Top of the Pops

Just when you thought the reportedly US-backed plot to overthrow Lukashenko couldn’t get any crazier, the US Treasury Department has announced the reimposition of 2015 sanctions on 9 state-owned Belarusian enterprises that collectively account for 20% of Belarus’ export earnings. Their imposition is predicated on human rights violations and political repression, which raises the question of why now assuming there wasn’t some long-running internal debate at Treasury. I’m not convinced that the Biden administration’s approach to Belarus reflects a particularly strong belief that sanctions have any impact on the human rights situation, but rather are aimed to disrupt the best-laid plans for Putin’s address tomorrow and continue the logic implied by a military withdrawal from Afghanistan. The following are taken from Belarus’ National Bank stats where I’ve calculated an ‘implied’ foreign income or transfer of income reflecting the gap between the recorded trade balance and current account operations listed, presumably explained mostly by transfer payments since Belarus’ foreign investments aren’t sizable enough to generate these figures:

The light green represents foreign income needed to explain the gap between the current account, shown by the line (stacking it would double count it and I preferred to break it out separately), and the trade balance. As we can see, since 2014 the implied level of transfer from Russia worth billions annually have increased irrespective of oil price or refined product price levels. These figures also understate them since export earnings for oil products are themselves generally subject to an effective discount on imports, allowing refiners to achieve better margins for exports while lowering domestic prices and also include transit fees. Biden’s team has identified the problem that both Lukashenko and Putin face whenever they pivot to deeper integration of the Union State — it’s costing Moscow more and more over time to maintain on top of the political unpopularity of deeper integration among younger Belarusians. By denying Belarus the ability to readily access export earnings, particularly from the Belneftekhim and Naftan refining firms, they’ve decided to find a new way to poke at Moscow while ostensibly standing up for the rights of Belarusians. Both Lukashenko and Putin have all the more reason to circle the wagons, but they’lll need to sort out what the final bill will be and who exactly is paying it.

What’s going on?

Rosatom’s hit a roadblock building a new nuclear-powered icebreaker as a result of a successful complaint to the Federal Anti-Monopoly Service (FAS) — Chinese shipbuilder Jiangsu Dajin appealed its exclusion from the competition for part of the contract. Atomflot is planning a counter-complaint to FAS, but everyone’s up against the project timeline. A wharf for construction is needed by fall 2024 and business negotiations for anything being built with a nuclear reactor understandably are high-stakes. Jiangsu Dajin submitted a bid to build a floating dock that came in under the maximum 5 billion rubles ($65.6 million) set as a parameter, not significantly more expensive than bids from Turkish firms Epic Denizcilik and Kyzey Star Shipyard, the former of which was also excluded. The issue, however, isn't the price point or even the firms involved. It’s another excuse to fight over import substitution measures. Not a single Russian shipbuilder was included in the original tender because none can build the same dock needed for less than 8.5 billion rubles ($111.52 million), a 70% price increase for the same project. The fear is that foreign contractors who require sub-contractors to fulfill the order — true for all the applicants to varying degrees — will take the advance up front and drag their feet on completing construction. It may well end up going to a foreign contractor. You get the sense that Kyzey is best positioned as the current policy process plays out. But the timeline requires action urgently, and that could end up benefiting those lobbying to throw more money at a Russian firm ultimately more accountable to diktats from Moscow.

The RSBI index measuring business attitudes shows that businesses have recovered to pre-COVID levels if not surpassed them — given that these are month-on-month measurements, they’re more indicative of a direction of travel than a relative level over a longer period of time. Following up on yesterday, it similarly reflects the extent to which firms are used to surviving in crisis conditions. Like a PMI, 50 indicates no change with values above indicating an improvement and below indicating worsening confidence/feelings about the state of things:

Dark Blue = services Red = retail/trade Light Blue = production

As we can see, production’s almost always been the most bullish, but dipped slightly in March while services logically benefit from the lower infection rates. Retail’s still ticking up, but if that figure drops in April, then my own suspicions about the strength of the consumer recovery are likelier to be confirmed (and conversely, need to be re-examined if not). Interestingly, only 33% of firms reported expecting a sales improvement for April. At the same time, investment activity declined in March. So what seems likelier is that we’re seeing the initial bump from operations normalizing, with production riding a 4Q budget-fueled tailwind, but without sustained confidence that the recovery has deep traction (yet). That may change after the next major data releases.

Following the Czech Republic’s expulsion of 18 diplomats after linking the GRU to a 2014 explosion at an arms depot and Russian response expelling 20 diplomats, Czech authorities are going after Rosatom’s export earnings. They’ve decided to ban Rosatom from participation in the upcoming tender to expand the Dukovany nuclear power plant. Consider that just 3 weeks ago, the government was clear that Rosatom is an important partner for the energy sector. It’s tempting to infer larger narratives from decisions that are clearly rooted in national political concerns rather than some grand structural change, but Rosatom’s exclusion is notable precisely because Rosatom has long been the most professionally and ably run state-owned energy firm for an obvious reason: you don’t screw around with nuclear power. The question is whether or European countries with tentative projects lined up that Rosatom is either pledged to take part in or else preparing to compete for follow suit. The company expects to receive an answer from the Hungarian government about the expansion of Paksh-2 in the fall, creating yet another avenue for Orban to win concessions fro Brussels if these issues rise to the level of the EU. I’m not holding my breath, however. Despite Rosatom’s massive export portfolio, it needs its European plants to deliver to make up for what are frequently minimally profitable terms on riskier markets like Egypt or Turkey, where credit subsidies and pricing agreements tend to undermine future returns. The Czech government didn’t just target Russia, though. It also excluded Chinese firms from the tender. Now to see how other NATO members react.

The combination of rising commodity prices and loss of migrant laborers to COVID restrictions are threatening Moscow’s existing infrastructure plans if we look at the Baikal-Amur Mainline (BAM). In 2019, 40 billion rubles ($525.6 million) were spent on labor. That rose to 70 billion rubles ($919.8 million) in 2020. MinStroi is scrambling to plug the gap left by migrants from Central Asia, Armenia, and China by pulling RZhD construction labor from the European part of Russia and using soldiers to pick up the slack. Adding rising equipment costs, the project appears to be 85-90 billion rubles ($1.12-1.18 billion) short as of now and last year, the labor shortfall was in the range of 4,000 people. The soldiers on loan from the military only account for 5% of all labor costs for the moment, but if the current agreement between RZhD and MinOborony is expanded, that figure could swell. The shortage of labor could increase labor costs by 70-100%, worsened by the poor logistics along the route. It’s already increased the cost of the second stage of the BAM modernization project by 40 billion rubles ($525.6 million). Metals prices have also shot up around 30%. Evraz holds a 5-year to supply BAM specifically, which has a built in clause holding down annual price increases to 2-3% per its formula. The overall lesson here is that infrastructure, already a startlingly under-served area of state spending and development plans, is now getting far more expensive because of the combined effects of the new commodity cycle, rising global growth, and loss of migrant labor. Because Moscow refused to spend bigger when commodity input inflation was lower and the labor market functioning more normally, it’s now trapped itself with a far steeper bill should it announce new initiatives tomorrow or later this year. Worst of all, the long-term supply contract model can’t hold prices forever as metals firms are losing profits that could support expansions of productive capacity, further worsening the domestic inflationary effect.

COVID Status Report

New cases came in at 8,164 with reported deaths at 379. We’ve finally seen an uptick in net cases (even if small) from the week-on-week data. Considering that the official data understates the case load and hospitalizations have begun to tick up in Moscow, it reinforces fears from the last 2 weeks about a third wave:

Russia’s PACE delegation has clearly stated the country’s opposition to COVID passports as part of any long-running recovery plan to help normalize travel. That flies in the face of a more complete normalization of the service sector given that Smol’ny’s inter-departmental council for anti-COVID activity in St. Petersburg is now briefing that the city’s caseload has never reached the minimum levels seen last summer and a 3rd wave is very, very likely. Add that Rospotrebnadzor is now seeing the development and spread of distinct Siberian and Northwestern strains of the virus and it’s not looking great in the months ahead.

You only give my your funny papers

Since the advent of the COVID crisis, Russia’s state banks have done a heroic job maintaining macroeconomic appearances while covering the state’s borrowing needs and administering crisis-measure loan programs. Their role is all the more impressive considering an interview that TASS of all outlets published with Kyle Shostak of Navigator Principal Investors who claims that based on their own experience and observations, roughly 2/3rds of Russia’s non-resident-owned sovereign debt is held by state banks. There’s clearly a methodological problem in parsing out the timeline of when this transformation takes place but let’s apply it to all non-resident debt as of last January to get a sense of what it really means:

The share of foreign-held sovereign debt is less than half of what the official data shows assuming that back of the napkin calculation on Shostak’s part is true — it’s crucial to acknowledge this is still somewhat speculative, but it fits with other information available. What’s more, the nominal increase in volume held by foreign investors that aren’t state-banks, assuming this breakdown is statically consistent between Jan. 1 2020 and March 1 2021, would be a measly 90 billion rubles vs. a total nominal increase of 4.9 trillion rubles. The narrative that OFZs are impervious to sanctions and geopolitical risks could reflect investors changing their positions, buying in and selling out rather but maintaining a healthy trade. However, at least per Shostak’s claim, it’s rather the case that Russia’s state-owned banks are projecting calm that actually would otherwise not be there. If we think about what’s happening in terms of the current and capital accounts as well as financial operations, state-owned banks are recycling their earnings, mostly in rubles, through foreign accounts and subsidiaries to maintain inflows for ruble stability while having the added benefit of financing the deficit.

This dynamic explains more readily why the Central Bank is worried about careless monetary expansion — banks are now requesting 300 billion rubles of liquidity via central bank operations to finance purchasing more sovereign debt, a potentially escalating loop without real foreign investor interest depending on how large the deficit goes (still lots of run to room I think, to be clear). That doesn't mean monetary inflation is going to take off given that demand returning to pre-COVID levels would still leave it weak. We’ll know more tomorrow what, if any, major social and infrastructure spending plans materialize. But effectively the Central Bank isn’t just printing money for domestic banks to cover the deficit, they’re providing the means to recycle rubles in a manner to meet macroeconomic stability mandates because of the institutional role of state banks. At the same time, Sber is increasingly convinced that the Central Bank will adopt a more aggressive than expected tightening of policy with a 50 basis point hike to 5.0%. That would signal a likely slowdown in the provision of liquidity to banks specifically to maintain bond purchases, and also runs up against the likely spending plans that should come out tomorrow. In a weird way, this mobilization of offshore/foreign financial operations — always a problem for roundtrip FDI via Cyprus, the Netherlands, or other offshore havens from Russian investors — can be classified as a rather creative piece of import substitution. If capital can’t be attracted from abroad, then create the liquidity domestically and recycle it.

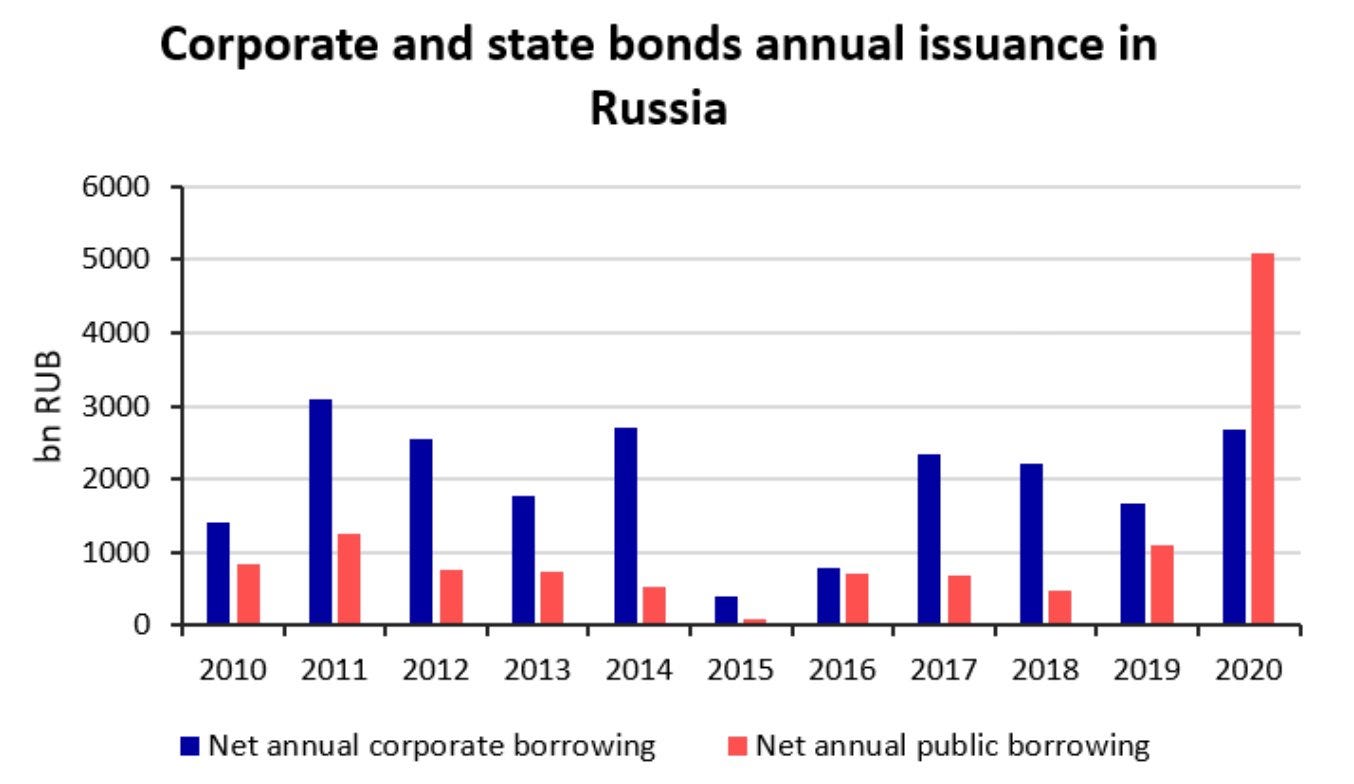

These efforts are reinforced by the role of SOEs, first mobilized late September last year to surrender hard currency earnings to cover banking sector liquidity needs, who deployed their 7-year high currency reserves from late March to purchase rubles on the forex market. The ruble hasn’t escaped the influence of the oil price or geopolitical risks, rather dollar and euro earnings from Russian firms even in a reduced price environment can be used to prevent contagion. They won’t stop the overall movement of the currency, but they can cushion it and prevent a larger run, particularly since their costs are in rubles so they lose relatively little changing the currency out unless they’re forced to borrow abroad to finance future operations. There’s some risk of that given the current OFZ purchasing program:

The crowding out argument isn’t particularly appealing to me because the volume of credit available that’s been created in the last year is quite large. More salient is the issue of why companies need to borrow in the first place and effects of a weaker demand recovery on corporate earnings, the latter of which benefits from public borrowing if money is converted into stimulus and investment of various kinds. Foreign borrowing has been a relatively small source of investment financing for Russia over the last 20 years, so it’s really Eurobond issuances that matter when it comes to foreign firms accessing foreign capital markets for business operations. But these theatrics do very little for real economic activity in the form of growth or intermediate demand even if they help maintain macro stability.

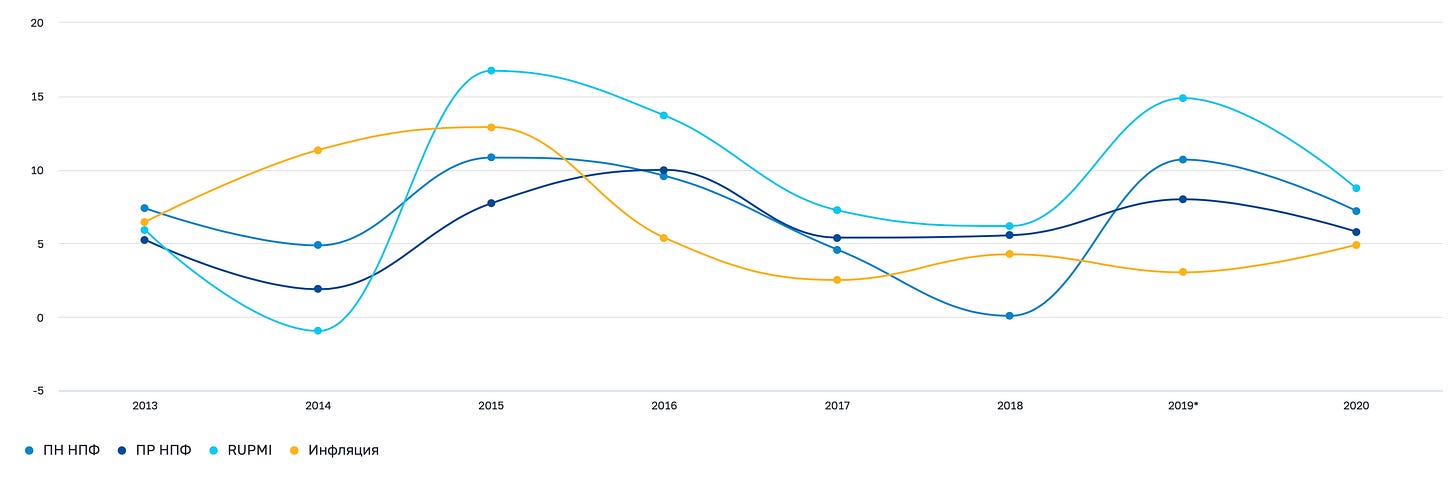

A new report from the Higher School of Economics forecasts 15 years of stagnation ahead, driven by the cumulative effects of demography, inefficient policy, import substitution, and falling oil & gas demand. The forecasted average growth rate for GDP is 1.4-1.8%, which based on the structure of the Russian economy will lead to further real income decline. Import substitution is a huge part of this conundrum. The act of substituting imported goods produced more efficiently and at higher quality levels abroad on markets where labor is more abundant or automation more feasible induces domestic cost inflation at the same time SOEs, the Central Bank, and MinFin figure out new ways of holding the system together. What’s worse is that as the labor force declines in size and the adoption of automation is likely to be slower in Russia due to inadequate investment levels and, with the renewed hawkish turn at the Central Bank, rising costs of credit, the only way to secure adequate labor is to pay higher salaries. This cycle then encourages productivity-enhancing business investment that would lead to some unemployment in key sectors and challenge the traditional political model of employment and stability over growth. These pressures then play into the Central Bank’s fears of inflation run amok and incentivize further tightening or, from MinFin, renewed efforts to increase the non-oil & gas tax burden in order to insulate the economy from commodity price cycles. The loss of foreign investors’ faith is a problem, yes, and one much greater than advertised. There’s a related problem from all this chicanery that gets less attention — maintaining pension fund returns which could otherwise be eaten alive by inflation:

Yellow is the annual inflation level vs. several pension funds annual returns. As returns fall with lower interest rates and inflation picks up, that hits retirees and those close to retirement, one of the most important political blocs for the regime. Yet higher interest rates intended to quash inflation end up weakening the real economy recovery, hurting younger Russians who just need well-paying jobs and the ability to consume to be able to maintain the best-laid import substitution plans and afford the structurally rising tax burden. It’s a generational time bomb. The loss of foreign investors is a problem because state banks are the ones filling the gap, not because the deficit can’t be financed. This will inevitably alter policy lobbying dynamics in Moscow and likely strengthen the relative interest in maintaining a deflationary economic policy environment in order to increase the profitability of the banks recycling their earnings to maintain the balance of capital flows and bond purchases, unless there’s a newfound consensus we aren’t aware of that Mishustin has managed to strike. As the cumulative inflationary effects of rising commodity prices, import substitution, and labor shortages crash into the continuing neoliberal policy framework, you get an economy that becomes simultaneously more state-dominated every month and less structured to serve the economic needs of Russians under the age of, say, 45. Rates are likelier to go up to maintain returns for the old at the expense of the young without a shift in fiscal policy. Unless they arrest income decline, there’s a huge bloc of Russians who have to wonder why they never get money for the trouble they’re being put through.

Like what you read? Pass it around to your friends! If anyone you know is a student or professor and is interested, hit me up at @ntrickett16 on Twitter or email me at nbtrickett@gmail.com and I’ll forward a link for an academic discount (edu accounts only!).