is another area that will grow in years to come, but seems unlikely to generate the same kind of rents as oil — a reality that’s already hit home since natural gas is similarly less profitable as a source of rents for the budget, if more efficient insofar as gas prices can subsidize industrial manufacturing and heating directly. The point being that Baku long missed its window to pull off the maneuver it’s now trying to.

Since the manat is dollar pegged, inflation only hit 2.8% for 2020, which undoubtedly helped with economic stability. But the inflation expectations for the US dollar are trending up a bit alongside the oil price recovery. PCE = personal consumption expenditures price index for inflation:

Since commodity prices overall are trending higher, the recovery in oil prices — which then stabilizes Azerbaijan’s budget — may well end up increasing subsidy expenditure to boost non-oil & gas sectors that consume the other commodity inputs whose prices are rising. And if oil prices fall again, noting that Azerbaijan will never again really raise output, the situation goes on and on and on until subsidized sectors can actually compete and succeed without budgetary support. The good news is that Azerbaijan’s external and domestic debt levels are quite low which, aided by the de facto dollar peg, means that there is considerable space to borrow externally in order to finance development in Karabakh. However, the development climb ahead is considerable even with more space to borrow. Virtually no foreign capital is involved in infrastructure in the country for the simple reason that owning it provides rents to the Aliyevs and their allies:

The result of this is that there’s no incentive to improve governance frameworks in practice, aside from the usual appeasement of multilateral organizations providing development loans, and that the cost of integrating Karabakh will be all the higher. There’s no crowding in effect that can take place. All of this means that the range of economic activities requiring budgetary support will only expand while Baku figures out how to finance development. The regime won a public coup winning the war. It’s not clear it can afford the peace without help from abroad.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).